BDSM and Sexual Assault in the Rules of Evidence: A Proposal

Introduction

John E. Ludwig∞

Abstract

Propensity evidence has long been generally inadmissible, but in 1994, Rule 413 was enacted to admit evidence of prior “sexual assaults” committed by a defendant in a current sexual assault case for any purpose. Rule 413(d) contains several different definitions of “sexual assault,” or certain “crime[s] under federal or state law,” including (4): “deriving sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting death, bodily injury, or physical pain on another person.” Unlike other enumerated definitions, the definition in subsection (4) is the only one that does not contain a “non-consent” qualifier, meaning that even consensual sexual activities can be “crimes” under the Rule. Despite the lack of scholarly attention to this issue, the constraints on judicial discretion to preclude such evidence, combined with the particularly prejudicial nature of sexual act evidence, can have devastating and unintended effects on civil and criminal defendants.

Here, I propose a simple amendment to Rule 413 that makes clear that a “sexual assault” is only an act performed without consent, and provides an appropriate definition of “consent” in a newly-added subsection (e). I also critique the underlying proposition—that prior BDSM acts are relevant or probative of propensity to commit sexual assault—thereby undercutting any rational justification for the rule as presently written.

I. Introduction

James is on trial in federal court for sexual assault.1 The prosecution notifies James2 that when James takes the stand, the prosecution intends to cross-examine him about his sadomasochistic sexual proclivities.3 James’s lawyer moves in limine to preclude on three grounds: 1) this is inadmissible prior act evidence under Federal Rule of Evidence 404(b); 2) it is irrelevant under Rules 401 and 402; and 3) any possible probative value is vastly outweighed by the possibility of unfair prejudice to the defendant, demanding exclusion under Rule 403. Is the evidence admissible?

The answer, like all lawyerly answers, is “it depends.” Evidence of a person’s character or prior bad acts has long been inadmissible to prove propensity or disposition,4 but in 1994, Congress enacted several amendments to the Federal Rules of Evidence applicable in sexual assault cases.5 For example, Rule 413 created an exception to Rule 404(b), to admit evidence of prior “sexual assaults” committed by a defendant in a current sexual assault case for any purpose.6 Rule 413(d) then defines sexual assault by reference to certain “crime[s] under federal or state law,”7 including (4): “deriving sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting death, bodily injury, or physical pain on another person.”8

There is no shortage of criticism of Rule 413.9 The Rule was enacted in 1994 over near-universal objection by commentators, as well as by academics and practitioners on the Advisory Committee.10 However, no sustained scholarly attention has been paid to the unique problems posed by subsection (d)(4).11 First, unlike other enumerated definitions of “sexual assault” in Rule 413(d), the definition in subsection (4) is the only one that doesn’t contain a “non-consent” qualifier,12 meaning that even consensual sexual activities can be “crimes” under the Rule.13 Second, the conduct need not have been charged as a crime; mere allegations of offenses suffice so long as they make out the elements of a crime.14 However, one of the strangest parts of Rule 413 is that, as applied, the trial judge’s discretion to preclude evidence of prior sexual assaults is much more constrained than the judge’s discretion to admit other non-sexual past crimes, which furthers a presumption in favor of admissibility in such cases.15

Here, I propose a simple amendment to Rule 413, which makes clear that a “sexual assault” is only an act performed without consent. First, I outline the contentious and unique history of the enactment of this series of rules. Second, I conduct a brief survey of American jurisdictions that either criminalize BDSM conduct or decline to recognize consent as a defense to assault or battery, and I identify the jurisdictions in which these provisions overlap with unexpected and unfortunate effect. Third, I critique the underlying proposition that prior BDSM acts are relevant or probative of propensity to commit sexual assault, which undercuts any rational justification for the rule. Finally, I demonstrate how simple and common-sense amendments to Rule 413 can alleviate some of these concerns.

