Creating Meaningful Opportunities for Release: Graham, Miller and California’s Youth Offender Parole Hearings

Introduction

Beth Caldwell∞

This article presents findings from a study on the implementation of California’s new Youth Offender Parole Hearing law, which aims to provide juvenile offenders with meaningful opportunities to obtain release from adult prison. It contributes to the debate surrounding how to apply the “meaningful opportunity to obtain release” standard that the Supreme Court deliberately left open to interpretation in Graham v. Florida and, to some extent, in Miller v. Alabama. The Supreme Court’s recent opinion in Montgomery v. Louisiana reinforces the idea that juveniles who demonstrate that they are capable of change are entitled to release. The data contained in this Article was obtained by reviewing the transcripts of the first 107 Youth Offender Parole Hearings; this sample represents all but two of the Youth Offender Parole Hearings that took place between January 2014 and June 2014. In the first six months of the law’s implementation, juvenile offenders were found suitable for parole at younger ages than the general population. Further, youth offenders appeared to have a more realistic chance of being released under the new law. This reform is, at the very least, an important step towards offering juvenile offenders more meaningful opportunities to earn their release from prison. At the same time, it does not go far enough. After discussing some limitations of the law, this Article concludes by recommending guidelines that would provide youth offenders more meaningful opportunities for release in parole hearings.

I. Introduction

II. The Legal Landscape After Graham, Miller, and Montgomery

A. Who is Entitled to a Meaningful Opportunity for Release?

B. What is a Meaningful Opportunity for Release?

C. What Mechanism Should Be Used to Determine Whether an Individual Qualifies for Release?

i. California’s Specialized Parole and Resentencing Procedures

ii. Other Legislative Solutions

III. A Study of California’s Effort to Provide a “Meaningful Opportunity to Obtain Release”

A. S.B. 260: The Law and Its Implementation

B. Methods and Demographic Information

i. Grant Rate

ii. Age at Release

iii. Statistically Significant Factors

v. Weight of Disciplinary Infractions

vi. Risk Assessments

vii. Giving Great Weight to the Hallmark Features of Youth

IV. Key Components Rendering Release Opportunities More Meaningful

A. How Old Is Too Old?: Age at the Time of Parole

i. Meaningful vs. Geriatric Release

ii. State Laws

B. Likelihood of Obtaining Release

C. Access to Rehabilitative Programming

ii. California

iii. Expanding Access to Rehabilitative Programs

V. Recommendations for Youth-Specific Parole Hearings

A. The Crime Should Carry Less Weight Than an Individual’s Change and Maturation

B. Recent Positive Behavior Should Outweigh Previous Misconduct

C. Risk Assessments Should Be Designed to Properly Assess Juvenile Offenders

D. Suitability Factors Should Be Consistent with Adolescent Development Research

VI. Conclusion

Over the last decade, the Supreme Court has limited the imposition of extreme punishments for juveniles in a trilogy of Eighth Amendment cases: Roper v. Simmons, Graham v. Florida, and Miller v. Alabama.[1] In response, states across the country are grappling with how to live up to the Court’s newly established requirement that juvenile offenders sentenced to life in prison be provided with meaningful opportunities to obtain release.[2] In Graham, the Supreme Court purposefully left the definition of its new legal term of art—”meaningful opportunity to obtain release”—vague, explaining, “[it] is for the State, in the first instance, to explore the means and mechanisms for compliance.”[3] In his dissent, Justice Thomas predicted that this ambiguity “will no doubt embroil the Court for years,” pointing out that the majority opinion did not specify what “such a ‘meaningful’ opportunity entail[s],” when it must occur, and what principles parole boards must consider.[4]

Predictably, the “meaningful opportunity to obtain release” standard has continued to be a topic of much debate in state legislatures and courts. New legislation has been proposed and, in several states, enacted to provide more robust definitions of this rather vague standard.[5] At the same time, related issues are working their way through the courts. Just this year the Supreme Court decided that Miller applies retroactively.[6] Other questions, such as whether extremely long sentences should be treated as life without parole (“LWOP”), have led to splits of authority on key issues.[7] Due to these diverging interpretations at the state level, the Supreme Court will likely address questions about the scope and substance of the “meaningful opportunity” for release requirement in the coming years, as Justice Thomas predicted.[8]

