Caged Creativity

Introduction

John Hovey ∞

Hovey reflects on our shared humanity, the dehumanizing experience of incarceration, and how society’s problems, like a pandemic, are prison problems. He explores his journey as an author and an artist and the “undesirable necessity” of “prison writing.”

Why cartoons and comics? Why commentary? Why anything?

In discussions of Social Justice, or the Criminal Justice System, or the Prison Industrial Complex, a prisoner can be a convenient witness, a genuine literal insider as it were. Sometimes prison problems become society’s problems, but more often, the issues that affect free society impact prisons as well…disease and epidemics for instance.

From the moment COVID-19 infected the American penal system, individuals and organizations were asking me to write about the pandemic experience within the prisons. I was hesitant, but I consented, since it was such an important subject that affected so many.

Like many people, I’ve been writing since I was a child. And I’ve been writing about injustice and incarceration ever since I myself was wrongfully convicted and imprisoned as a teenager, so very long ago, in the Orwellian year 1984. And yet, to me, “prison writing” has always been an undesirable necessity, a duty, whereas creative expression, fiction and art and cartooning for example, is a passion more closely aligned to my interests.

I often write that criminals are much more than just the worst five minutes of their lives, that no matter how heinous their behavior – or even a single anomalous action – has been, it is still only one facet of a complex human being with a lifetime of experiences good and bad…

Similarly, prisoners are more than just criminalized commodities in cages; they aren’t an aberrant separate species or race, or abhorrent freak of nature, they are citizens who were incarcerated because of an action or accusation, something that can happen to anyone anywhere, whether guilty or innocent. Sometimes prisoners are well-rounded individuals, some even possess a wide range of skills and talents and interests beyond the criminal.

A few prisoners are writers who became incarcerated, but there are many more prisoners who began to write once incarcerated, and often because of it. Until recent years, there weren’t many forums inviting the prisoner perspective. Giving voice to prisoners (and to all marginalized disenfranchised communities) is both a noble goal and an absolute necessity, and yet…to believe prisoners can ONLY write about prison, or worse, to only allow prisoners to write about prison, is a different kind of oppression; it reduces them to mere stereotypes and declares their existence should be solely defined by incarceration. It ignores any uniqueness and memories and imagination they may possess, and helps assure they remain two-dimensional subhuman vilified victims, marginalization sometimes made more insidious by specious good intentions.

Personally, I’ve always preferred to express my thoughts and imagination in myriad ways, through articles or speeches, artwork or stories, novels or cartoons, sculpture or scripts – whatever I feel is the best project to convey a particular idea. But because I’m a prisoner – a status that renders me oppressed and ostracized – producing and sharing anything with the world has always been extremely difficult, and the majority of my creation over the decades has been disseminated under pseudonyms. I’ve never even seen the Internet. (I can almost hear the collective gasps of a billion Millennials.)

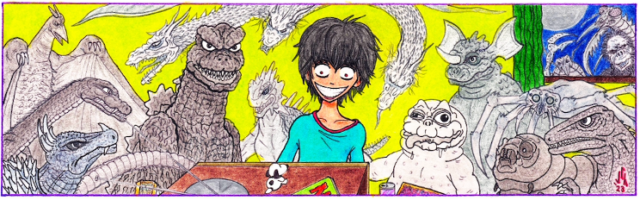

The accompanying corona-cartoons (drawn during the pandemic) can be viewed and interpreted as a quick throwaway laugh, or as social commentary about alienation and oppression (respectively), or both, or anything. Similarly, even the recent accompanying Godzilla cartoon was interpretive—is it simply representational of one imaginative child’s enthusiasm watching monster movies on TV in the Seventies, or is it darkly allegorical, suggesting childhood innocence constantly threatened by the inexplicable monstrousness of modern life? One should never underestimate the importance of art; it can portray complicated truths in a universally understood manner, sometimes in an accessibly fun or silly way.

When discussing social issues (including the coronavirus pandemic), I’ve written countless articles and essays and stories and more, and yes, sometimes created artwork and cartoons. As they say, a picture can be worth a thousand words…and a cartoon panel can express multifaceted issues both subtle and overt at a glance, as well as add a layer of emotion or artistry or entertainment to subjects that may otherwise be dry or grim.

An intellectual or creative person shouldn’t be limited or lobotomized simply for being incarcerated, although this is precisely what happens. Penal systems are designed for regimented conformity – they destroy any hint of individuality, including intellectual/creative/artistic expression, they loathe talent and imagination, they fear empowerment and intelligence, they want prisoners to know their place, they hate when prisoners dare to hope and dream rather than remain despised, exploited, abandoned, and forgotten. Meaningful Freedom of Expression (as well as most other basic rights) is often denied to prisoners. Unfortunately, these attitudes are not limited to penal employees; prisoners encounter prejudice and demonization from society all the time (even from the publishing and entertainment industries), after all, prisoners are the only minority everyone is allowed and encouraged to openly hate.

We must never forget, anyone on earth can become a prisoner, and many will, especially when uneducated and impoverished, but every prisoner is also still a real living complex human being and can be more than just the monster in the cage if only given the opportunity.

1

2

—“Godzilla illustration (self-portrait of author at age six) reprinted with permission, courtesy of G-FAN Magazine #141 (2023).”

Suggested Reading

Corona Drive-Through

A Washington prisoner gets a glimpse of small-town holiday Americana during the pandemic...

Isolation While at Fishkill

"The lack of cleaning supplies and access to cold water (the water was somehow swtiched to hot only) further complicated my experience in isolation."