Consumer Protection and Tax Law: How the Tax Treatment of Attorney’s Fees Undermines the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act

Introduction

Joanna Laine∞

Abstract

Almost forty years after the passage of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), abusive debt collection practices continue to wreak havoc on the lives of low- and moderate-income Americans. The FDCPA aims to prevent these abuses by relying in part on individual consumers to enforce the FDCPA’s fair debt collection rules. Consumer plaintiffs serve as “private attorneys general” by bringing lawsuits against abusive debt collectors, thereby deterring abusive debt collection activity. In order to encourage FDCPA actions in furtherance of the public interest, the FDCPA contains a statutory “fee-shifting” provision whereby a prevailing plaintiff can win attorney’s fees and costs paid by the defendant.

Unfortunately, current tax law creates an obstacle to the enforcement of the FDCPA by individual plaintiffs: attorney’s fee awards are considered part of the plaintiff’s “gross income” for federal income tax purposes. Attorney’s fees may be deducted from income “below-the-line,” but such deductions are subject to significant limitations. Therefore, prevailing FDCPA plaintiffs may end up paying substantial additional taxes as a result of the attorney’s fees included in their FDCPA awards. As illustrated in this article, it is possible for a plaintiff to even lose money by bringing an FDCPA action and subsequently being taxed on the award. Because the potential tax burden may deter consumers from bringing FDCPA actions, the taxation of FDCPA attorney’s fee awards undermines the FDCPA’s goal of using “private attorneys general” to hold debt collectors accountable for their illegal conduct.

This article argues that attorney’s fees awarded under the FDCPA—and under all other fee-shifting statutes—should not be included in the plaintiff’s income. This article first discusses the standard justifications for including attorney’s fees awards in the plaintiff’s income, and explains why these justifications have no merit in the FDCPA context. This article then outlines various strategies for changing the law, including litigation, Congressional action, and regulatory clarification of the Tax Code. Finally, this article discusses strategies that consumer lawyers can use to minimize or eliminate the tax burden that their clients suffer as a result of the inclusion of FDCPA attorney’s fee awards in their clients’ income.

I. Introduction

Almost forty years after the passage of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act (FDCPA), which aimed to “eliminate abusive debt collection practices by debt collectors,”[1] abusive debt collection practices continue to wreak havoc on consumers’ lives.[2] Debt collection has become a multi-billion dollar industry[3] that targets 14% of American adults each year.[4] Each year, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) receives more consumer complaints about debt collectors than about any other industry.[5] Although not all complaints about debt collectors arise out of illegal activity, and not all debt collectors engage in abusive behavior, the debt collection industry as a whole is fraught with abusive practices.[6] For example, debt collectors sue consumers without verifying that the alleged debts are owed, harass consumers over the phone, and make fraudulent representations in order to induce consumers to pay alleged debts.[7]

The FDCPA aims to prevent debt collection abuses by relying on both government agencies and individuals to enforce the Act. The FTC and the newly-formed Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) have joint enforcement authority over the debt collection industry, and they can issue fines and bring lawsuits against debt collectors that violate the law.[8] However, the FTC and CFPB have limited capacity to regulate the debt collection industry along with all of the other industries under their watch.[9] Therefore, government oversight is critically supplemented by private lawsuits brought by individual consumers.[10]

Under section 1692k of the FDCPA, individual consumers (and classes of consumers) may bring lawsuits against debt collection companies that have engaged in abusive practices.[11] This provision has a dual purpose: it allows consumers to obtain recovery for injuries they suffered at the hands of abusive debt collectors and it promotes the public interest goal of deterring abusive debt collection practices. For this reason, section 1692k of the FDCPA may be referred to as a “private attorney general” provision,[12] since “private” individual litigants supplement public enforcement agencies to punish abusive debt collectors and deter future debt collection abuses. To encourage these so-called “private attorneys general” to bring lawsuits, the FDCPA contains a fee-shifting provision whereby winning plaintiffs are entitled to attorney’s fees and costs paid by the defendant, in addition to whatever damages the plaintiffs receive.[13] Thus, low-income consumers with potentially-victorious FDCPA claims can bring lawsuits against debt collectors even if they lack the funds to hire an attorney. Further, all consumers with FDCPA claims may bring lawsuits even if the value of their damages award is likely to be less than the attorney’s fees and costs associated with bringing the case.[14]

Unfortunately, current tax law creates a major obstacle to individual litigants’ ability to enforce the FDCPA. Under the tax code, damages awarded in FDCPA actions, including attorney’s fees, are considered part of the plaintiff’s “gross income.”[15] Even though attorney’s fees in FDCPA cases are collected by the attorney, they are deemed to be income to the plaintiff. This is part of a general rule delineated by the Supreme Court in the 2005 case Commissioner v. Banks: when a litigant’s recovery constitutes taxable income, such income includes the portion of recovery paid to the litigant’s attorney as a contingent fee.[16] The same attorney’s fees can be deducted from the taxpayer’s income as an expense incurred “for the production or collection of income,”[17] but because this is a “below-the-line” deduction (as opposed to an “above-the-line” deduction),[18] the deduction does not fully eliminate the tax burden that may arise from the initial inclusion of the attorney’s fees as income.[19] As a result, winning plaintiffs may end up paying substantial additional taxes as a result of the attorney’s fees awarded to them in FDCPA actions. Further, low-income consumers may lose valuable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC), which are important resources for working-poor individuals and families and are widely heralded as mechanisms for reducing poverty, promoting work, and increasing the well-being of low-income families.[20] The taxation of FDCPA attorney’s fees disincentives consumers from bringing FDCPA actions and prevents plaintiffs from being made fully whole after being injured by a debt collector. In some cases, the plaintiff could even lose money by bringing an FDCPA action and subsequently being taxed on the award.[21]

The inclusion of attorney’s fees in FDCPA plaintiffs’ income undermines the policy goals of the FDCPA. Due to the inclusion of attorney’s fees as part of their income, plaintiffs who were injured by debt collectors are taxed disproportionately high amounts relative to the amount of recovery they truly receive from their lawsuits.[22] Moreover, the taxation of FDCPA attorney’s fee awards is inconsistent with the notion that FDCPA plaintiffs serve as “private attorneys general” who are performing a public service in addition to seeking personal recovery. “The FDCPA enlists the efforts of sophisticated consumers . . . as ‘private attorneys general’ to aid their less sophisticated counterparts, who are unlikely themselves to bring suit under the Act, but who are assumed by the Act to benefit from the deterrent effect of civil actions brought by others.”[23] The very purpose of the attorney’s fee provision is to encourage plaintiffs to bring FDCPA actions, because the rest of society stands to benefit substantially from individual FDCPA actions. Because the attorney’s fees provided in service of an FDCPA action are fees that benefit all of society, not just an individual plaintiff, it is misguided to hold individual plaintiffs liable for income taxes on attorney’s fee awards.

This article argues that attorney’s fees awarded in FDCPA actions—and in all other fee-shifting cases[24]—should not be included in the plaintiff’s income.[25] In recommending this change, this article discusses the standard justifications for including attorney’s fee awards as part of the plaintiffs’ income and argues that these justifications have no merit in the FDCPA context (Part III), and that the taxation of FDCPA attorney’s fees undermines the goals of the FDCPA (Part IV). This article then outlines various routes for reform that advocates can pursue, either through litigation (Part V(A)) or through Congressional or regulatory clarification of the Tax Code (Part V(B)). Finally, this article will discuss strategies that consumer lawyers can use on behalf of individual clients to minimize or eliminate the additional tax burden that their clients suffer due to the inclusion of FDCPA attorney’s fee awards in their clients’ income (Part V(C)).

∞ Poverty Justice Solutions Fellow, Brooklyn Legal Services Corporation A. J.D. 2015, New York University School of Law. I am extremely grateful to Matthew Schedler for inspiring this article and encouraging me to undertake it, to Professor David Kamin for supervising my research and writing, and to Ayalon Eliach for providing invaluable guidance and research recommendations. I would also like to thank Professor Laura Sager and Professor Stephen B. Cohen for their advice. Many thanks to the editors of the N.Y.U. Review of Law & Social Change, particularly Hugh Baran, Claire Glenn, Michael Gsovski, Jacqueline Horani, Bing Le, and Hilary Nakasone for their thorough editing and Alexandra Dougherty, Ryan M. Schachne, and Hillela Simpson for their helpful feedback. The views expressed in this article are my own and do not reflect those of my employer or any of the individuals named herein.

1. Fair Debt Collection Practices Act § 802(e), 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e) (2012).

2. See generally Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Fair Debt Collection Practices Act: CFPB Annual Report 2014 7 (2014), http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/201403_cfpb_fair-debt-collection-practices-act.pdf [hereinafter CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report] (“In 2013, approximately 30 million individuals, or 14% of American adults, had debt in or subject to the collections process averaging approximately $1,400.”); Rick Jurgens & Robert J. Hobbs, National Consumer Law Center, The Debt Machine: How the Collection Industry Hounds Consumers and Overwhelms the Courts 5 (July 2010), http://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/debt-machine.pdf (elaborates in detail the extent to which debt collectors harass consumers to the point where the victim’s bank accounts are drained simply to fight the charges).

3. CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2, at 7.

4. Id. (citing Fed. Reserve Bank of N.Y., Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (Nov. 2013), https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2013Q3.pdf) (stating that, in 2013, approximately 14% of American adults had debt in or subject to the collections process, with alleged debts averaging approximately $1,400).

5. CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2, at 7.

6. Id. at 10.

7. Id. at 11–14, 16–23.

8. 15 U.S.C. § 1692l.

9. See Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Strategic Plan, Budget, and Performance Plan and Report 4–5, 11 (2014), http://files.consumerfinance.gov/f/strategic-plan-budget-and-performance-plan-and-report-FY2013-15.pdf (noting that the CFPB has a very specific budget that cannot be exceeded pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act and engages in numerous efforts including supervision activities at various financial institutions; handling consumer complaints about mortgages, credit cards, and other financial products; and providing digital content and materials to consumers.); Federal Trade Commission, Fiscal Year 2014 Summary of Performance and Financial Information 3–5, 17–21, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/ftc-fy-2014-summary-performance-financial-information/150218fy14spfi.pdf (last visited Apr. 29, 2015) (noting that the FTC has a capped budget and describing the FTC’s numerous activities in the areas of consumer protection, promoting competition, outreach and partnerships, and financial management).

10. Approximately 10,000 FDCPA lawsuits are brought by consumers each year. See WebRecon, What Goes Up… Debt Collection Litigation & CFPB Complaint Statistics, Nov 2015 (Dec. 16, 2015), http://webrecon.com/what-goes-up-debt-collection-litigation-cfpb-complaint-statistics-nov-2015/ (reporting that 10,468 FDCPA lawsuits were filed between January 1, 2015 and November 30, 2015); see also WebRecon, Debt Collection Litigation & CFPB Complaint Statistics, December 2014 and Year in Review (Jan. 22, 2015), http://webrecon.com/debt-collection-litigation-cfpb-complaint-statistics-december-2014-and-year-in-review/ (reporting that 9720 FDCPA lawsuits were filed in 2014).

11. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k.

12. See Gonzales v. Arrow Fin. Servs., L.L.C., 660 F.3d 1055, 1061 (9th Cir. 2011) (“Though the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) is empowered to enforce the FDCPA, 15 U.S.C. § 1692l, Congress encouraged private enforcement by permitting aggrieved individuals to bring suit as private attorneys general.”); Catherine Palo, Litigating Violations of Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 128 Am. Jur. Trials 243, § 3 (2013).

13. See 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a)(3) (“in the case of any successful action to enforce the foregoing liability, [the plaintiff is awarded] the costs of the action, together with a reasonable attorney’s fee as determined by the court”).

14. See Tolentino v. Friedman, 46 F.3d 645, 651 (7th Cir. 1995), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1160 (1995) (justifying market-rate attorney’s fee awards, even when they are many times as great as the plaintiff’s recovery of a mere $1000 in statutory damages, based on the principle that FDCPA plaintiffs function as private attorneys general).

15. Cf. I.R.C. § 61 (Except as exempted by the Tax Code, “[g]ross income means all income from whatever source derived.”).

16. 543 U.S. 426, 431 (2005).

17. I.R.C. § 212(1).

18. An “above-the-line” deduction is a deduction taken directly from a taxpayer’s gross income to arrive at a new amount called “adjusted gross income.” I.R.C. § 62(a) (“For purposes of this subtitle, the term ‘adjusted gross income’ means, in the case of an individual, gross income minus the following deductions . . . ”); William A. Klein, Joseph Bankman, Daniel N. Shaviro & Kirk J. Stark, Federal Income Taxation 353 (15th ed. 2009). An above-the-line deduction is effectively the same as excluding something from income altogether, because above-the-line deductions are not subject to any limitations; a taxpayer may reduce her adjusted gross income by the full amount of any above-the-line deduction. See id. (“Gross Income (§ 61) minus Above the Line Deductions (§ 62(a)) equals Adjusted Gross Income (§ 62)”). Below-the-line deductions, by contrast, are deducted after adjusted gross income is calculated and are subject to various limitations. See id. Therefore, below-the-line deductions are often less helpful to the individual taxpayer than above-the-line deductions. For a more detailed discussion of the difference between above-the-line and below-the-line deductions, see infra Part III(B)(1).

19. See infra Part III(B) for further discussion of the deductibility of attorney’s fee awards. Other features of the tax code, like the Alternative Minimum Tax, prevent below-the-line deductions from fully mitigating the impact of including attorney’s fees as part of adjusted gross income. Id.

20. See Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman & Brandon Debot, Center for Budget & Policy Priorities, EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds (Apr. 3, 2015), http://www.cbpp.org/research/eitc-and-child-tax-credit-promote-work-reduce-poverty-and-support-childrens-development?fa=view&id=3793 (describing the benefits of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit).

21. See infra Part III(C)(2) (describing a hypothetical plaintiff who suffers a net loss after bringing an FDCPA case, winning only $1000 in statutory damages, and subsequently being taxed on her attorney’s fee award).

22. Although the right to seek attorney’s fee awards belongs solely to the plaintiff, the right to collect attorney’s fees belongs to the attorney. See Pony v. Los Angeles, 433 F.3d 1138, 1142 (9th Cir. 2006) (stating that attorney’s fees are paid directly from the non-prevailing party to the plaintiff’s attorney, and therefore never even pass through the hands of the plaintiff herself.)

23. Jacobson v. Healthcare Fin. Servs., Inc., 516 F.3d 85, 91 (2d Cir. 2008)

24. I will discuss this issue almost exclusively in the context of the FDCPA. However, a variety of other consumer protection statutes—including the federal Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(3), and Electronic Fund Transfer Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1693m(a)(3), and state consumer protection laws—also have fee-shifting provisions akin to that of the FDCPA. The same policy arguments justifying the exclusion of FDCPA attorney’s fees as income also apply to attorney’s fees awarded in other statutes with fee-shifting provisions.

25. Or, in the alternative, they may be included as income but deducted from income above-the-line, such that the plaintiffs’ tax burden would not be affected by the attorney’s fee award. See infra Part III(B)(1) (describing the differing tax consequences of above-the-line and below-the-line deductions). Congress could enact an amendment to the tax code modeled after a provision in the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, which amended § 62 of the tax code to allow attorney’s fees awarded in discrimination lawsuits to be deducted above-the-line from adjusted gross income. American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, Pub. L. No. 108-357, § 703, 118 Stat. 1418, 1548 (2004) (codified as amended at I.R.C. § 62 (West 2005)). See infra Part V(B)(1) (describing this statute in greater detail and proposing similar legislation to change the tax consequences of FDCPA attorney’s fee awards).

26. The FDCPA was supplemented by the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, Pub. L. 111–203, 124 Stat. 1376 (codified as amended in scattered sections of 12 U.S.C. & 15 U.S.C.), which regulated a wide variety of financial institutions and included some provisions affecting creditors and debt collectors.

27. 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e).

28. Id. §§ 1692b–1692j.

29. Id. § 1692e(2)(A).

30. Id. § 1692d.

31. Id. § 1692g(a)(4).

32. Id. § 1692l (conferring enforcement authority on the FTC); 12 U.S.C. § 5514 (providing that the CFPB may have enforcement authority over a “larger participant of a market for other consumer financial products or services,” as the CFPB defines by rule); CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2, at 24 (“The Bureau began a critical new chapter in debt collection supervision on January 2, 2013, when the CFPB’s larger participant rule for debt collection became effective. Under this larger participant rule, the Bureau has supervisory authority over any firm with more than $10 million in annual receipts from consumer debt collection activities. This authority extends to about 175 debt collectors, which accounts for more than 60% of the industry’s annual receipts in the consumer debt collection market. This new Federal authority enables the Bureau both to protect consumers and to promote a level playing field for law abiding debt collectors.”).

33. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k.

34. The attorney’s fees awarded in class action lawsuits are not generally included as income for any of the plaintiff class members (not even the named plaintiffs), so the income taxation of attorney’s fees does not pose a problem for class plaintiffs. See Robert W. Wood, Attorneys Fees in Class Actions, Business Law Today Vol. 18, No. 3 (Jan./Feb. 2009) [hereinafter Wood, Attorneys Fees in Class Actions], http://apps.americanbar.org/buslaw/blt/2009-01-02/wood.shtml (explaining that, in “opt-out” class actions, attorney’s fees are not considered income to the class members). Although they won’t be discussed extensively in this article, class action lawsuits are an important component of the FDCPA’s enforcement structure and there have been a growing number of class actions under the FDCPA. National Consumer Law Center, Fair Debt Collection § 6.2.2.2. (8th ed. 2014) [hereinafter Fair Debt Collection] If individual FDCPA actions are hampered by the tax system, consumer lawyers may find value in bringing more class action FDCPA lawsuits so as to avoid imposing negative tax consequences on their clients. See infra Part V(C)(4) (discussing the potential benefit of bringing class action lawsuits as an alternative to individual FDCPA actions with negative income tax consequences).

35. William B. Rubenstein, On What a “Private Attorney General” Is—and Why It Matters, 57 Vand. L. Rev. 2129, 2150–51 (2004)

36. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a)(3).

37. Jacobson v. Healthcare Fin. Servs., Inc., 516 F.3d 85, 91 (2d Cir. 2008) (“In order to prevail, it is not necessary for a plaintiff to show that she herself was confused by the communication she received; it is sufficient for a plaintiff to demonstrate that the least sophisticated consumer would be confused.”); Rosemary E. Williams, Proof Under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 104 Am. Jur. Proof of Facts 3d 1 § 66 (2008).

38. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a)(2)(A).