This Article contributes to the national debate by analyzing the preliminary results of a new California law, designed to create more meaningful opportunities for juvenile offenders to be released through parole hearings. California Senate Bill 260 (“S.B. 260”) was passed in 2013 and went into effect on January 1, 2014. It provides opportunities for most juveniles sentenced in adult court to obtain release after serving between fifteen and twenty-five years in custody.[9] Informed by the Supreme Court’s decisions in Graham and Miller, the legislation created specialized Youth Offender Parole Hearings (“YOPHs”), in which the Board of Parole Hearings is required to “give great weight to the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to adults, the hallmark features of youth, and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of the prisoner in accordance with relevant case law.”[10]

California is at the forefront of a legislative trend to create specialized parole procedures for people who were sentenced to life—or to otherwise lengthy sentences—in adult court for crimes committed when they were under eighteen years old.[11] Following California’s lead, West Virginia, Massachusetts, and Connecticut have passed similar legislation.[12] Similar laws were also considered in Hawaii and Vermont, although the state legislatures passed more modest bills that prohibit the imposition of LWOP for juveniles but disregard resentencing options for juveniles sentenced to life with the possibility of parole or its equivalent.[13]

This is a critical yet under-examined topic. As Richard A. Bierschbach explained in a 2012 law review article, “despite an ever-expanding literature [discussing Graham], the significance of parole to the decision remains almost entirely unexplored.”[14] Since then, a small body of scholarship addressing parole and meaningful opportunities for release has emerged.[15] As the first empirical study on the implementation of legislation designed to expand release opportunities in light of Graham and Miller, this Article contributes concrete data to what has been a theoretical debate about the new standard’s meaning. Analyzing parole practices designed for juvenile offenders is particularly important given that the Supreme Court recently noted in Montgomery v. Louisiana that “[a] State may remedy a Miller violation by permitting juvenile homicide offenders to be considered for parole, rather than by resentencing them.”[16]

This Article presents the findings of a study that reviewed the parole suitability hearing transcripts of all but two YOPHs that were held during the first six months of S.B. 260’s implementation, from January through June of 2014.[17] Based on the study’s findings, I discuss aspects of the law that seem to be providing more meaningful opportunities for youth offenders to earn their release from prison.[18] I also address areas where S.B. 260 may be falling short of creating truly meaningful opportunities for release. Given that parole hearings are one of two ways states can respond to the Graham requirement for meaningful opportunities, this analysis is important and should inform future efforts to design parole procedures for juvenile offenders.[19]

In its first six months, S.B. 260 seems to have created more realistic opportunities for juvenile offenders to earn parole at younger ages. From January through June of 2014, “youth offenders,” defined in California as state prisoners under the age of eighteen at the time of their offenses, both qualified for parole hearings and were found suitable for parole at an average age nine years younger than other parole-eligible prisoners.[20] They were also more likely to be granted parole than their counterparts who committed crimes as adults.[21] This suggests that the Board of Parole Hearings (“BPH”) may be moving in the direction of offering juvenile offenders more realistic opportunities for release within a timeframe that would allow them to establish meaningful lives after prison. Requiring parole decision-makers to consider the hallmark features of youth may be increasing the likelihood of young offenders being released on parole. However, it is too early to draw conclusions regarding its long-term impact.

This Article proceeds in four parts. Part II begins by discussing the foundations of this doctrine from Graham and Miller, including various states’ responses to the Supreme Court’s requirements. It focuses on three major questions that have arisen in related academic discourse: (1) who is entitled to meaningful opportunities for release?; (2) what makes an opportunity for release meaningful?; and (3) what mechanisms should be used to determine whether an individual should be released? Part III summarizes the empirical study, beginning with an overview of S.B. 260 and the youth-specific parole hearings it created. It describes my research methodology, presents the demographic information of the sample, and concludes with a summary of the study’s major findings.

Parts IV and V discuss the implications of the study’s results. Part IV explores three core components that are essential for any parole system purporting to establish meaningful opportunities for release should address. These core components are: (1) the age of release; (2) the likelihood of obtaining release; and (3) the need for more rehabilitative options for youth offenders in prison. I also discuss the strengths and weaknesses of California’s model, using data from the study and incorporating relevant examples from other states’ approaches.