II. The Enactment and Development of Rule 413

Rule 413 didn’t result from any groundswell of opposition to the normal operation of the character evidence rules. Rather, Rule 413 was rolled up into the hotly-contested Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act signed into law by President Clinton in 1994.16 Rule 413 was developed by Department of Justice Senior Counsel David Karp and introduced in the House by Representative Susan Molinari.17 The rule was intended to “authorize admission and consideration of evidence of an uncharged offense for its bearing ‘on any matter to which it is relevant’ . . . includ[ing] the defendant’s propensity to commit sexual assault.”18 While Representative Molinari did briefly address Rule 413 during the floor debate, she focused her remarks on Rule 414 (the provisions relating to sexual offenses against children), and she specifically referred to “an unusual disposition . . . a sexual or sado-sexual interest in children—that simply does not exist in ordinary people.”19 The same provisions at issue during the floor debate were inserted into Rule 413 without explanation.20

The proposal certainly had its detractors, and the rule’s procedural history was particularly controversial. Ordinarily, changes to procedural and evidentiary rules are recommended by the Advisory Committee as per the Rules Enabling Act21 due to the “exacting and meticulous care” required in drafting amendments.22 Rule 413 was an anomaly; the rule changes were “based on a Senate amendment that . . . had maybe 20 minutes of debate.”23 The substance of the rule also drew ire. One vocal critic on the floor, a former prosecutor, noted in a rare moment of Congressional self-awareness: “I know . . . we all . . . try to be ‘tough on crime,’ but this is ridiculous.”24

But Representative Molinari had unique leverage—she was a “no” vote on the first version of the bill, which had not incorporated her proposal, and which had failed by a margin of only several votes.25 In the second draft, Representative Molinari’s proposal was included as a way to court her vote, but with a caveat: Rules 413–415 would be submitted to the Judicial Conference of the United States for recommendations. If the Judicial Conference objected, Congress represented that it would take 150 days to reconsider before the laws become effective.26

The Judicial Conference’s response was unambiguous. In its report, the Conference criticized the “underlying policy,” “drafting ambiguities,” and “possible constitutional infirmities” of the new rules and urged their rejection.27 Members and commentators were almost unanimous in their opposition—which the Judicial Conference itself noted as “highly unusual.”28 As an alternative, the Judicial Conference suggested incorporating simplified versions of the rules into Rule 404(a).29 But neither scholars nor practitioners have a vote in Congress. After 150 days of Congressional inaction, the rules took effect as enacted.30

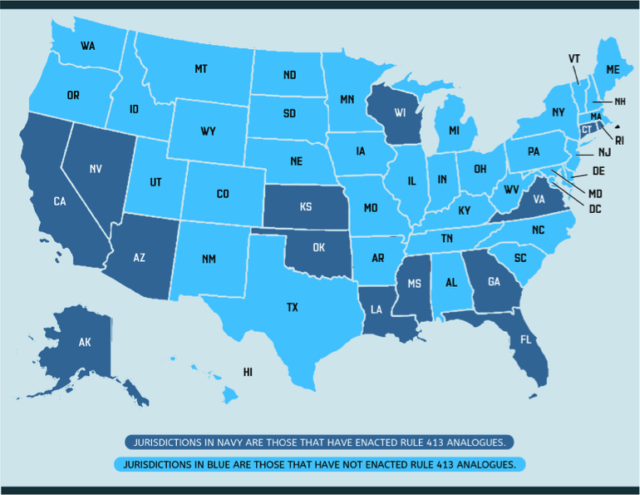

Thus far, only a small minority of states have adopted an analogue to Rule 413 (“413 jurisdictions”).31 In non-413 jurisdictions, broader rules on the admissibility of character evidence govern instead. In some of those jurisdictions, either statute or judicial precedent provides that evidence of prior sexual acts on the part of the defendant is inadmissible to prove the defendant’s propensity to commit similar acts,32 while in other jurisdictions, at least in some circumstances, admission of prior sexual acts is permitted to prove propensity.33

Figure 1. Rule 413 analogues

This survey34 comes with several caveats. First, even in jurisdictions that prohibit admission of prior sexual acts to prove propensity, such evidence may be introduced for any number of other purposes, including to prove identity;35 motive;36 intent;37 plan, preparation, or modus operandi;38 opportunity;39 or lack of consent, use of force, or absence of mistake,40 among others. In short, prior sexual acts frequently find themselves in evidence despite the many safeguards designed to limit their evidentiary uses.41