39. See Matthew R. Bremner, The Need for Reform in the Age of Financial Chaos, 76 Brook. L. Rev. 1553, 1561–62, 1579–81 (2011) (explaining that many FDCPA actions are brought for technical violations that cause consumers no actual harm); Terry Carter, Payback: Lawyers on Both Sides of Collection are Feeling Debt’s Sting, ABA Journal (Dec. 1, 2010), http://www.abajournal.com/magazine/article/payback_lawyers_on_both_sides_of_collection_are_feeling_debts_sting (describing FDCPA attorney who, instead of pursuing actual damages, induces debt collectors to settle cases for statutory damages plus attorney’s fees). “Statutory damages under the FDCPA are intended to ‘deter violations by imposing a cost on the defendant even if his misconduct imposed no cost on the plaintiff.’” Gonzales v. Arrow Fin. Servs., 660 F.3d 1055, 1067 (9th Cir. 2011) (quoting Crabill v. Trans Union, L.L.C., 259 F.3d 662, 666 (7th Cir. 2001). As a practical matter, many, if not most, FDCPA cases end in settlement. Bremner, supra, at 1580. See generally Victor Abel Pereyra & Benjamin Sunshine, Access-to-Justice v. Efficiency: An Empirical Study of Settlement Rates after Twombly & Iqbal, 2015 U. Ill. L. Rev. 357, 372, 387 (2015) (noting that, among prior empirical studies that discuss rates at which federal civil cases are settling, “it seems that they all agree that the settlement rate of federal civil cases is somewhere between 60% and 70%” and reporting results of new study that found aggregate settlement rate of 46.1%). Debt collectors are especially likely to settle those cases which only seek statutory damages, because the value of the $1000 statutory damages award plus attorney’s fees and costs is often less than the cost to the debt collector of litigating an FDCPA action. Id.

40. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a)(1).

41. Fair Debt Collection, supra note 34, § 2.5.2.1 (describing the array of high-value actual damages, and noting that “a common and most costly mistake made by an attorney in a debt collection abuse case is to pay scant attention to the nature and extent of the client’s actual damages.”).

42. Id. § 2.5.2.2.2 (prior FDCPA cases have included injuries such as heart attack, miscarriage, ulcers, diabetic flare-ups, loss of weight, loss of sleep, crying, becoming bedridden, embarrassment, indignation, and pain and suffering).

43. Id. § 2.5.2.2.3. Other out-of-pocket losses include medical or counseling expenses, telephone charges, attorney’s fees incurred defending a debt collection lawsuit, and transportation expenses. Id.

44. Id. § 2.5.2.2.4. These so called “relational injuries” include injury to reputation, loss of privacy, loss of consortium, strain to marriage, strain with family, and humiliation. Id.

45. Patrick Lunsford, Jury Awards Plaintiff $1.26 million in FDCPA Violation Lawsuit, InsideArm (July 31, 2011), http://www.insidearm.com/opinion/jury-awards-plaintiff-1-26-million-in-fdcpa-violation-lawsuit/.

46. Dan Margolies, Jury Awards KC Woman $83 Million in Debt Collection Case, KCUR 89.3 (May 14, 2015), http://kcur.org/post/jury-awards-kc-woman-83-million-debt-collection-case#stream/0.

47. See Fair Debt Collection, supra note 34, § 2.6.

48. See id.

49. Lunsford, supra note 45.

50. Margolies, supra note 46.

51. See, e.g., Cuevas v. Check Resolution Servs., No. 12-0981, 2013 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 189893, at *4 (E.D. Cal. Aug. 7, 2013) (awarding $3515 in attorney’s fees and $749.70 in costs to plaintiff who won $150 in statutory damages under the FDCPA and $100 in statutory damages under a state statute); McDermott v. Marcus, Errico, Emmer & Brooks, P.C., 53 F. Supp. 312, 325 (D. Mass. 2014) (awarding $39,898.10 in attorney’s fees and $2157.60 in costs to plaintiff who won $800 in statutory damages under the FDCPA); Order re: Judgment at 19, McCollough v. Johnson, Rodenburg & Lauinger, L.L.C., 645 F. Supp. 2d 917 (D. Mont. 2009) (No. 1:07-cv-00166) (awarding $107,770.17 in attorney’s fees and costs to plaintiff who won $301,000.00 in actual and statutory damages under the FDCPA), aff’d, 637 F.3d 939 (9th Cir. 2011); Heritage Pacific Financial, L.L.C. v. Monroy, 215 Cal. App. 4th 972, 980–81 (Cal. Ct. App. 2013) (affirming trial court’s decision granting attorney’s fees and costs of $89,489.60 for plaintiff who won $1 in nominal damages under the FDCPA).

52. Robert F. Koets, Annotation, Award of Attorneys’ Fees under § 813(A)(3) of Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, 132 A.L.R. Fed. 477 (1996).

53. Tolentino v. Friedman, 46 F.3d 645, 652 (7th Cir. 1995), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1160 (1995); Fair Debt Collection, supra note 34, § 6.8.6.3.

54. Tolentino, 46 F.3d at 651–652.

55. Id.

56. For example, the Tolentino plaintiff only won $1000 in statutory damages but may have had to pay taxes not only on his damages but on $16,235 in attorney’s fees. See infra Part III(C)(2), for a discussion of the tax consequences for a hypothetical plaintiff based on the plaintiff in Tolentino. Tolentino’s additional tax burden arising from his attorney’s fees would likely have exceeded the $1000 he received in damages. Id.

57. 121 Cong. Rec. E5404-5405 (daily ed. Oct. 9, 1975) (statement of Rep. Annunzio) (introducing the then-named Debt Collection Practices Act).

58. CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2, at 9.

59. Id. at 11–14. Some complaints reported more than one abusive tactic.

60. Id. at 16–23. Some complaints reported more than one abusive tactic.

61. Rick Jurgens & Robert J. Hobbs, supra note 2, at 4–6.

62. Federal Reserve, Consumer Credit November 2014 Federal Reserve Statistical Release (2014), http://www.federalreserve.gov/RELEASES/g19/20150108/g19.pdf (“Consumer credit outstanding” includes most short- and intermediate-term credit extended to individuals, excluding loans secured by real estate).

63. Id.

64. CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2, at 7–8.

65. Id.

66. See id. (describing the growth of the debt buyer industry).

67. Federal Trade Commission, The Structure and Practices of the Debt Buying Industry ii, 23 (2013), http://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/structure-and-practices-debt-buying-industry/debtbuyingreport.pdf [hereinafter FTC Debt Buying Report] (reporting that, in a study of debt buyers conducted by the FTC, debt buyers paid an average of 4 cents per dollar of debt face value).

68. Id. at ii–iv.

69. Id.

70. Federal Trade Commission, Collecting Consumer Debts: The Challenges of Change iv (2009), https://www.ftc.gov/sites/default/files/documents/reports/collecting-consumer-debts-challenges-change-federal-trade-commission-workshop-report/dcwr.pdf [hereinafter Challenges of Change]. For example, debt collectors can “easily and relatively inexpensively mass-produce and send letters to debtors,” and “use sophisticated automated dialing and interactive voice recording technologies to efficiently place telephone calls to consumers.” Id.

71. Jessica SilverGreenberg & Edward Wyatt, U.S. Vows to Battle Abusive Debt Collectors, N.Y. Times (July 10, 2013), http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2013/07/10/usvowstobattleabusivedebtcollectors/.

72. Ann Carrns, Consumer Watchdog Takes Up Debt Collection, N.Y. Times (Nov. 8, 2013), http://www.nytimes.com/2013/11/09/your-money/consumer-watchdog-takes-up-debt-collection.html. See also Robert J. Hobbs, National Consumer Law Center, Comment Letter on Proposed Rules and Regulations Implementing the Telephone Consumer Protection Act of 1991 (Apr. 13, 2006), https://ecfsapi.fcc.gov/file/6518333643.pdf (observing that “consumers generally carry their cell phones with them in places where they would not want to receive a debt collection call: their car, the bus, a restaurant” and that “[c]aller identity information may now be faked and some debt collectors are using these deceptive services to make debt collection calls to a consumer with a relative’s, employers, or neighbor’s phone number appearing as the caller’s identity[,]” thereby depriving consumers of the freedom to decline to answer an unwanted debt collection call).

73. Press Release, Federal Trade Commission, FTC Brings First Case Alleging Text Messages Were Used in Illegal Debt Collection Scheme (Sep. 25, 2013), https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2013/09/ftc-brings-first-case-alleging-text-messages-were-used-illegal. In this action, a California-based debt collection company paid a $1 million settlement after the FTC found it had sent consumers text messages in which the company failed to disclose it was a debt collector, falsely portrayed itself as a law firm, falsely threatened to sue consumers or garnish their wages if the consumers did not pay. Id.

74. Challenges of Change, supra note 70, at 39–42 (noting that “debt collectors using newer technologies may inconvenience or embarrass consumers by contacting them while they are driving, at appointments, or at work,” but stating that debt collectors should be permitted to contact consumers on their mobile phones provided that they have previously obtained the consumers’ express consent to do so).