Part V discusses the importance of developing specialized standards that require decision-makers to appropriately consider the hallmark features of youth, and young offenders’ diminished culpability. It explores the specific areas these standards should address in order to render opportunities for release meaningful, using examples from the study to illustrate potential obstacles. Specifically, I argue that (1) parole-eligibility standards must place more weight on rehabilitation than on the circumstances surrounding a crime; (2) prison behavior must be viewed in the context of adolescent development principles; and (3) risk assessments must emphasize growth and maturity while incorporating expertise about adolescence.

II.The Legal Landscape After Graham, Miller, and Montgomery

When the Supreme Court ruled in Graham v. Florida that, pursuant to the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment, juveniles who have not committed homicide may not be sentenced to LWOP, it required the government to provide “a meaningful opportunity to obtain release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation.[22] Graham’s holding specifically applies to a discrete population of youth offenders—those under the age of eighteen who were not convicted of homicide and were sentenced to LWOP.[23]

The defendant in the case, Terrance Graham, was sixteen years old when he was convicted of attempted armed robbery and armed burglary after he entered a restaurant wearing a mask.[24] His accomplice hit the restaurant’s manager with a metal bar, causing a head injury that required stitches.[25] Although Graham was a juvenile at the time, he was charged as an adult[26] and, pursuant to a plea agreement, was sentenced to probation.[27] Shortly thereafter, he was found to be in violation of his probation for participating in a home invasion robbery.[28] At that point, the sentencing court imposed the maximum sentences for each of the original armed burglary and armed robbery charges, resulting in a life sentence. In Florida, a life sentence equated to LWOP because the state had abolished parole.[29]

While Graham’s specific holding limits the application of a “meaningful opportunity to obtain release” to an LWOP sentence for a non-homicide offense, the Court’s reasoning implies that all juvenile offenders should be entitled to meaningful opportunities to be released from prison.[30] The Court recognized that adolescents are fundamentally different from adults. It reasoned that “because juveniles have lessened culpability they are less deserving of the most severe punishments.”[31] The Court went on to discuss several key characteristics of adolescence that diminish young people’s culpability, including a “lack of maturity and an underdeveloped sense of responsibility,” “susceptib[ility] to negative influences and outside pressures, including peer pressure,” and “characters [that] are ‘not as well formed’” as those of adults.[32] It emphasized, “[f]rom a moral standpoint it would be misguided to equate the failings of a minor with those of an adult, for a greater possibility exists that a minor’s character deficiencies will be reformed.”[33] The “nature of juveniles”[34] is common to all adolescents, regardless of the sentence they receive or the crime they commit.[35]

In 2012, the Supreme Court applied this reasoning to a broader segment of the population in Miller v. Alabama, moving past Graham’s limited application to youth who had not committed homicide by reasoning that “none of what [Graham] said about children—about their distinctive (and transitory) mental traits and environmental vulnerabilities—is crime specific.”[36] In Miller, the Court considered two companion cases, both involving fourteen-year-olds who were convicted of murder and sentenced to LWOP.[37] Based on its conclusion that the hallmark features of youth are not crime specific, the Court emphasized that even young people convicted of murder have diminished culpability in comparison to adult offenders.[38] Ultimately, the Court held in Miller that the Eighth Amendment prohibits sentencing a juvenile to LWOP under a mandatory sentencing scheme that does not allow the court to consider mitigating information about the defendant’s youth.[39]

Like Graham, Miller’s reasoning contemplates the relationship between youth and criminal sentencing more broadly than its relatively narrow holding might imply. Miller reiterated Graham’s reasoning that “‘[a]n offender’s age’ … ‘is relevant to the Eighth Amendment,’ and so ‘criminal procedure laws that fail to take defendants’ youthfulness into account at all would be flawed.’”[40] The opinion explains that the “foundational principle” of Graham and Roper is that the “imposition of a State’s most severe penalties on juvenile offenders cannot proceed as though they were not children.”[41] According to the Supreme Court, the differences between juveniles and adults clearly are relevant to assessing which criminal punishments constitute cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment.