Second, some jurisdictions’ evidence codes permit even non-criminal sexual acts to be admitted to prove propensity.42 For example, a Connecticut court ruled that the introduction of the defendant’s possession of a pornographic magazine depicting “young-looking women”—adult women—was admissible in a child sexual assault trial.43 In Louisiana, the legislature amended its evidence code to permit the introduction of “acts involving sexually assaultive behavior” and legislators expressly acknowledged that this amendment was written to encompass even legal sexual activity.44 During consideration, scholarly testimony squarely expressed concern “over the admissibility of hypothetical evidence [that] the accused has a preference for ‘rough sex.’”45 And in a recent Georgia rape case, the court permitted the prosecution to play a part of a pornographic DVD depicting bondage owned by the defendant. The video was admitted because the rape victim’s hands had been bound during the assault, and the defendant’s ownership of commercial bondage porn evinced a “lustful disposition” toward bondage.46

Thirdly, Rule 413 and its state counterparts regulate the admission of evidence in “sexual assault” cases only. Courts may admit evidence of a defendant’s engagement in BDSM-related activities in other cases according to general principles of character evidence.47 As for other non-BDSM prior sexual act evidence, courts are generally permissive but more reluctant.48

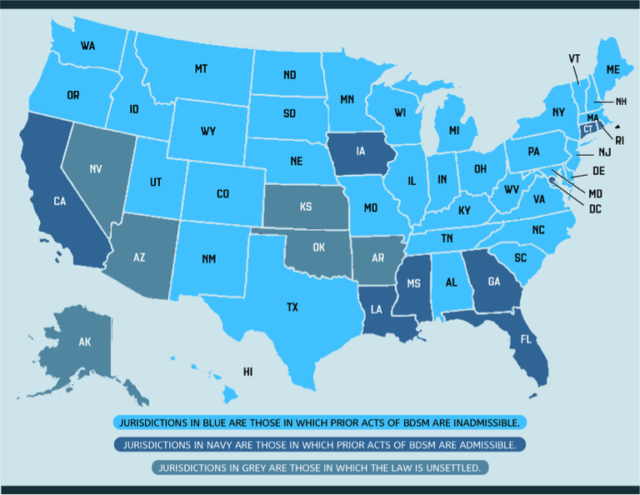

Figure 2. State court admissibility of prior acts of BDSM to prove propensity

Federal courts have uniformly held Rule 413 constitutional, so long as Rule 40349 safeguards, including the trial court’s ability to exclude based on a disproportionate possibility of undue prejudice, remain in place to ensure due process.50 But often, Rule 403 safeguards are either illusory or overstated.51

For example, the Third Circuit has instructed lower courts that “the exclusion of relevant [Rule 413] evidence under Rule 403 should be used infrequently, reflecting Congress’ legislative judgment that the evidence ‘normally’ should be admitted.”52 The 403 balancing is colored from the beginning by this prior legislative judgment, and “Rule 403 must be applied to allow [the] Rule . . . its intended effect”—i.e., admission of the evidence.53 Such understandings don’t write Rule 403 out of the picture entirely, but they can come close.

This does not bode well for defendants. Consider the following facts:54 A defendant is on trial for a rape in which the victim’s hands are bound. The prosecution calls a former sexual partner of the defendant, who intends to testify that the defendant once bound his or her hands during sex, or enjoyed aggressive or rough sex. Since this could constitute a crime under Georgia law,55 there would be little standing in the way of admission—after all, the legislative judgment is that “sexual assaults” lend themselves to propensity, and under the law of the state, he has committed a “sexual assault.”