75. Jurgens & Hobbs, supra note 2, at 3–4.

76. Id.

77. Id.

78. Id.

79. McCollough v. Johnson, Rodenburg & Lauinger, L.L.C., 637 F.3d 939, 945–947 (9th Cir. 2011).

80. Order re: Judgment at 19, McCollough, 645 F. Supp. 2d 917 (No. 1:07-cv-00166).

81. Claudia Wilner & Nasoan Sheftel-Gomes, Debt Deception: How Debt Buyers Abuse the Legal System to Prey on Lower-Income New Yorkers 8 (2010), http://www.neweconomynyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/DEBT_DECEPTION_FINAL_WEB-new-logo.pdf (stating that, in survey of debt collection cases brought by debt buyers between January 2006 and February 2008, 81.4% ended in default judgment for the debt buyer, and another 12.9% ended in settlement, even though more than half of consumers who settled cases expressed doubts about the validity or amount of the debt).

82. New Economy Project, The Debt Collection Racket in New York: How the Industry Violates Due Process and Perpetuates Economic Inequality 6 (2013), http://www.neweconomynyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/DebtCollectionRacketUpdated.pdf. In New Jersey, court judgments in debt collection cases have skyrocketed from 500 suits in 1996 to 140,000 suits in 2008, and debt buyers account for nearly half of these lawsuits. ProPublica, So Sue Them: What We’ve Learned About the Debt Collection Lawsuit Machine (May 5, 2016), https://www.propublica.org/article/so-sue-them-what-weve-learned-about-the-debt-collection-lawsuit-machine. In Texas in 2007, “suits on debt” accounted for 43.8% of civil cases filed in county-level courts statewide, and for more than 78% of civil cases filed in county-level courts in Dallas County. Mary Spector, Debts, Defaults and Details: Exploring the Impact of Debt Collection Litigation on Consumers and Courts, 6 Va. L. & Bus. Rev. 257, 273 (Fall 2011). In Massachusetts in 2005, more than 60% of civil cases were brought by debt collectors. Beth Healy, A Debtor’s Hell: Part 2, A Court System Compromised, Boston Globe (July 31, 2006), http://www.boston.com/news/special/spotlight_debt/part2/page1.html.

83. See FTC Debt Buying Report, supra note 67, at 12–16 (reporting that in New York City in 2008, 26 debt buyers filed a deluge of cases in New York City Civil Court and won 94% of the lawsuits. Only ten percent of the alleged debtors responded to a summons and complaint and only 1 percent had legal representation. A lawyer from a New York City legal services organization explained that, due to improper service, many consumers are simply unaware of debt collection lawsuits filed against them).

84. New Economy Project, supra note 82, at 3. For example, in a survey of debt collection cases brought by debt buyers between January 2006 and February 2008, the vast majority ended in default judgment (81.4%) or settlement (12.9%), but in the remaining 5.7% of cases, the suits were discontinued or dismissed. Wilner & Sheftel-Gomes, supra note 81, at 8–9. The debt buyers in the sample did not win a single case on the merits. Id.

85. See 15 U.S.C. § 1692(e) (stating that one of the purposes of the FDCPA is “to insure that those debt collectors who refrain from using abusive debt collection practices are not competitively disadvantaged. . .”).

86. Bremner, supra note 39, at 1564 (“[A]busive debt collectors gain a competitive advantage from their coercive tactics.”). See also Lauren Goldberg, Dealing in Debt: the High Stakes World of Debt Collection After FDCPA, 79 S. Cal. L. Rev. 711, 716–17 (2006) (describing history of debt collection and noting that “[v]icious tactics were so effective that reputable companies found it hard to compete with ‘rogue agencies’”).

87. I.R.C. § 61(a). See also Comm’r v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426, 431 (1955) (holding that income includes all “undeniable accessions to wealth, clearly realized, and over which taxpayers have complete dominion.”).

88. Treas. Reg. § 1.611(a).

89. Comm’r v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. at 432; Michael B. Bogdanow, Taxation of Judgments and Settlements, Meehan, Boyle, Black & Bogdanow, P.C. (Apr. 2004), http://www.meehanboyle.com/taxation-of-judgments-and-settlements/.

90. I.R.C. § 104(a)(2).

91. See Comm’r v. Schleier, 515 U.S. 323, 329–331 (1995) (describing the tax consequences of a damage award arising from a hypothetical automobile accident).

92. Treas. Reg. § 1.104-1(c)(1) (as amended in 2012); H.R. Rep. No. 104-737, at 301 n.56 (1996) (Conf. Rep.), 1996–3 C.B. 741, 1041 (“[It] is intended that the term emotional distress includes symptoms (e.g., insomnia, headaches, stomach disorders) which may result from such emotional distress”). See also Blackwood v. Comm’r, 104 T.C.M. (CCH) 27, *3 (2012) (“[T]he fact that a taxpayer suffers physical symptoms from emotional distress does not automatically qualify the taxpayer for an exclusion from gross income under section 104(a)(2)”).

93. See Banaitis v. Comm’r, 340 F. 3d 1074, 1080 (9th Cir. 2003).

94. See Comm’r v. Banks, 543 U.S. 426, 431 (2005) (resolving controversy among circuit courts and holding that, when a litigant’s recovery constitutes taxable income, such income includes the portion of recovery paid to the litigant’s attorney as a contingent fee); National Consumer Law Center, Fair Debt Collection § 2.1.4 (5th ed. 2004) (consumer law manual, published in 2004, shortly before the Banks decision, discussing the uncertainty surrounding the circuit split over the income taxation of attorney’s fees awarded on a contingency basis); Fair Debt Collection Supplement § 2.1.4 (2005 supplement to the 2004 manual explaining that Banks unfavorably resolved the confusion).

95. 543 U.S. at 430.

96. Id. (citing Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e to 2000e-17).

97. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (“In any action or proceeding under this subchapter the court, in its discretion, may allow the prevailing party, other than the Commission or the United States, a reasonable attorney’s fee (including expert fees) as part of the costs[.]”).

98. Banks, 543 U.S. at 431.

99. Id. at 431–32.

100. Id. at 438–39.

101. Id. at 433 (citing Lucas v. Earl, 281 U.S. 111 (1930); Commissioner v. Sunnen, 333 U.S. 591 (1948); Helvering v. Horst, 311 U.S. 112 (1940)).

102. Id. at 434–438.

103. Id. at 438–439.

104. Id.

105. Id. at 439.

106. Id.

107. Id. at 438.

108. Id.

109. See Part V(A) for further discussion of the viability of this argument.

110. See Sinyard v. Commissioner, 268 F.3d 756, 759 (9th Cir. 2001), aff’g. 76 T.C.M. (CCH) 654 (1998); Vincent v. Commissioner, 89 T.C.M. (CCH) 1119 (2005) (attorney’s fees awarded pursuant to a fee shifting statute or regulation must be included in the gross income of the plaintiff where the awards are in lieu of contingency-fee); Sanford v. Commissioner, 95 T.C.M. (CCH) 16188 (2008); Green v. Commissioner, 93 T.C.M. (CCH) 917 (2007). However, the I.R.S. has indicated that there are at least some exceptions to the general rule that attorney’s fees constitute income. In two Private Letter Rulings, the IRS has found that attorney’s fees awarded to lawyers representing a client on a pro bono basis are not includable in the client’s gross income. I.R.S. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 2015-52-001 (Dec. 24, 2015); I.R.S. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 2010-15-016 (Apr. 16, 2010); Pro Bono Client Did Not Have Income from Attorney’s Fees Awarded to Counsel, 112 J. Tax’n 380 (2010) [hereinafter Pro Bono Client]. See Part V(B)(2) for further discussion of the Private Letter Rulings and their implications.

111. I.R.C. § 63(d); Cf. I.R.C. § 212 (“there shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year— (1) for the production or collection of income”). Expenses incurred for the production of income are just one category of expense that can be deducted below-the-line. Other examples of below-the-line deductions include trade or business expenses, I.R.C. § 62(a)(1), and charitable contributions, I.R.C. § 170.

112. I.R.C § 212(1).

113. See Gregg D. Polsky, A Correct Analysis of the Tax Treatment of Contingent Attorney’s Fee Arrangements: Enough with the Fruits and the Trees, 37 Ga. L. Rev. 57, 57–67 (describing how IRC §§ 67, 68 and the Alternative Minimum Tax limit the benefits of deducting an attorney’s fee award as a miscellaneous itemized deduction, such that the plaintiff’s tax liability is greater under the “inclusion and deduction” method than it would have been if it was simply excluded from income altogether).

114. Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 603; Robert W. Wood, Can Tax Rules Cut Legal Bills?, 82 N.Y. St. B. Ass’n J. 64, 64–65 (2010) [hereinafter Wood, Can Tax Rules Cut Legal Bills?]; Susan A. Bernson, The Taxation of Tort Damage Awards and Settlements: When Recovering More for a Client May Result in Less, 78 J. Kan. B. Ass’n 21, 22 (2009). Each of these limitations will be described in greater detail in infra Part III(B)(1).

115. See I.R.C. § 56(b)(1)(E) (stating that “[t]he standard deduction under section 63(c) . . . shall not be allowed” in computing alternative minimum taxable income).

116. See I.R.C. §§ 21(a), 22(d), 25A(d), 32(a) (describing that each of these credits is calculated based on adjusted gross income).

117. See infra Part III(B)(3) (describing the general policy justifications for limiting below-the-line deductions and explaining why those justifications don’t apply in the context of FDCPA attorney’s fees).

118. Michael J. Graetz & Deborah H. Schenck, Federal Income Taxation: Principles and Policies 228 (6th ed. 2009).

119. Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 353.