Most recently, the Supreme Court held in Montgomery v. Louisiana that Miller applies retroactively because it created a new substantive rule.[42] In Montgomery, the Court made clear that LWOP sentences for juveniles should be extremely rare. According to the Court, Miller “established that the penological justifications for life without parole collapse in light of the distinctive attributes of youth,” such that LWOP sentences violate the Eighth Amendment “for a child whose crime reflects unfortunate yet transient immaturity.”[43] Thus, according to Montgomery, “Miller determined that sentencing a child to life without parole is excessive for all but “the rare juvenile offender whose crime reflects irreparable corruption.”[44]

Further, Graham, Miller, and Montgomery set up a constitutional framework that requires young offenders—at least those whose most serious offense is not homicide, but arguably those convicted of homicide as well—to have “meaningful opportunities” to earn their release from prison.[45] Under Montgomery, “[t]he opportunity for release [on parole] should be afforded to those who demonstrate the truth of Miller’s central intuition—that children who commit even heinous crimes are capable of change.”[46] This “meaningful opportunity to obtain release” requirement has spawned debate in academic literature and in the courts regarding both its scope and substance.[47] This debate focuses on three major questions: (1) which juvenile offenders are entitled to meaningful opportunities for release; (2) what makes an opportunity meaningful; and (3) what mechanisms should be used to provide these opportunities. Courts and legislatures have been crafting new responses to these questions in recent years.

A. Who is Entitled to a Meaningful Opportunity for Release?

One central question in the debate concerns which juvenile offenders are entitled to meaningful opportunities for release.[48] Does the requirement apply only to those sentenced to LWOP, or does it extend to those sentenced to de facto LWOP sentences, such as determinate term-of-year sentences that exceed the defendant’s life expectancy? In an essay addressing several areas Miller left open for debate, Craig S. Lerner argues that Miller uses ambivalent language with respect to whether its holding applies only to “the harshest possible penalty” of LWOP or to “the most serious penalties,” which may “extend to long prison sentences.”[49] A predictable split of authority has arisen among the states with respect to this issue.

The California Supreme Court held that Graham prohibits de facto LWOP sentences, concluding that a 110-year sentence violated the Eighth Amendment because the juvenile offender in the case “would have no opportunity to ‘demonstrate growth and maturity’ to try to secure his release, in contravention of Graham’s dictate.”[50] In subsequent California cases, courts have used actuarial tables to estimate defendants’ life expectancies in order to assess whether a sentence equates to LWOP.[51] The Iowa Supreme Court has interpreted Graham to prohibit even shorter determinate sentences, concluding that term-of-years sentences that would render juvenile defendants eligible for parole at the ages of sixty-nine and seventy-eight are de facto LWOP sentences under Graham and Miller.[52]

Until the Florida Supreme Court resolved the issue in March of 2015, Florida courts were divided as to whether lengthy determinate sentences should be treated the same as LWOP sentences for purposes of applying Graham and Miller.[53] Some Florida appellate courts felt “compelled to apply Graham as it is expressly worded, which applies only to actual life sentences without parole.”[54] Other courts disagreed with this interpretation, concluding that sentences that exceed a defendant’s life expectancy “are the functional equivalent of a life without parole sentence and will not provide . . . a meaningful opportunity to obtain release.”[55] In Henry v. State and Gridline v. State, the Florida Supreme Court concluded that sentences of ninety-years and seventy-years for juvenile offenders who had not committed homicide do “not provide a meaningful opportunity for future release” and are therefore “unconstitutional in light of Graham.”[56]

In contrast, state courts in Georgia and Arizona, have concluded that Graham does not require meaningful opportunities for release for those sentenced to de facto life sentences.[57] Louisiana’s Supreme Court limited Graham’s application to LWOP cases, holding that a juvenile’s seventy-year sentence for a non-homicide offense, which would render him eligible for parole at the age of eighty-six, does not amount to a de facto LWOP sentence.[58] The Louisiana court found, “Graham’s holding . . . applies only to sentences of life in prison without parole, and does not apply to a sentence of years without the possibility of parole.”[59]

In addition to the debate over whether Graham and Miller apply to determinate sentences that effectively amount to LWOP sentences, there is also a question as to whether juveniles sentenced to life with the possibility of parole are entitled to meaningful opportunities to obtain release. Life sentences may offer the possibility of release, but this opportunity may not rise to the level of being “meaningful.” As Sarah French Russell argues, “[i]f the chance of release is not meaningful under a state’s existing parole system, then a sentence of life with parole is equivalent to an LWOP sentence for Eighth Amendment purposes.”[60]