Once the evidence is admitted, its potential impact is broad. In some circuits, trial judges are expressly advised against giving limiting instructions on evidence admitted through Rule 413,56 since the Rule itself permits consideration on “any matter to which it is relevant.”57 And, even in jurisdictions where limiting instructions are allowed, there is much reason to doubt their effectiveness.58 No less a jurist than Learned Hand considered limiting instructions a mere “placebo,”59 requiring jurors to perform a “mental gymnastic . . . beyond, not only their powers, but anybody’s else.”60 When it comes to sexual taboos, which run particularly deep in the human psyche,61 limiting instructions seem especially superficial.

III. Subsection (d)(4)—The Problem

Rule 413(d)(4) has never been interpreted by the federal courts, so we begin with a blank slate.62 As mentioned above, little relevant guidance appears in any of the legislative history. This can cut both ways, of course. On one hand, one could infer that the omission of the phrase “without consent” was a mere scrivener’s error that does not correctly convey the legislature’s intent, and therefore the reader should simply ignore the omission.63 On the other hand, one could also infer that the drafting legislators implicitly assumed that no person would consent to “bodily injury” or “physical pain,” and this assumption is embodied in the Rule as a substantive policy judgment. As broadly as Rule 413 sweeps, it does not appear to have been Congress’s intent to include consensual sex in the definition of “sexual assault.” However, this is how Rule 413 operates.

The phrase “without consent” appears only in subsections (2) and (3), but not (1), (4), and (5).

(d) Definition of “Sexual Assault.” In this rule and Rule 415, “sexual assault” means a crime under federal law or under state law (as “state” is defined in 18 U.S.C. § 513) involving:

(1) any conduct prohibited by 18 U.S.C. chapter 109A;

(2) contact, without consent, between any part of the defendant’s body—or an object—and another person’s genitals or anus;

(3) contact, without consent, between the defendant’s genitals or anus and any part of another person’s body;

(4) deriving sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting death, bodily injury, or physical pain on another person; or

(5) an attempt or conspiracy to engage in conduct described in subparagraphs (1)–(4).64

The governing principles of statutory interpretation in such situations are clear:

When the legislature uses a term or phrase in one statute or provision but excludes it from another, courts do not imply an intent to include the missing term in that statute or provision where the term or phrase is excluded. Instead, omission of the same provision from a similar section is significant to show different legislative intent for the two sections.65

Therefore, without meaningful extrinsic guidance, the most appropriate inference is that the omission in subsection (4) is intentional.

Another key term is the verb “inflict,” by which the statute refers to inflicting “death, bodily injury, or physical pain.”66 As defined by Oxford Dictionary, to “inflict” is to “[c]ause (something unpleasant or painful) to be suffered by someone or something” or to “[i]mpose something unwelcome on.”67 It could be the case that by using the term “inflict,” by definition the rule does not reach consensual acts, since it is impossible to “[i]mpose something unwelcome on” someone who consents to the imposition.68 On this interpretation, non-consent is already baked into the concept of “inflict[ion].”

This is plausible, but not natural. On this interpretation, whether or not something is an “infliction” is context-dependent—the context, of course, being whether or not the “infliction” is consented to. Or, to use the phraseology of the Oxford Dictionary, the “unwelcome” thing is one to which I do not consent right now. But a more natural interpretation would be that a thing may be “inflict[ed]” upon somebody not if that person does not consent, but rather, if the “inflict[ion]” has generally negative characteristics. It is not possible to “inflict” upon me a slice of pie, even if I am full. However, it is possible to “inflict” pain upon me, even if I consent to and enjoy it. Consider one person (let’s call him Albert) pleading of the other (let’s call him Armand): “Go ahead—hit me. Go on.”69 If Armand then hit Albert, Albert would feel pain, even if he consented to it, and it would still be correct to say that “Armand inflicted pain on Albert.” Therefore, we find no recourse in a creative interpretation of the term “inflict.”