120. I.R.C. § 62(a) (“For purposes of this subtitle, the term “adjusted gross income” means, in the case of an individual, gross income minus the following deductions . . . ”); Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 353.

121. See Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 353 (“Gross Income (§ 61) minus Above the Line Deductions (§ 62(a)) equals Adjusted Gross Income (§ 62)”).

122. I.R.C. § 63; Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 353.

123. I.R.C. § 63(c).

124. § 63(d).

125. §§ 63, 151. All taxpayers are entitled to a personal exemption deduction for themselves and each of their dependents, regardless of whether they itemize deductions or take the standard deduction. Klein, Bankman, Shaviro & Stark, supra note 18, at 353. In 2015, the personal exemption amount was $4,000. I.R.S. Rev. Proc. 2014-61.24, Personal Exemptions (Nov. 17, 2014). The personal exemption, like itemized deductions, is subject to the “phaseout” provision of section 68. I.R.C. §§ 68, 151(d)(3). See infra Part III(B)(2) for further discussion of the phaseout provision.

126. I.R.C. § 63(b).

127. I.R.C. § 165(c)(3).

128. § 170.

129. § 212.

130. See id. (“In the case of an individual, there shall be allowed as a deduction all the ordinary and necessary expenses paid or incurred during the taxable year—(1) for the production or collection of income. . . .”); Boris I. Bittker & Lawrence Lokken, Federal Taxation of Income, Estates and Gifts ¶ 75.2, 1997 WL 439902, at *16 (2015).

131. I.R.C. § 63(b). For the 2015 tax year, the standard deduction was $6,300 for individuals, $12,600 for married couples filing jointly, and $9,250 for heads of household. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .14 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

132. For example, a taxpayer filing as an individual in 2015 is entitled to a standard deduction of $6,300. If the total value of a tax payer’s attorney’s fee award plus any other itemized deductions is less than $6,300, it is in her best interest to take the standard deduction of $6,300 rather than itemizing her deductions. By doing so, however, she loses the opportunity to deduct the value of the attorney’s fee award. Since she would have been able to take the $6,300 regardless of whether she received an attorney’s fee award, this puts her at a disadvantage, because she is not able to deduct the value of the attorney’s fees from her income.

133. See I.R.C. § 56(b)(1)(E) (stating that “[t]he standard deduction under section 63 (c) . . . shall not be allowed” in computing alternative minimum taxable income).

134. See Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 422–23 (describing the justifications for the standard deduction).

135. I.R.C. § 67(a); Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 256.

136. § 67(b); Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 255–56. Some of the excluded deductions are the itemized deductions for interest, casualty losses, and charitable donations. Id.

137. For the 2015 tax year, the applicable amounts under § 68(b) are $309,900 in the case of a joint return or a surviving spouse, $284,050 in the case of a head of household, $258,250 in the case of an individual who is not married and who is not a surviving spouse or head of household, $154,950 in the case of a married individual filing a separate return. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .14 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

138. See infra Part III(C)(1), for an example of such a taxpayer.

139. I.R.C. § 68(a)(1).

140. § 68(a)(2). The “amount of the itemized deductions otherwise allowable” includes all of the taxpayer’s itemized deductions minus three exceptions: deductions for medical expenses, investment interest, and losses incurred due to casualty, theft, or business. § 68(c).

141. I.R.C. § 55(a).

142. Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 776.

143. Id. See infra, Part III(C)(1) for an example of an AMT computation.

144. I.R.C. §§ 55(b)(2)(A), 56(b)(1), 67(b). Attorney’s fees are deducted as an expense incurred “for the production or collection of income,” § 212(1), and are thus included as a “miscellaneous itemized deduction” under § 67(b). Miscellaneous itemized deductions are added back in during the calculation of alternative minimum taxable income. For a critique of the AMT’s treatment of attorney’s fees, see Brant J. Hellwig & Gregg D. Polsky, Litigation Expenses and the Alternative Minimum Tax, 6 Fla. Tax Rev. 899 (2004).

145. I.R.C. § 32(a).

146. § 21(a).

147. § 22(d).

148. § 25A(d).

149. I.R.C. §§ 21(a), 22(d), 25A(d), 32(a).

150. Id.

151. § 32(a)–(b); See also Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .06, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

152. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746, http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

153. Id.

154. The Earned Income Tax Credit, Child Tax Credit, and other credits are important resources for working-poor individuals and families and are widely heralded as mechanisms for reducing poverty, promoting work, and generally increasing the well-being of low-income families. See generally Chuck Marr, Chye-Ching Huang, Arloc Sherman & Brandon Debot, Ctr. for Budget & Policy Priorities, EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds (Updated Oct. 1, 2015), http://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/6-26-12tax.pdf (describing the benefits of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Child Tax Credit).

155. See Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 258 (citing Boris Bittker, Income Tax Deductions, Credits and Subsidies for Personal Expenditures, 16 J.L. & Econ. 193, 203–04 (1973)).

156. See id.

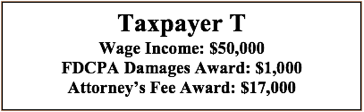

157. Id.

158. See Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 258–61. For this reason, employer-reimbursed business expenses (which are arguably more verifiably business-related) are deducted above-the-line, whereas unreimbursed business expenses are generally deducted below-the-line and are subject to a variety of limitations. See id. at 255.

159. I.R.C. § 212.

160. 15 U.S.C. § 1692k(a)(3) (“[I]n the case of any successful action to enforce the [FDCPA], [the plaintiff is awarded] the costs of the action, together with a reasonable attorney’s fee as determined by the court”).

161. See infra Part IV(B) (describing the “private attorney general” function of individual FDCPA lawsuits).

162. See James R. Hines Jr & Kyle D. Logue, Understanding the AMT, and Its Unadopted Sibling, the AMxT, 6 J. Legal Analysis 367, 369 (2014) (noting that “[t]he AMT makes it possible for Congress to adopt a regular income tax that has two attributes that have long been fundamental aspects of the U.S. tax system: progressive tax burdens and preferential tax treatment of certain activities.”); Staff of the Joint Comm. on Taxation, 108th Cong., Description of Revenue Provisions Contained in The President’s Fiscal Year 2005 Budget Proposal 8 (Comm. Print 2004) (“One of the basic tenets of tax policy is that an accurate measurement of ability to pay taxes is essential to tax fairness.”).

163. Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 776.

164. Martin J. McMahon & Lawrence A. Zelenak, Federal Income Taxation of Individuals ¶ 21.03 (2d ed. 2014) (citing Explanatory Material Concerning Committee on Finance 1990 Reconciliation Statement, 136 Cong. Rec. S15,632, S15,711 (Oct. 18, 1990)). Arguably, this goal could be better accomplished by simply adjusting marginal tax rates. Id.

165. Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 776.; Mcmahon & Zelenak ¶ 45.01 (3d. ed. 2016).

166. Abusive debt collection practices are highly concentrated in low- and moderate-income communities and communities of color, having deleterious effects on entire communities. Wilner & Sheftel-Gomes, supra note 81, at 10, http://www.neweconomynyc.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/DEBT_DECEPTION_FINAL_WEB-new-logo.pdf. According to a 2010 study, 91% of people sued by debt buyers and 95% of people with default judgments entered against them lived in low- or moderate-income communities. Id.

167. See infra Part IV(B) (describing the “private attorney general” function of the FDCPA).

168. See Allan J. Samansky, Nonstandard Thoughts about the Standard Deduction, 1991 Utah L. Rev. 531, 533 (1991) (noting that, when Congress enacted the standard deduction, “[p]robably its only purpose was simplification”).

169. See supra Part III(B)(2) (describing the tax consequences of a taxpayer’s choice between itemizing deductions and taking the standard deduction). Cf. Samansky, supra note 168, at 555 (noting that the standard deduction “increases the extent to which arbitrary factors determine federal income tax liability and generally deprives low and middle income persons of any benefits from itemized deductions”).

170. See, e.g., Victor Fleischer, 8 Tax Loopholes that the Obama Administration Could Close, N.Y. Times, Feb. 18, 2015, http://dealbook.nytimes.com/2015/02/18/8-tax-loopholes-the-obama-administration-could-close/ (describing loopholes such as the carried interest loophole, earnings stripping, and an unduly expansive definition of real estate); Ben Steverman, The Six Weirdest Tax Loopholes, Bloomberg Businessweek (Feb. 12, 2015), http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-02-12/the-six-weirdest-tax-loopholes (describing, for example, the grantor retained annuity trust, which allows individuals to place assets into a trust in exchange for an annuity payment, and any growth in the assets above the payment goes to their heirs tax-free).

