Tribute to Lenora Lapidus

Introduction

On May 5, 2019, contributor Lenora Lapidus passed away after a long fight with breast cancer. As director of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project, Lapidus dedicated her career to fighting for gender equality. She pursued an expansive vision of civil rights for women of all ages and backgrounds. Her work challenged educational inequity, economic injustice, gender-based violence, and mistreatment of women in the criminal justice system.

In recognition of her decades of advocacy for women’s rights, we dedicate this special symposium issue of The Harbinger to Lapidus and include the following tributes in her honor. The issue includes an article by Lapidus on Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s early career, the final line of which applies equally to the author herself: “We are deeply indebted to her for her work laying the bedrock for gender equality, and we are proud to follow in her footsteps to expand upon this foundation.”

From the ACLU Women's Rights Project

Lenora M. Lapidus, who for nearly two decades led the women’s rights program at the American Civil Liberties Union once helmed by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, died on May 5, 2019, of cancer. She was 55.

Ms. Lapidus’s career as an advocate for women and girls spanned three decades, most of it spent with the ACLU. It began in the summer of 1988, when Ms. Lapidus was a law student intern with the organization’s Women’s Rights Project (WRP). Co-founded in 1971 by now-Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg, WRP had won numerous landmark Supreme Court rulings throughout the 1970s that established women’s rights under the U.S. Constitution. Twelve years after her internship, in 2001, Ms. Lapidus returned to WRP as its Director, having already served as the top lawyer with the ACLU’s New Jersey affiliate.

By the time Ms. Lapidus took over, WRP had ceased active litigation, but she revived it and grew it to nearly a dozen staff members, pursuing an ambitious litigation and policy agenda targeting a broad range of economic and social justice issues that yielded victories in the Supreme Court, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and countless federal, state, and local courts and legislatures. At the ACLU, we are fond of saying that Lenora Lapidus renovated the house that Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg built.

Early in her tenure, Ms. Lapidus saw the potential of using an international human rights approach to address gender-based violence. In 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected the civil rights claim brought by Jessica Gonzales against Colorado police for failing to intervene when her estranged husband abducted her three children, who later were killed. Ms. Lapidus and WRP took up Ms. Gonzales’s cause before the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR), a body charged with protecting human rights throughout the western hemisphere. In 2011, after six years of litigation, WRP won a decision from the IACHR recognizing, for the first time, that failure by the police and federal courts to protect victims of domestic violence is a human rights violation. Although the U.S. refused to recognize the IACHR ruling on technical grounds, Ms. Lapidus and her WRP team used the decision – profiled in a 2018 documentary, “Home Truth” – to win implementation of measures to increase government accountability to domestic violence survivors, including, in 2015, a U.S. Department of Justice guidance detailing the police response necessary to comply with civil rights laws. Today, more than 30 local jurisdictions have adopted resolutions recognizing freedom from domestic violence as a human right.

Ms. Lapidus’s ability to see links and connections between social justice problems was reflected in her deeply structural approach to attaining gender justice. WRP under Ms. Lapidus prioritized the housing rights of domestic violence survivors, given that abuse is a leading cause of homelessness among women and their families. To that end, WRP has brought groundbreaking litigation challenging local “nuisance laws” that call for eviction of individuals who repeatedly call the police to their homes, with the effect of disproportionately punishing domestic violence survivors for seeking protection from abuse. In response, courts have found these ordinances to be unconstitutional, states have passed laws protecting the rights of residents to seek emergency assistance, and the federal government has said they violate anti-discrimination guarantees.

Ms. Lapidus recognized that women’s workplace equality had farthest to go in two distinct areas: higher-paying, traditionally male-dominated fields, and lower-wage, female-dominated jobs. In the former category, early in her tenure Ms. Lapidus and WRP intervened in a lawsuit brought by the U.S. Department of Justice against the New York City Department of Education alleging widespread discrimination against female, Black, Latino, and Asian-American custodians. DOJ reached a settlement in the case that would benefit those groups, but when a group of white male custodians challenged those terms in 2002, the department – by then under the leadership of Attorney General John Ashcroft – reneged on its promise to defend them. WRP took over the representation of 25 of the women and custodians of color, and after a win before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, in 2013 reached a settlement with the city Department of Education that safeguarded its clients’ jobs.