The last hope of avoiding the interpretive problem is the canon of constitutional avoidance, which provides that given two possible interpretations of a statute—one that implicates constitutional concerns and one that does not—the latter interpretation must prevail.70 But this interpretive principle steps in only when a constitutional right is endangered. Litigators have tried to bring BDSM within the principle of Lawrence v. Texas, which enshrined substantive due process protection against prosecution for “sodomy.”71 But Lawrence itself contains a limiting principle: in an especially opaque passage, Justice Kennedy writes that the government generally may not “define the meaning of the [sexual] relationship or to set its boundaries absent injury to a person or abuse of an institution the law protects.”72 Thus far, every court to confront the issue has agreed, holding that there is no due process right to engage in BDSM conduct.73 Since no constitutional rights are implicated,74 no constitutional problems are posed.75

The text of Rule 413 is clear: a “sexual assault” under the Rule can be consensual. On this understanding, there is no need to debate whether the omission of the phrase “without consent” was or was not intended to effect this result; Congressional intent is essentially irrelevant. The Supreme Court has repeatedly (albeit inconsistently) noted that there is no interpretive paradigm which empowers the reader to “attempt to create ambiguity where the statute’s text and structure suggest none.”76 To interpret Rule 413 otherwise would be to do just that.

IV. The Criminalization of BDSM in the United States

One of the few restrictions on the admission of prior acts under Rule 413 is that the prior act must be a “crime” under federal or state law.77 Therefore, a brief survey of BDSM criminalization is necessary.78

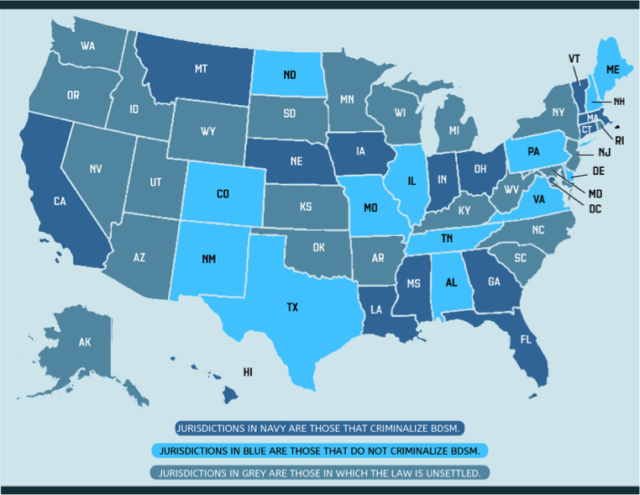

The problematic status of BDSM in American law originates from two contradictory principles inherited from Anglo-American jurisprudence.79 Originally, the governing principle permitted a person to consent “practically to anything.”80 But as a result of the growing penal power of the state, the victim became increasingly excluded from the penological process, and “an individual lost the power to consent to what the state regarded as harm to itself.”81 More recently, issues of consent to battery and assault have arisen with respect to sports82 and body modification,83 and even some statutes governing conduct in a duel remain on the books.84

Following the principle from the seminal British case Regina v. Brown,85 many jurisdictions hold, either by statute86 or precedent,87 that consent is no defense to an assault and battery charge (collectively, “anti-BDSM jurisdictions”). But the Model Penal Code expressly recognizes consent as a defense to criminal assault or battery if “the bodily injury consented to or threatened by the conduct consented to is not serious.”88 In the spirit of the MPC, several jurisdictions provide—either by statute89 or precedent90—that consent is a permissible defense. Other jurisdictions hold that consent may be a defense, but place limits upon that principle that range from practical to arbitrary.91 In a significant number of jurisdictions, neither statute nor precedent address the issue with any clarity.92

Figure 3. BDSM laws by jurisdiction

BDSM is rarely, if ever, criminalized by way of a targeted penal law. Rather, the prohibition’s origin lies in a statute of general applicability, prohibiting assault, battery, or strangulation, to which courts refuse to recognize a defense of consent, which achieves substantially the same result: criminalization. Because of this framework, the fact that the defendant did or did not “deriv[e] sexual pleasure” from the encounter is wholly irrelevant to the mens rea inquiry with respect to the crime or act at issue.