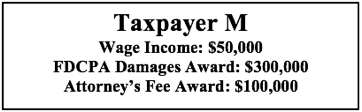

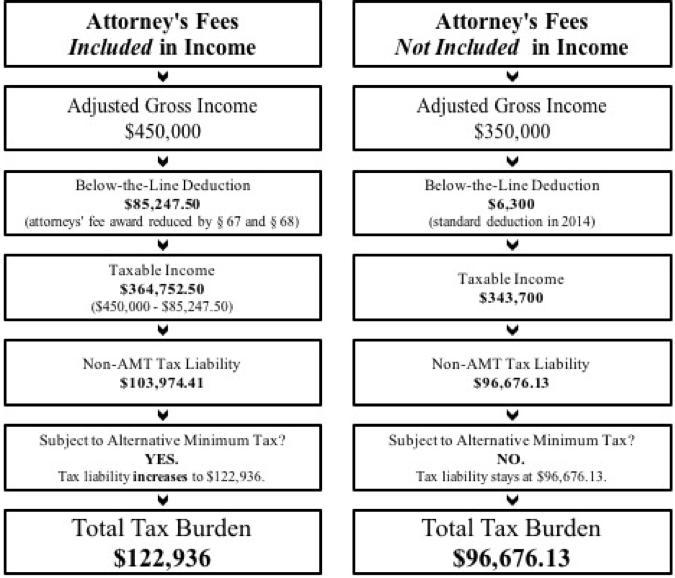

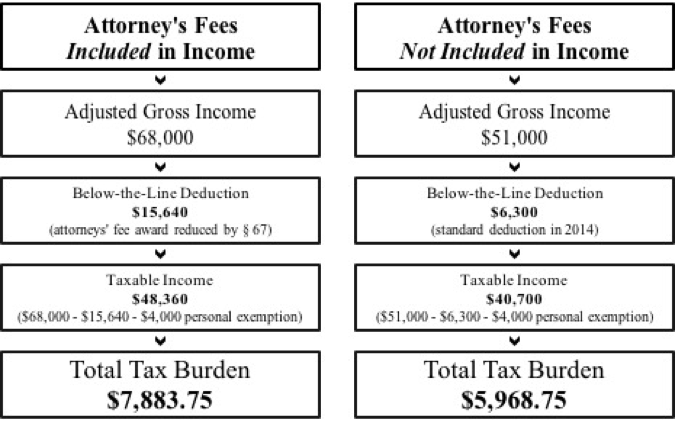

171. I use hypothetical plaintiffs rather than actual individuals because individual tax liabilities vary widely based on factors such as wages, marital status, and number of dependents, which are not publicly reported in conjunction with FDCPA awards. In crafting the wages of my hypothetical plaintiffs, I chose the round, easily-calculable figure of $50,000 that closely approximates the United States’ median household income of $53,657 in 2014. Carmen DeNavas-Walt & Bernadette D. Proctor, U.S. Census Bureau, Income & Poverty in the United States: 2014 (Sept. 2015), http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p60-252.pdf.

172. See supra notes 75–81 and accompanying text.

173. See supra notes 53–56 and accompanying text.

174. Order re: Judgment at 19, McCollough, 645 F. Supp. 2d 917 (No. 1:07-cv-00166).

175. See Polsky, supra note 113, at 63–64 (describing a similar hypothetical in the context of an employment discrimination lawsuit).

176. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .14 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

177. I.R.C. § 212(1).

178. See I.R.C. § 63(b) (providing that taxpayers may elect either to take the standard deduction or to take itemized deductions); M loses out on the $6300 because she has no other deductions she would normally itemize, so the standard deduction is like a “bonus” that is now inapplicable. In actuality, any taxpayer who chose to itemize would be able to deduct at least a small amount in either sales taxes or state and local income taxes paid during the tax year. Internal Revenue Service, Tax Guide 2015 For Individuals 148 (2015), https://www.irs.gov/publications/p17/ch22.html#en_US_2015_publink1000173147. For M and T (the second hypothetical plaintiff example, discussed infra at Part III(C)(2)) however, the amount of sales taxes or state and local income taxes is still significantly lower than the standard deduction, because they would be calculated for a person who typically earns $50,000 in wages. This caveat has been left out of the hypotheticals for the sake of simplicity.

179. See I.R.C. § 67(b) (defining miscellaneous itemized deductions); § 212(1) (allowing a deduction for expenses incurred in the production of income).

180. I.R.C. § 67(a).

181. I.R.C. § 68(a).

182. Charles S. Hartman, Missed it by that Much: Phase-Out Provisions in the Internal Revenue Code, 22 Dayton L. Rev. 187, 188 (1996) (“Section 68 [of the I.R.C.] functions as a phase-out of itemized deductions, but does not contain the term ‘phaseout.’”; as a general matter, “a phase-out is a provision in the Internal Revenue Code requiring a particular attribute of the taxpayer’s return to be reduced because of the size of some other number.”)

183. See Polsky, supra note 113, at 64–65 (discussing an example of a taxpayer whose attorney’s fee deductions were restricted by § 68).

184. Internal Revenue Service, Revenue Procedure 2014-61 13–14 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

185. I.R.C. § 68(a)(1). The “excess” of adjusted gross income over the applicable amount is equal to M’s adjusted gross income ($450,000) minus the applicable amount ($258,250), for an excess of $191,750. Three percent of that excess is equal to $5752.50.

186. § 68(a)(2). M would ordinarily be entitled to a deduction of $91,000, eighty percent of which is $72,800.

187. If her attorney’s fees were not included in M’s income, her taxable income would have been $343,700 ($350,000 minus the $6300 standard deduction). Hence, under the regular tax system, she is being taxed on an additional $15,300 of income despite the itemized deduction.

188. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .15 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. See also I.R.C. § 1(c). In 2015, single taxpayers with a total taxable income over $189,300 but not over $411,500 were subject to a tax rate of $46,075.25 plus 33% of the excess over $189,300. Id.

189. The term “tax liability” means the amount of tax that a taxpayer has to pay. Black’s Law Dictionary 1690 (10th ed. 2014) (defining “tax liability” as “[t]he amount that a taxpayer legally owes after calculating the applicable tax; the amount of unpaid taxes.”).

190. See I.R.C. § 55 (imposing the alternative minimum tax).

191. I.R.C. § 55(a).

192. I.R.C. § 55(d); Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .11 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

193. I.R.C. §§ 55(b)(2)(A), 56(b)(1), 67(b). Attorney’s fees are deducted as an expense incurred “for the production or collection of income,” § 212(1), and are thus included as a “miscellaneous itemized deduction” under § 67(b). Miscellaneous itemized deductions are added back in during the calculation of alternative minimum taxable income. § 56(b)(1).

194. Under § 55(d)(3), “[t]he exemption amount of any taxpayer shall be reduced (but not below zero) by an amount equal to 25 percent of the amount by which the alternative minimum taxable income of the taxpayer exceeds” $119,200 in 2015. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ 12 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. Thus, M’s exemption amount is to be reduced by $82,700, which is greater than the maximum exemption amount of $53,600. Therefore, M’s exemption amount is $0.

195. See I.R.C. § 55(b)(1)(A)(ii).

196. Under § 55(b), the tentative minimum tax is “26 percent of so much of the taxable excess as does not exceed $175,000,” plus “28 percent of so much of the taxable excess as exceeds $175,000,” adjusted for inflation. In 2015, the inflation-adjusted excess taxable income amount, above which the 28 percent tax rate applies, is $185,400. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ 12 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. Twenty-six percent of $185,400 is $48,204. M’s taxable excess exceeds $185,400 by $264,600, and twenty-eight percent of $264,600 is $74,088. M’s tentative minimum tax is equal to the sum of $48,204 and $74,088, which is $122,292.

197. I.R.C. § 55(a).

198. If M’s attorney’s fees had not been included in her adjusted gross income, she would not need to take any itemized deductions, so she would be able to take the standard deduction of $6300. See I.R.C. § 63(b) (providing that taxpayers may elect either to take the standard deduction or to take itemized deductions). She also takes a partial personal exemption of $1064, which, like the standard deduction, is subtracted from adjusted gross income. See I.R.C. §H§ 151 (allowing for personal exemption of the exemption amount to be deducted for the taxpayer); Internal Revenue Service, Personal Exemptions and Dependents (2015) [hereinafter “Personal Exemptions”], https://www.irs.gov/publications/p17/ch03.html#en_US_2015_publink1000309843. Unlike the standard deduction, the personal exemption is deducted from income even if the taxpayer itemizes her deductions. Id. The personal exemption is $4000 in 2015 but is phased out for single taxpayers whose adjusted gross incomes are above a certain amount, which is $258,250 for single taxpayers in 2015. Id. Single taxpayers must reduce the amount of their personal exemption by 2% for every $2500 of adjusted gross income above $258,250. Thus, M’s personal exemption is $1064 if attorney’s fees are not included in her income (when attorney’s fees are included in M’s income, her adjusted gross income is so high that she loses the personal exemption altogether). Taking both the standard deduction and the personal exemption into account, M’s taxable income would have been $342,636. Under the regular tax system, her income tax would have been $46,075.25 plus 33 percent of ($342,636 – $189,300). Internal Revenue Service, Revenue Procedure 2014-61 ¶ .15 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. See also I.R.C. § 1(c). Thus, her income tax is equal to the sum of $46,075.25 and $50,600.88, amounting to $96,676.13.

199. M’s tentative minimum tax is equal to twenty-six percent of $185,400 plus twenty-eight percent of so much of the taxable excess ($350,000) as exceeds $185,400. See Internal Revenue Service, Revenue Procedure 2014-61, 11 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. Thus, M’s tentative minimum tax is equal to $48,204 plus $46,088, which amounts to $94,292.

200. See Tolentino v. Friedman, 46 F.3d 645, 652-53 (7th Cir. 1995) (holding that market rate should be used in the calculation of attorney’s fees in an FDCPA case where the plaintiff only wins $1000 in statutory damages); Tolentino v. Friedman, No. 93 C 878, 1994 WL 125005, at *1 (N.D. Ill. Apr. 11, 1994), rev’d 46 F.3d 645 (7th Cir. 1995) (plaintiff requests $16,235 in attorney’s fees and $553.43 in costs). The Seventh Circuit remanded to the district court to determine the exact amount of attorney’s fees, but the attorney’s fee award probably amounted to something close to the attorney’s market-rate based estimate of $16,235 in attorney’s fees and $553.43 in costs.