Ms. Lapidus also led WRP in challenging one of the few remaining examples of express, formal sex discrimination: the U.S. military’s ban on women serving in combat roles. Within months of the ACLU’s 2012 lawsuit alleging that the ban violated women’s constitutional right to equal protection, then-Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta announced the end of the ban. (Because certain Army and Marine policies are nonetheless still impeding women’s integration into formerly-closed roles, WRP continues to pursue the lawsuit on behalf of the Service Women’s Action Network.)

To address the vulnerability of low-wage workers, Ms. Lapidus and WRP prioritized the interests of immigrant women of color. In 2007, WRP (along with ACLU’s Human Rights Program) sued the State of Kuwait, a Kuwaiti diplomat, and the diplomat’s wife for trafficking three Indian women and forcing them to work as domestic employees under slavery-like conditions. The case prompted a criminal investigation by DOJ – resulting in the diplomat and his family being forced to return to Kuwait – and obtained a settlement in 2012 that was the impetus for the adoption of a series of reforms by the State Department for immigrant domestic workers in diplomats’ homes, many of which were enacted into law in the federal Trafficking Victims Protection Act. WRP under Ms. Lapidus also undertook public education campaigns on both coasts to inform farmworkers, food processing plant workers, and nail salon workers about their rights under anti-discrimination, wage and hour, and occupational health and safety laws. Recently, Ms. Lapidus was part of the successful challenge invalidating then-Attorney General Sessions’ policy of denying asylum claims submitted by domestic violence and gang violence victims.

Ms. Lapidus’s expansive vision for women’s rights was legendary. Under Ms. Lapidus’s leadership, WRP entered legal territory not traditionally occupied by gender justice groups. In 2013, it secured a unanimous ruling in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, a landmark challenge to the patenting of human genes linked to hereditary risk for breast and ovarian cancers. According to NIH Director Francis Collins, “The decision represents a victory for all those eagerly awaiting more individualized, gene-based approaches to medical care.” The Court’s ruling assured that genetic testing that could benefit millions would not be impeded by corporate ownership of selected genes.

Ms. Lapidus’s alertness to the discrimination enabled by new technologies also resulted in one of her last cases, brought by WRP and private counsel against Facebook for permitting employers to target job advertisements to users by gender. Ms. Lapidus decried the “21st Century Discrimination,” as she termed it, that in effect revived the “help wanted – men” and “help wanted – women” advertisements of decades past. In April, the ACLU announced a landmark settlement with Facebook agreeing to alter its practices and halt discriminatory targeting for job, housing, and credit ads.

Ms. Lapidus waged the fight against pregnancy discrimination throughout her WRP tenure, including leading the strategy for “friends of the court” in filing briefs in the U.S. Supreme Court in support of Peggy Young, a United Parcel Service driver forced to go on unpaid leave when she had a lifting restriction during her pregnancy, even though other employees with similar limitations were offered desk jobs and other accommodations. In 2015, the Court affirmed pregnant workers’ right to accommodation. She also submitted comments to the EEOC on its Enforcement Guidance on Pregnancy Discrimination and Related Issues, and to the OFCCP on its Sex Discrimination Guidelines for Federal Contractors and Subcontractors.

Ms. Lapidus was a founding Steering/Advisory Board Member of the Equal Pay Today! campaign, a collaboration among national, regional, state, and local women’s rights and worker’s rights organizations formed to address the gender wage gap through policy reform, strategic litigation, communications, and mobilization of millennials, people of color, and other activists who care about gender equality.

Other forms of workplace bias that Ms. Lapidus tackled include the entertainment industry’s systemic failures to hire female directors – a cause that prompted a widely-publicized letter to federal law enforcement authorities and triggered an ongoing investigation by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission – as well as sexual harassment. An active participant in the Time’s Up organization, Ms. Lapidus recently joined congressional leaders and other advocates on Capitol Hill for the introduction of the BE HEARD Act, which would codify sexual harassment as a civil rights violation.