Rule 413(d) requires the crime to “involv[e] . . . deriving sexual pleasure or gratification . . . .”93 At first glance, one plausible interpretation could be that, for the proponent to admit evidence of prior charges, the Rule requires the original criminal act to be defined as one in which the defendant derived sexual pleasure. This interpretation would be a favorable one for BDSM practitioners, since the crimes of assault or battery do not contain as an element any requirement that the defendant derive sexual pleasure. But this interpretation seems unlikely. In United States v. Foley,94 the defendant made a similar claim, and argued that in applying Rule 413 to prior conduct, courts must take a “categorical approach” inquiry: all prior crimes must definitionally correspond to the text of Rule 413 (i.e., as outlined in the relevant penal law, not as committed in fact).95 However, the Seventh Circuit rejected this argument, holding instead that courts must analyze the underlying facts of the prior act to determine whether it falls within the ambit of the Rule.96 The Seventh Circuit’s conclusion is unfortunate, but there is no reason to believe that it is incorrect, as it seems congruous with Congressional policy of liberal admission.

V. BDSM and Propensity

Why admit evidence of acts of prior sexual assault at all? The justification, broadly speaking, is spelled out in two propositions: (1) a person who commits one sexual assault is more likely to commit another than someone who has never before committed a sexual assault; and (2) that likelihood is stronger than in other propensity connections, in a way that justifies a special rule recognizing the connection.97 For purposes of this article, I reserve decision on whether this justification is a sound one. But even if we assume as much, the logic of Rule 413 remains internally incoherent. Since Rule 413(d)(4) includes BDSM in the definition of “sexual assault,” to survive scrutiny, it must follow that a person who engages in BDSM activity is more likely to commit a sexual assault than someone who does not (hereinafter “the BDSM propensity proposition”). Otherwise, evidence of prior BDSM acts would be irrelevant,98 and certainly more prejudicial than probative.99

But the BDSM propensity proposition is theoretically and empirically flawed. Social theory, almost universally, has long resisted the impulse to draw a straight line from a person’s non-traditional sexual desires to the content of their character. Following Freud’s assertion that “sadism and masochism cannot be attributed merely to the element of aggressiveness,”100 Jacques Lacan flatly refused to consider sadism “a register of a kind of immanent aggression.”101 Michel Foucault considered sadomasochism a “massive cultural fact”—less violence, more theatre—constituting “one of the great conversions in the Western imagination—unreason transformed into the delirium of the heart, the madness of desire, and an insane dialogue between love and death in the limitless presumption of appetite.”102

Empirically, no evidence exists that BDSM practice or interest predicts future violence.103 At the very least, no supporting evidence exists in the Congressional Record. Further, there appears to be no evidence to suggest that dominant partners are more likely than submissive partners to commit a sexual assault—i.e., a nonconsensual sexual act.104 But Rule 413 makes such an assumption—and that assumption only makes sense if we understand dominant partners as aggressive people at the core of their psyche.105 After all, subsection (d)(4) only reaches the “deriving [of] sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting . . . death, bodily injury, or physical pain . . .”106 Since Rule 413 places the defendant in the active subject role in the sentence, the Rule would only apply if the defendant is doing both the “deriving” of pleasure and the “inflicting” of pain. In theory, the Rule would not apply to a submissive or masochistic defendant, who derives pleasure from receiving pain.

Over the last decade, there has been a steady movement toward de-pathologizing BDSM conduct.107 While the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders identifies both “sexual sadism disorder” and “sexual masochism disorder” as paraphilic disorders,108 the new diagnostic preferences—in response to medical and psychological scholarship on the issue109—recommend diagnosis only if “the behaviors cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” or “if the person has acted on these sexual urges with a nonconsenting person.”110 Implicit in these changes is a rejection of the BDSM propensity proposition—by de-pathologizing consensual sexual acts and inclinations, the American Psychiatric Association affirms that sadomasochism in itself poses no risk to health or safety.