201. See Polsky, supra note 113, at 63–64; Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746, ¶ 13 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

202. T’s “taxable excess” would be just $14,400, so her tentative minimum tax would be $3744. I.R.C. § 55(a), (b)(1)(A)(ii), (d).

203. I.R.C. § 212(1).

204. See I.R.C. § 63(b) (providing that taxpayers may elect either to take the standard deduction or to take itemized deductions).

205. See I.R.C. § 67(b) (defining miscellaneous itemized deductions); § 212(1) (allowing a deduction for expenses incurred in the production of income).

206. I.R.C. § 67(a).

207. T is not subject to § 68 because her adjusted gross income does not exceed the “applicable amount” of $258,250. See Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .13 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf.

208. If her attorney’s fees were not included in T’s income, her taxable income would have been $44,700 ($51,000 minus the $6300 standard deduction). Hence, under the regular tax system, she is being taxed on an additional $7660 of income despite the itemized deduction.

209. I.R.C. § 151; Personal Exemptions, supra note 198.

210. Rev. Rul. 2014-61, 2014-43 I.R.B. 746 ¶ .01 (2014), http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/rp-14-61.pdf. See also I.R.C. § 1(c). T’s tax rate is such because she is a single taxpayer with a total taxable income over $37,450 but not over $90,750. Id.

211. Based on an adjusted gross income of $51,000 ($50,000 in wages plus $1000 in statutory damages from her FDCPA victory) minus the standard deduction of $6300.

212. $5156.25 plus 25 percent of ($40,700 – $37,450).

213. In one of the leading pre-Banks decisions on the taxation of attorney’s fees awarded pursuant to a fee-shifting statute, the court contemplated the possibility that the tax liability for an attorney’s fee award would exceed the value of the plaintiff’s damages. Sinyard v. Commissioner, 268 F.3d 756, 760 (9th Cir. 2001) (“It is possible that where monetary recovery is little or nonexistent . . . , the attorneys’ fee award would leave the taxpayer owing more tax than anything he received in his . . . suit.”), aff’g. 76 T.C.M. (CCH) 654 (1998).

214. See infra Part IV(B).

215. See infra Part (V)(C)(5) (explaining that, before taking on an FDCPA case, attorneys should advise prospective clients of the potential tax consequences of bringing an FDCPA lawsuit).

216. See id.

217. Gonzales v. Arrow Fin. Servs., 660 F.3d 1055, 1067 (9th Cir. 2011) (“Statutory damages under the FDCPA are intended to ‘deter violations by imposing a cost on the defendant even if his misconduct imposed no cost on the plaintiff.’”) (quoting Crabill v. Trans Union, L.L.C., 259 F.3d 662, 666 (7th Cir. 2001). See also Matthew R. Bremner, The Need for Reform in the Age of Financial Chaos, 76 Brook. L. Rev. 1553, 1597 (2011) (explaining that many FDCPA actions are brought for technical violations that cause consumers no actual harm); Carter, supra note 39 (describing FDCPA attorney who, instead of pursuing actual damages, induces debt collectors to settle cases for statutory damages plus attorney’s fees).

218. See infra Part (V)(C)(5).

219. See id.

220. S. Rep. No. 95-382, at 5 (1977).

221. Id. at 2–3.

222. Id. at 5.

223. See, e.g., Gonzales v. Arrow Financial Services, L.L.C., 660 F.3d 1055, 1061 (9th Cir. 2011) (“Though the Federal Trade Commission (“FTC”) is empowered to enforce the FDCPA, 15 U.S.C. § 1692l, Congress encouraged private enforcement by permitting aggrieved individuals to bring suit as private attorneys general.”); Tolentino v. Friedman, 46 F.3d 645, 651 (7th Cir. 1995), cert. denied, 515 U.S. 1160 (1995); Palo, supra note 12, § 3 (2013).

224. See infra Part II(B) (discussing actual damages under the FDCPA).

225. See Roots v. Am. Marine Liquidators, Inc., No. 0:12-CV-00602-JFA, 2012 WL 3136462, at *1 n.1 (D.S.C. Aug. 1, 2012) (“The Senate Committee noted that abusive debt collectors cause ‘suffering and anguish.’ S. Rep. 95–382, at 2 . . . . The Committee expressed concern about practices that take a primarily emotional toll, such as using ‘obscene or profane language, threats of violence, telephone calls at unreasonable hours, . . . [and] disclosing a consumer’s personal affairs to friends, neighbors, or an employer.’ Id.”); Crossley v. Lieberman, 90 B.R. 682, 692 (E.D. Pa. 1988) (citing Congress’ concern about emotional harms as a reason to give damages to plaintiffs for the emotional harms they suffered, notwithstanding state tort law rules governing emotional distress).

226. 15 U.S.C. § 1692(a).

227. Palo, supra note 12, at § 51.

228. Black’s Law Dictionary 1717 (10th ed. 2014).

229. See Fair Debt Collection, supra note 34, § 2.6.

230. Kenneth S. Abraham, The Forms and Functions of Tort Law 18 (4th ed. 2012).

231. See generally CFPB 2014 FDCPA Report, supra note 2; Rick Jurgens & Robert J. Hobbs, supra note 2; Better Business Bureau, They Deal In Billions: A BBB Study of the Debt Collection Industry, Its Soaring Growth and Problems for Consumers (2011), http://www.bbb.org/Storage/142/Documents/Bill%20Collector%20Study%20%28FINAL%20WITH%20CHANGES%29%2012%2027%202011.pdf; Carolyn Carter & Robert J. Hobbs, Nat’l Consumer Law Ctr, No Fresh Start: How States Let Debt Collectors Push Families into Poverty (2013), http://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/report-no-fresh-start-bw.pdf.

232. See Abraham, supra note 230, at 18.

233. See supra Part III(C).

234. See id.

235. See supra Part III(C)(2).

236. See supra notes 53–56 and accompanying text (discussing Tolentino v. Friedman, an example of an FDCPA case in which attorney’s fees greatly exceeded the damages award). Attorney’s fees are especially likely to exceed the value of FDCPA damages when an FDCPA plaintiff wins only the statutory damages award of $1000 and does not win any actual damages. See supra note 39 (discussing the frequency of and reasons for FDCPA awards that are limited to statutory damages).

237. Rubenstein, supra note 35, at 2130 (citing F.C.C. v. Nat’l Broad. Co., Inc., 319 U.S. 239, 265 n.1 (1943) (Douglas, J., dissenting)).

238. Id. at 2134.

239. Black’s Law Dictionary 1389 (10th ed. 2014).

240. Rubenstein, supra note 35, at 2150–51.

241. Id.

242. See Abraham, supra note 230, at 18 (describing the general deterrence function of damages).

243. See Jeremy A. Rabkin, The Secret Life of the Private Attorney General, 61 Law & Contemp. Probs. 179, 179, 195–96 (1998) (treating this definition with skepticism and noting that some categories of cases have a partisan motive rather than a true public service role).

244. Rubenstein, supra note 35, at 2147–48.

245. Id. See also Martin H. Redish, Class Actions and the Democratic Difficulty: Rethinking the Intersection of Private Litigation and Public Goals, 2003 U. Chi. Legal F. 71, 91 (2003) (favoring a fairly broad interpretation of the term and stating that individual compensatory lawsuits may “be categorized as private attorney general actions, because they may well have the incidental impact—perhaps even intended by the legislative creation of the private right—of exposing and punishing law violations”); Rabkin, supra note 243, at 199–202 (concluding that, for the category of cases that can be said to represent partisan interests, the Supreme Court has been “unwilling either to eliminate the [role of the] private attorney general or to license it openly”).

246. Ann K. Wooster, Annotation, Private Attorney General Doctrine—State Cases, 106 A.L.R. 5th 523 § 2[a] (2003).

247. Id. Federal courts are prohibited from awarding attorney’s fees unless they have explicit statutory authorization to do so, but state courts have the discretion to award attorney’s fees under the private attorney general doctrine. Id. (citing Alyeska Pipeline Service Co. v. Wilderness Society, 421 U.S. 240 (1975)).

248. See 121 Cong. Rec. 32,960 (1975) (statement of Rep. Annunzio) (introducing the then-named Debt Collection Practices Act and stating that the act will be enforced in part by “private Attorney General actions”).

249. Id.

250. Jacobson v. Healthcare Fin. Servs., Inc., 516 F.3d 85, 90–91 (2d Cir. 2008).

251. Id. at 96.

252. Graziano v. Harrison, 950 F.2d 107, 113 (3d Cir. 1991) (citing de Jesus v. Banco Popular de Puerto Rico, 918 F.2d 232, 235 (1st Cir. 1990). The Graziano court goes on to note that “several courts have required an award of attorney’s fees even where violations were so minimal that statutory damages were not warranted.” Id. (citing Pipiles v. Credit Bureau of Lockport, 886 F.2d 22, 28 (2d Cir. 1989); Emanuel v. American Credit Exchange, 870 F.2d 805, 808–809 (2d Cir. 1989); cf. de Jesus, 918 F.2d at 233–34). Hence, the attorney’s fee provision is not solely about securing individual recovery, but rather about promoting the public interest in FDCPA enforcement.