Ms. Lapidus long cited as inspiration Justice Ginsburg’s commitment, as a WRP litigator, to dismantling sex stereotypes not only on the job or in the classroom, but also at home. On a recent episode of the ACLU podcast, “At Liberty,” Ms. Lapidus reminisced about meeting with Justice Ginsburg before assuming the mantle of WRP Director, and asking her what she considered the greatest modern challenges for gender justice. Justice Ginsburg observed to her that while women had broken many barriers in the workplace, men had not yet broken those barriers in the home. In keeping with that mission, Ms. Lapidus’s team recently sued J.P. Morgan Chase to challenge as sex discrimination its presumption that only birth mothers could serve as primary caregivers for purposes of enjoying full parental leave benefits, a disparity rooted in time-worn notions of who is, and is not, the primary caregiver in families.

Ms. Lapidus taught courses in Gender and the Law, Reproductive Rights, Constitutional Litigation, and Women and Public Policy, as an adjunct professor at Seton Hall Law School, Rutgers Law School, and Rutgers University. She is the lead author of The Rights of Women (4th ed.) NYU Press, (2009), and has written book chapters and law review articles on a range of topics. She served in numerous board and advisory roles, including for the Global Justice Center, Women’s Forum of New York, Human Rights Watch Women’s Rights Division, Association for Women’s Rights in Development, and the New York Women’s Foundation.

Ms. Lapidus was recognized for her leadership on many occasions, including receiving a Wasserstein Fellowship from Harvard Law School for outstanding public interest contributions, the Trailblazers Award from Women and Hollywood, and the Lifetime Achievement Award from Pathways to Peace. In 2017, Women’s eNews listed her one of their “21 Leaders for the 21stCentury.”

Prior to becoming Director of the ACLU Women’s Rights Project in 2001, Ms. Lapidus served as Legal Director of the ACLU of New Jersey, held the John J. Gibbons Fellowship in Public Interest and Constitutional Law at Gibbons Law Firm, was a fellow at the Center for Reproductive Rights, and clerked for the Honorable Richard Owen in the U.S. District Court for the SDNY. She graduated cum laudefrom Harvard Law School and summa cum laudefrom Cornell University.

Ms. Lapidus was defined by her fierce tenacity, her generosity of spirit, her boundless optimism, her joy in life, and her commitment to her family. She was someone who demanded freedom and justice, and she was a force to be reckoned with. She cared deeply about mentorship, and about fostering the next generation of feminist attorneys and activists. She provided invaluable support, training, and mentorship to a host of young women lawyers and to the staff at ACLU. We will miss her terribly. But having learned from her, and continuing to be inspired by her indomitable spirit, we are even more committed to building on her legacy.

From Claudia Flores and Caroline Bettinger-Lopez

Back in the early 2000s, we both started as Skadden Fellows in the Women’s Rights Project (WRP) of the ACLU. Lenora had become WRP’s director a few years earlier and was rapidly growing the program, building on the legacy of WRP’s co-founder, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Lenora brought a fresh vision for gender justice to WRP’s work. At the time, the ACLU had just established an innovative program intended to incorporate international human rights law and advocacy into the organization’s civil rights and civil liberties work, the ACLU Human Rights Program. This approach was an expansion of the ACLU’s traditional work and still not well-accepted by most. But Lenora was one of the first project directors at the ACLU to embrace this form of advocacy as an avenue for relief for individuals whom the U.S. legal system had failed. She understood the potential of the human rights framework for women, especially for poor, marginalized women who were often excluded, in practice, from legal protection.

As new lawyers, Lenora urged us to be creative in how we sought justice for the women we represented. She helped us to frame gender-based violence as a form of gender discrimination and inequality, and as a pervasive societal structural problem. She encouraged us to access and apply new tools, such as human rights principles, to lay out a more substantive vision of equality than our constitution contemplated, one in which women were equal in all aspects of social, political and personal life.