This is not to say there is complete consensus. Judges and scholars in numerous disciplines cite hesitations as to both the normative permissibility of BDSM and the appropriateness of decriminalization.111 Concerns range widely,112 but they can be placed into one of several categories. First, critics raising normative objections disagree that no harm is done: some argue that BDSM is a “breach of the peace” and inflicts harm on the public as a whole,113 while others argue that BDSM constitutes a dignitary harm to the submissive partner.114 Second, critics raising social objections worry that BDSM legalization (and the accompanying social acceptance) could lead to the glorification and encouragement of sexual violence or objectification.115 Third, critics raising pragmatic objections argue that BDSM poses risks of non-consent and mistake of fact as to the consent of the submissive partner, which sets it apart from other sexual activities116 and makes domestic violence and sexual assault more difficult to prove.117

The intricacies of such arguments and the responses to them are beyond the scope of this article. Many of these arguments are identified and sufficiently refuted by Margo Kaplan, who notes in her article that many, if not all, of these arguments rest on a normative devaluation of the importance of sexual pleasure and autonomy in the overall well-being and security of personhood.118

The gist is this: Popular culture has seen a general liberalization of sexual attitudes toward BDSM and kink over the last couple decades,119 and there has been a parallel process of BDSM de-pathologization by the medical community. It is time the law followed suit.

VI. Subsection (d)(4)—The Solution

Rule 413 should be repealed in full. However, the problems identified in this article can be solved in a less radical way. Rule 413 should define sexual assault as “non-consensual,” a qualifier already present in subsections (d)(2) and (d)(3). The effect of such a change would distribute the qualifier to all subsections. As amended, the rule would read:

(d) Definition of “Sexual Assault.” In this rule and Rule 415, “sexual assault” means a crime under federal law or under state law (as “state” is defined in 18 U.S.C. § 513), committed without consent, involving:

(1) any conduct prohibited by 18 U.S.C. chapter 109A;

(2) contact, without consent, between any part of the defendant’s body—or an object—and another person’s genitals or anus;

(3) contact, without consent, between the defendant’s genitals or anus and any part of another person’s body;

(4) deriving sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting death, bodily injury, or physical pain on another person; or

(5) an attempt or conspiracy to engage in conduct described in subparagraphs (1)–(4).

This revision will make clear to the courts that no sexual act should be considered for propensity purposes unless the act itself was nonconsensual. This rule excludes state crimes that do not definitionally require the act to be “committed without consent”—no matter how the state defines it. The effect is to refocus the evidentiary rule on its appropriate object—nonconsensual sexual acts—which more closely aligns with the Rule’s original legislative intent.

This change poses an interpretive problem of its own: in anti-BDSM jurisdictions, courts hold (or statutes provide) that a person cannot consent to an assaultive act. Since the Rule permits the state law to define the underlying crime, one plausible interpretation could be that this amendment intends, in much the same way, to defer to state law on the issue of what constitutes legally valid consent. This would, of course, defeat the point. An independent definition of consent would eliminate this possibility. I therefore propose the following:

(e) Definition of “Consent.” In this rule, “consent” means a voluntary and revocable agreement to participate in a sexual act with the defendant.

Lastly, I address one additional, albeit strange, interpretive problem.120 As worded, these amendments provide that a prior sexual act is inadmissible if it results in a person’s death, just because the other person may “consent” to death. This seems an undesirable conclusion.121 Therefore, a proviso is necessary:

(e) Definition of “Consent.” In this rule, “consent” means a voluntary and revocable agreement (except an agreement concerning death) to participate in a sexual act with the defendant.

No rule can be drafted so perfectly as to eliminate the ever-present specter of ambiguity.122 But hopefully, these amendments will leave the rest of Rule 413 intact, and effect only the desired change: removing BDSM from the definition of “sexual assault.”

VII. Conclusion

In the words of Foucault, “the idea that S&M is related to a deep violence—that S&M practice is a way of liberating this violence, this aggression—is stupid.”123 But the rules of evidence incorporate such a notion, presupposing not only that BDSM is “relevant” to the inherent violence of sexual assault, but that BDSM and sexual assault are close enough in fact to be the same at law. Once this proposition is captured and properly rejected, Rule 413(d)(4) loses all pretense to rationality.