253. A variety of other consumer protection statutes, including the federal Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(3), and Electronic Fund Transfer Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1693m(a)(3), and state consumer protection laws, also have fee-shifting provisions akin to that of the FDCPA. The same policy arguments justifying the exclusion of FDCPA attorney’s fees as income would also apply to attorney’s fees awarded in other statutes with fee-shifting provisions.

254. In many contingency arrangements, a client agrees to pay her attorney a certain percentage of her recovery—say, 30 percent. When the client wins her lawsuit, she is taxed on the full value of her winnings even though 30 percent of it goes to her attorney. In FDCPA cases, however, an attorney for a winning plaintiff is entitled to an attorney’s fee award irrespective of whether the attorney and her client had a contingency agreement. Therefore, the client and her attorney could have a retainer agreement that did not require the client to pay her attorney in any circumstances, but the attorney would still be entitled to attorney’s fees under the FDCPA. In such circumstances, a court-ordered attorney’s fee award is not absolving the client of a debt to her attorney, because she did not owe her attorney anything in the first place.

255. See supra Part III(A).

256. Comm’r v. Banks, 543 U.S. 426, 438 (2005).

257. Id.

258. 89 T.C.M. (CCH) 1119.

259. 93 T.C.M. (CCH) 917, aff’d in part and rev’d in part, Green v. Comm’r, 312 F. App’x 929, 930–31 (9th Cir. 2009) (“We agree with the tax court that Marcia Green is required to pay income tax on statutory attorneys’ fees awarded under the California Fair Employment and Housing Act.”).

260. 95 T.C.M. (CCH) 1618 .

261. 58 F.3d 756 (9th Cir. 2001).

262. Sanford, 95 T.C.M. (CCH) at *4; Green, 93 T.C.M. (CCH) at *3–*4; Vincent, 89 T.C.M. (CCH) at *5.

263. Sinyard, 268 F.3d at 758.

264. Id. at 256 (citing Old Colony Trust Co. v. Commissioner, 279 U.S. 716, 729 (1929) (“The discharge by a third person of an obligation to him is equivalent to receipt by the person taxed.”)). Sinyard explicitly recognized the potential unfairness caused by the inclusion of attorney’s fees in income, 58 F.3d at 762–763, but stated that this was a problem that must be resolved by Congress, not the courts.

265. See Sanford, 95 T.C.M. (CCH) 1618.

266. See Sinyard, 268 F.3d at 759 (noting that plaintiffs “bound themselves to pay” their attorneys one-third of damages award, so attorney’s fee award made them “so much the richer”).

267. See I.R.S. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 2015-52-001 (Dec. 24, 2015); I.R.S. Priv. Ltr. Rul. 2010-15-016 (Apr. 16, 2010); See infra Part V(B)(2) (discussing a private-letter ruling in which the I.R.S. advised that a retainer agreement expressly waiving a client’s obligation to pay any attorney’s fees exempted the client from tax liability for attorney’s fees that might be awarded pursuant to the fee-shifting provisions of the FDCPA).

268. See infra Part V(C)(1) (describing characteristics of a retainer agreement that clarifies that the client has no obligation to pay attorney’s fees).

269. It may be possible to construe attorney-client relationships as partnerships such that attorney’s fees are taxed only to the attorney, and not to the client. See Robert W. Wood, Attorney-Client Partnerships With a Straight Face, 129 Tax Notes 355, 355-59 (2010) [hereinafter Wood, Attorney-Client Partnerships With a Straight Face] (arguing that attorneys and clients should structure their relationship as a partnership in order to avoid subjecting the client to tax liability for attorney’s fee awards). Under federal income tax law, partnerships assign their income proportionately among their partners according to their percentage interests in the partnership. Graetz & Schenk, supra note 118, at 515. See I.R.C. § 701 (“Persons carrying on business as partners shall be liable for income tax only in their separate or individual capacities.”). The partnership theory was treated skeptically in Banks, however. Comm’r v. Banks, 543 U.S. 426, 436 (2005) (“We further reject the suggestion to treat the attorney-client relationship as a sort of business partnership or joint venture for tax purposes. The relationship between client and attorney, regardless of the variations in particular compensation agreements or the amount of skill and effort the attorney contributes, is a quintessential principal-agent relationship”). Moreover, creating a partnership and filing taxes pursuant to a partnership arrangement is complex, and requires a partnership agreement, special forms, and special bookkeeping mechanisms. See Wood, Attorney-Client Partnerships With a Straight Face, supra, at 359 (listing the forms and requirements that attorneys and clients would need to attend to in order to pursue a partnership arrangement). Therefore, the partnership theory of attorney’s fees may cause more problems than it would solve, even if a court were to uphold its legality.

270. This theory was presented to the Banks court in an amicus brief filed by Professor Charles Davenport, but the court did not address it because it was not raised by the Banks taxpayers. Brief for Professor Charles Davenport as Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents at 3–12, Banks, 543 U.S. 426 (Nos. 03-892 and 03-907); Banks, 543 U.S. at 427–428 (“We are especially reluctant to entertain novel propositions of law with broad implications for the tax system that were not advanced in earlier stages of the litigation and not examined by the Courts of Appeals. We decline comment on these supplementary theories.”). Professor Davenport argued that tort claims are property, and the attorney’s fees awarded in the case are transaction costs necessary to the acquisition and/or disposition of such property. Brief for Prof. Davenport, supra, at 9 (“The fees were necessary to the acquisition of property, the causes of action, and the lawyers’ services disposed of this property by obtaining payment from the defendants in the civil lawsuits.”). As transaction costs, attorney’s fees would be offset against the proceeds from the lawsuit and thereby excluded from income. Brief for Prof. Davenport, supra, at 10; see also Helvering v. Union Pacific, 293 U.S. 282, 286–87 (1934) (holding that commissions paid in the sale of bonds has the effect of “reducing the capital realized,” and should therefore be excluded from net income). The Banks court showed interest in Prof. Davenport’s theory during oral argument, but the lawyer for the government argued that attorney’s fees do not constitute transaction costs because no asset is disposed of; the legal claim is never actually transferred to the defendant. Transcript of Oral Argument at 12–15, Banks, 543 U.S. 426 (No. 03-907).

271. See supra note 94.

272. See supra Part III(C)(2).

273. See id.

274. See Stephen Cohen & Laura Sager, Why Civil Rights Lawyers Should Study Tax, 22 Harv. Blackletter L.J. 1, 24 (2006) (explaining that civil rights lawyers should study tax in order to structure their clients’ relief so that it does not cause undesirable tax consequences).

275. American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, I.R.C. § 62(a)(20) (amending § 62 of the tax code to allow attorney’s fees awarded in discrimination lawsuits to be deducted from adjusted gross income).

276. American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, I.R.C. § 62(a)(21) (amending § 62 of the tax code to allow attorney’s fees awarded in whistleblower lawsuits to be deducted from adjusted gross income).

277. Robert W. Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees: Patchwork by Congress and the Courts Creates Uncertainty, 67 Mont. L. Rev. 1, 1–2 (2006) [hereinafter Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees]; see also Comm’r v. Banks, 543 U.S. 426, 439 (2005) (“[T]he amendment added by the American Jobs Creation Act redresses the concern for many, perhaps most, claims governed by fee-shifting statutes.”).

278. Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees, supra note 277, at 1–2.

279. See generally Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees, supra note 277.

280. 29 U.S.C. §§201–219.

281. Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees, supra note 277, at 9–13.

282. See generally Jody Freeman & David B. Spence, Old Statutes, New Problems, 163 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1, 8 (2014); Michael J. Teter, Gridlock, Legislative Supremacy, and the Problem of Arbitrary Inaction, 88 Notre Dame L. Rev. 2217 (2013) (explaining the harms caused by Congressional gridlock).

283. American Jobs Creation Act of 2004; I.R.C. § 62(a)(20)-(21); see Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees, supra note 277, at 1–2.

284. Wood, The Federal Income Taxation of Contingent Attorneys’ Fees, supra note 277, at 1–2. As Wood explains, “[s]uggesting that Congress acted only to save face might be an exaggeration. Nevertheless, it took many years for Congress to provide any relief on the tax treatment of attorneys’ fees. The provision that was finally passed as part of the Jobs Act had been proposed and re-proposed since 1999, when it was first introduced as the Civil Rights Tax Fairness Act of 1999. However, the issue cried out long before that for attention.” Id. at 2.

285. In addition to traditional modes of lobbying, advocates might be able to persuade Congress to act with a compelling media campaign that draws attention to this issue. For example, prior to the Jobs Act’s passage, an article about the adverse tax consequences of attorney’s fee awards in discrimination lawsuits was published in The New York Times. Adam Liptak, Tax Bill Exceeds Award to Officer in Sex Bias Suit, N.Y. Times (Aug. 11, 2002), http://www.nytimes.com/2002/08/11/us/tax-bill-exceeds-award-to-officer-in-sex-bias-suit.html. This article alone probably did little to tip the scales in favor of action, but one or more compelling editorials could be part of a broader strategy to raise public—and therefore, Congressional—awareness of the tax consequences of fee-shifting provisions.

286. See generally Laura Sager & Stephen Cohen, How the Income Tax Undermines Civil Rights Law, 73 S. Cal. L. Rev. 1075 (2000) (pre-Jobs Act article arguing for an amendment to the tax code to exclude discrimination-related attorney’s fees from income).

287. I.R.C. §7805(a).