Lenora also saw, before most, the importance of focusing on social and economic rights in advancing women’s equality. This, again, was a concept in international human rights law that was not well accepted by civil rights advocates here in the U.S. Under Lenora’s leadership, WRP focused on low-wage immigrant women workers, with the understanding that women’s equality would only be achieved if the most vulnerable and disenfranchised women had access to that equality.

In our first two years as lawyers, and with Lenora’s support and guidance, we advocated on women’s human rights issues that would define our careers in the long term. We advocated for a domestic violence survivor, Jessica Lenahan, who was told by the U.S. Supreme Court that she had no right to expect enforcement of her restraining order when her three children were tragically killed after being kidnapped by their father. We advocated for immigrant women who worked low-wage jobs as domestic workers and had been told by the U.S. government they had no rights because they were employed by diplomats. We advocated for undocumented women workers who took jobs no other Americans wanted, but were then too terrified to seek the wages they were due or report sexual harassment from their employers. Many viewed these as lost cases, but Lenora would not let them go. When all domestic avenues had been exhausted, we took these cases to international human rights fora and sought justice through policy change.

Lenora was truly a force of nature. She was a tenacious advocate—ambitious and indefatigable. Her clients and the lawyers she mentored knew that she would think through a problem until she found a solution. There was simply no other way.

Today both of us are clinical law professors and directors of human rights clinics tasked with training the next generation of women’s rights and human rights lawyers. We use much of what we learned from Lenora when we construct our dockets, when we identify forums for realizing justice for our clients, and when we structure our classrooms. We push our students to challenge themselves and each other in considering the law’s possibilities and limitations, and we ask them to think creatively and with vision. And most importantly, to not take no for an answer. Lenora was able to imagine a better, more just, world and we hope, in our small way, that we are carrying forward her vision.∞

From Helen Hershkoff, Joined by Sylvia A. Law

The Arthur Garfield Hays Civil Liberties Program at New York University Law School mourns the death of Lenora Lapidus. Lenora brought uncommon qualities of intelligence, strategy, and empathy to the ACLU and to her work on behalf of gender equality. Through her energy and enthusiasm, Lenora helped make the Women’s Rights Project more inclusive and inter-sectional in its approach; she also added warmth and kindness. Not surprisingly, Hays Fellows over the years enthusiastically sought placements, fellowships, and legal positions at WRP under Lenora’s leadership, and Lenora was a wise, dedicated, and gracious mentor. In addition to building the project, litigating cases, influencing legislation, and surfacing long-ignored issues, Lenora nurtured a new generation of feminist leaders whose understanding of equality was shaped and influenced by her deep appreciation of the relation among gender, race, and economic status. Lenora’s legacy includes:

Anjana Samant, 2001, now a senior staff attorney at WRP after fifteen years of intersectional justice work involving such issues as employment discrimination, sexual harassment, and reproductive choice.

Caroline M. Flintoft, 2002, who did her Hays placement at WRP, focusing on pregnancy discrimination and gender equality in community athletics. For eleven years Carrie worked at the International Crisis Group, doing everything from war crimes research (including sexual violence), to serving as in-house counsel, and most recently was a senior adviser on the humanitarian dimensions of armed conflict.

Sandra Park, 2002, a senior staff attorney at WRP, who, among other cutting-edge lawsuits, was counsel on the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court challenge to human gene patents.

Julie B. Ehrlich, 2008, who was a WRP Fellow after graduation, went on to be Executive Director of the Birnbaum Women’s Leadership Network at NYU Law, and now is Program Advisor & Chief of Staff at the Mellon Foundation (Office of the President).

Joanna C. Laine, 2015, who did her Hays placement at WRP, focusing on the housing rights of domestic violence survivors, and now works as a housing lawyer with The Legal Aid Society.

Courtney T. Weisman, 2016, who did her Hays placement at WRP, focusing on the then-anticipated Department of Justice guidance on sexual assault and domestic violence, and now is an election-law lawyer with Perkins Coie.

And most recently, Devika M. Balaram, 2019, who completed her Hays placement at WRP this academic year. In an email, Devika told me that throughout her placement, Lenora—despite battling with the cancer that took her life—“never missed a staff meeting, was readily available always, and came to work each day to fight the good fight.”