Based on the text, context, and legislative history of Rule 413, my interpretation of Rule 413 is the only permissible one. That is a problem—the statutes and decisions criminalizing consensual BDSM are an immoral intrusion into the intimate lives of people and are arguably unconstitutional, and the Federal Rules of Evidence should mitigate the impact of those laws, rather than expand it. Further, an amendment will serve other purposes. Since their promulgation, the Federal Rules have served as a model for state evidence codes, in substance and in form.124 This amendment will also serve as such a model, and though its effect is narrow—mitigation of the collateral consequences of BDSM criminalization—hopefully it will be the start of legislative movement toward wholesale decriminalization of consensual sexual conduct.

Appendix 1: Proposed Revision to Rule 413

Rule 413. Similar crimes in sexual assault cases

(a) Permitted Uses. In a criminal case in which a defendant is accused of a sexual assault, the court may admit evidence that the defendant committed any other sexual assault. The evidence may be considered on any matter to which it is relevant.

(b) Disclosure to the Defendant. If the prosecutor intends to offer this evidence, the prosecutor must disclose it to the defendant, including witnesses’ statements or a summary of the expected testimony. The prosecutor must do so at least 15 days before trial or at a later time that the court allows for good cause.

(c) Effect on Other Rules. This rule does not limit the admission or consideration of evidence under any other rule.

(d) Definition of “Sexual Assault.” In this rule and Rule 415, “sexual assault” means a crime under federal law or under state law (as “state” is defined in 18 U.S.C. § 513), committed without consent, involving:

(1) any conduct prohibited by 18 U.S.C. chapter 109A;

(2) contact, without consent, between any part of the defendant’s body—or an object—and another person’s genitals or anus;

(3) contact, without consent, between the defendant’s genitals or anus and any part of another person’s body;

(4) deriving sexual pleasure or gratification from inflicting death, bodily injury, or physical pain on another person; or

(5) an attempt or conspiracy to engage in conduct described in subparagraphs (1)–(4).

(e) Definition of “Consent.” In this rule, “consent” means a voluntary and revocable agreement (except an agreement concerning death) to participate in a sexual act with the defendant.

Appendix 2: Comparison of BDSM Laws and Rule 413 Analogues

| Jurisdiction | BDSM laws | 413 analogue | State court admissibility | Federal court admissibility |

| Alabama | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Alaska | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| Arizona | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| Arkansas | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| California | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Colorado | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Connecticut | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Delaware | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| District

of Columbia |

Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Florida | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Georgia | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Hawai’i | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Idaho | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Illinois | Legal | Admissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Indiana | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Iowa | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity125 | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Kansas | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| Kentucky | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Louisiana | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Maine | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Maryland | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Massachusetts | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Michigan | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Minnesota | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Mississippi | Illegal | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Missouri126 | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Montana | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Nebraska | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Nevada | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| New Hampshire | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| New Jersey | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| New Mexico | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| New York | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| North Carolina | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| North Dakota | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Ohio | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Oklahoma | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| Oregon | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Pennsylvania | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Rhode Island | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| South Carolina | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| South Dakota | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Tennessee | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Texas | Legal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Utah | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Vermont | Illegal | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Admissible for propensity |

| Virginia | Legal | Admissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity |

| Washington | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity127 | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| West Virginia | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

| Wisconsin | Unsettled | Admissible for propensity | Unsettled | Unsettled |

| Wyoming | Unsettled | Inadmissible for propensity | Inadmissible for propensity | Unsettled |

Suggested Reading

Revenge Porn Legislation Activists and the Lessons from Sexual Harassment Jurisprudence: Gender Neutrality, Public Perceptions, and Implications

Amy Lai ∞ I. Revenge Porn Gender‑Neutral Legislation and Gender‑Focused Advocacies II. What Anti‑Revenge Porn Activists Can Learn from Gender Neutrality and Sexual Harassment Jurisprudence III. Gender‑Neutral Advocacies and Their Potentials IV. Conclusion To date, twenty‑six states have laws that expressly

Sex Abuse Validation Testimony: Ripe for a Frye Challenge

Max R. Selver∞ I. Introduction New York Family Courts routinely admit “validation testimony” in cases involving allegations of child sexual abuse. Validation testimony consists of a mental health professional’s opinion that a child’s behavior is consistent with the occurrence of