I first heard of Lenora when she was a summer intern at WRP and I was an associate legal director in the ACLU National Office. It was a joy to work with Lenora and to see her become an even fiercer advocate, a visionary leader, and a guiding light for women everywhere. Her death, too early, is a terrible loss and brutally sad.1

From Melissa Murray

I first met Lenora Lapidus almost twenty years ago, when I was a first-year law student. A group of female professors at Yale Law School had convened a conference on the status of women’s rights in the United States and around the world.2 Even in the early 2000s, the prospect of a conference hosted by one of the country’s preeminent law schools and devoted exclusively to the subject of women’s rights was something of a novelty. The conference attendees were a testament to the conference’s lofty mission and global focus. It was a remarkable group—leading scholars of women’s rights and gender justice, grassroots activists, judges, policymakers, and advocates from the leading civil rights organizations. For a law student, it was heady stuff to rub shoulders with the women who had literally made it their business to transform the global legal landscape into a more hospitable place for women and girls. The atmosphere seemed pregnant with passion, possibility, and promise.

Even among this group of luminaries, Lenora Lapidus stood out. The conference took place a year before she was appointed to head the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project (WRP).3 At the time, she was heading the ACLU’s New Jersey affiliate.4 But even then, a year before she would move into “the house that Ruth built,”5 her remarks—both in her formal presentation and in her questions to other panelists and attendees—provided a glimpse of the broad topics and expansive vision of women’s rights that would occupy her during her tenure at the WRP. A significant portion of the conference discussion involved critiques of second-wave feminism and the women’s rights movement. I do not remember if Lenora joined this chorus, but I do remember that her remarks focused on the urgent need to expand the fight for women’s rights beyond the traditional confines of abortion and birth control and to include a wider array of women.

As she envisioned it, the fight for women’s rights necessarily encompassed gender-based violence, sex trafficking, the combat exclusion rule, equal pay, and work protections for all workers. Today, this panoply of issues seems unobjectionable as part of a women’s rights agenda. But in the late 1990s and early 2000s, these causes were not always part of the stable of issues with which women’s rights groups concerned themselves. This was Lenora’s genius. As the leader of the WRP, she seized the moment when many viewed traditional feminism as failed or failing and she translated it into a vernacular that could serve a broader array of women and issues.

Under her leadership, the WRP remained its roots in fighting for gender equality, but it took the fight to new arenas. Moving beyond the traditional litigation paradigm, the WRP launched campaigns to inform farmworkers, food processing plant workers and nail salon workers about their rights under both occupational health and safety laws and anti-discrimination laws.6 In a similar vein, she challenged local housing ordinances that penalized survivors of domestic violence and abuse.7 As she made clear, these issues—workers’ rights and safety, housing security, and domestic violence—were integral to women’s economic security and equal citizenship, and as such, were as much a part of a women’s rights agenda as Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s cases on behalf of professional women and men.

Lenora’s vision of women’s rights was expansive both in the individuals it encompassed and the scope and nature of the work it entailed. Finding an inhospitable climate for domestic violence in the U.S. legal system,8 she joined other groups to challenge the U.S. response to domestic violence in international tribunals, securing a victory for Jessica Lenahan-Gonzales, a survivor of domestic violence,9 at the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights.10

As technology drove innovation, the WRP identified new ways that technology could also be used to entrench gender-based inequalities. Notably, despite considerable debate within the organization, Lenora, among others, urged the ACLU to join a legal challenge against Myriad Genetics, a biotech company that had developed a test for gene mutations that could indicate a heightened risk of breast and ovarian cancer.11 Because it held the patent to the technology, Myriad was able to monopolize testing, stifling research, inflating the cost of the test, and in the process, preventing many women from being tested. The WRP, alongside various medical groups, litigated the case all the way to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that human genetic material could not be patented.12 The Supreme Court agreed, ruling unanimously that, unlike synthetically-created genes, human genes could not be patented.13

The challenge to Myriad Genetics was just one of the “21st century cases” that Lenora pursued as director of the WRP. More recently, the WRP took on social media giant Facebook, arguing that its algorithms enabled employers to engage in sex discrimination in help-wanted ads.14 Just this year, the case settled, with Facebook agreeing to end the use of targeted ads.15

Lenora helmed the WRP for 18 years—a relatively short period of time. Still, even in this relatively brief period, she made an indelible impact. As ACLU director Anthony Romero acknowledges, during her tenure, she “renovated the house that Ruth built,” updating it for a technological age and expanding it to accommodate a more intersectional and inclusive vision of women’s rights.

Lenora never wavered from this expansive vision of women’s rights. And indeed, that is what stands out to me as I reflect on that conference, almost twenty years ago, when I first encountered her. In her remarks, she laid out a clear vision for women’s rights—one that that inspired a generation of young lawyers, who, like me, yearned for a more inclusive feminism. And she spent the rest of her life making that vision a reality. For all women.16

From the Brennan Center for Justice

The long fight for gender equality has lost a fierce champion with the passing of Lenora Lapidus. As Director of the ACLU’s Women’s Rights Project for nearly two decades, Lenora crafted a distinctive legacy: A litigator, an educator, an author, and an advocate, Lenora worked tirelessly to improve the lives of women across the country — and the country itself.

We at the Brennan Center for Justice had the good fortune to work closely with Lenora on our November 2018 convening on the Equal Rights Amendment, benefiting from her wisdom and insight. We take solace in knowing that the ongoing fight for the ERA has been enriched through her life’s work. Lenora’s absence will be felt throughout the community of those flighting for gender justice and equality, but we know that her passion will live on through the generations of dedicated advocates she inspired. Our heartfelt condolences go out to Lenora’s family, friends, and colleagues at the ACLU.

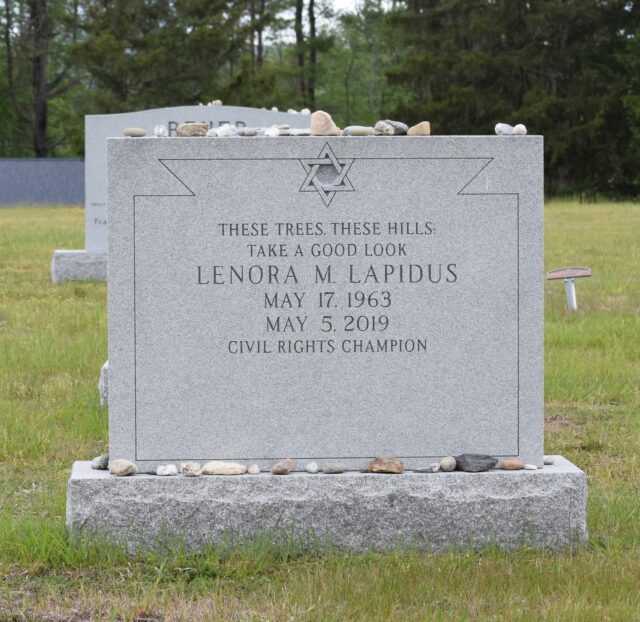

Photograph of Ms. Lapidus’s gravestone provided by Joseph Sefter.

Suggested Reading

Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the Development of Gender Equality Jurisprudence under the Fourteenth Amendment

"At the ACLU today, we are fighting to ensure workplace fairness, including protections against pregnancy discrimination and sexual harassment. We also seek to end gender-based violence in a range of contexts, including discrimination against survivors in housing, in

Book Excerpt: Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Irin Carmon ∞ & Shana Knizhnik ∞∞ This is an excerpt from the new book by Irin Carmon and Shana Knizhnik, “Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” In this excerpt, the authors begin their account with Struck, a

The Equal Rights Amendment: A Century in the Making Symposium Foreword

Regardless of the obstacles to ratification that remain, the renewed push for ratification makes clear that interest in the ERA is not merely academic or historical, but rather an urgent and necessary response to the many threats to women’s rights

Time for the Equal Rights Amendment

"As a matter of principle, amending the Constitution to include sex equality as a fundamental human right will send a clear public message that women are no longer to be treated as second-class citizens."