Taken together, the reasoning in Graham and Miller would seem to require a meaningful opportunity to obtain release for all juvenile offenders regardless of their sentence or offense. In other words, those sentenced to lengthy term-of-years sentences and to life with the possibility of parole should be entitled to the same opportunities for release as those sentenced to the more extreme sentence of LWOP. It would be illogical for the Court to create a legal standard that gives those sentenced to the more serious sentence of LWOP a more realistic chance of release than those sentenced to life with the possibility of parole.[61] Furthermore, the Supreme Court seems to have anticipated that this requirement would apply to all life sentences. The Graham opinion specifically says that when a state “imposes a sentence of life it must provide . . . some realistic opportunity to obtain release before the end of that term.”[62] By referring to “a sentence of life” rather than “a sentence of life without parole,” the reasoning implies that Graham’s holding may reach beyond those sentenced to LWOP.

Several states have passed or are considering legislation that goes beyond the minimal requirements of Graham and Miller by creating procedures that offer juvenile offenders a greater likelihood of release after serving fewer years in custody.[63] This emerging trend is remarkable because it departs sharply from the trend towards more punitive juvenile justice legislation that emerged in the 1990s in response to unrealized fears about an increasingly dangerous population of juvenile “superpredators.”[64] The Supreme Court set the tone for this changing approach to juvenile justice, and the foundational principles emphasized by the Court now seem to be shaping state legislation.[65]

B. What Is a Meaningful Opportunity for Release?

The second major issue in the meaningful opportunity for release debate surrounds the substance of this new legal term of art. What does it mean to offer a “meaningful opportunity”? Further, what distinguishes a meaningful opportunity from a non-meaningful opportunity?

The Supreme Court deliberately left these questions open in Graham, explaining that “[it] is for the State, in the first instance, to explore the means and mechanisms for compliance.”[66] The Court was clear that release is not required.[67] Rather, the Eighth Amendment “forbid[s] States from making the judgment at the outset that those offenders never will be fit to reenter society.”[68] On the other hand, the opinion states that executive clemency, which would provide a “remote possibility” of release, “does not mitigate the harshness of the sentence” of life without parole.[69] In sum, a meaningful opportunity requires more than a “remote possibility” of release; the opportunity must be “realistic.”[70]

Predictably, states have interpreted this requirement differently: some have created narrow procedures that provide remote possibilities of release, while others have created more robust mechanisms to allow juvenile offenders to be re-sentenced or paroled.[71]

Most states have been (or will be) forced to change their sentencing laws to bring them in line with the minimum legal requirements of Graham and Miller.[72] Under the narrowest reading of Graham, LWOP is unconstitutional for juvenile offenders who have not been convicted of homicide, but a life sentence is constitutional as long as there is some process to consider release at some (potentially distant) point in the future. Under a narrow reading of Miller, an LWOP sentence may be constitutional for a juvenile offender convicted of homicide if: (1) it is not imposed under a mandatory sentencing scheme; and (2) the sentencing court considers mitigating evidence relating to the offender’s youth.[73]

In response to Graham, states that previously allowed LWOP for non-homicide offenders have been forced to eliminate this sentencing option.[74] Many states merely converted LWOP sentences to life sentences with the possibility of parole for juvenile non-homicide offenders.[75] The problem with this approach is that changing LWOP to a life sentence does not bring the law into compliance with Graham unless the states also offer truly “meaningful opportunit[ies] to obtain release” to those offenders.

After Miller, states with mandatory LWOP sentencing schemes for juveniles who had committed homicide were forced to revise their laws.[76] Many of these states brought their laws in line with Miller by giving judges the option to choose between LWOP and an alternative sentence.[77] In these jurisdictions, LWOP is still an option; the only difference after Miller is that judges have the choice between LWOP and life with parole, or between LWOP and a lengthy term-of-years sentence.[78]

Based on a narrow interpretation of the holdings of Graham and Miller, these legal reforms do create mere possibilities of release. However, they do not comport with the cases’ clear requirements that the opportunities afforded to youth offenders be both meaningful and realistic. By minimally shifting their sentencing schemes, these states ignore the fundamental principles underlying the Court’s recent jurisprudence on juveniles and the Eighth Amendment. Giving sentencing courts the discretion to choose whether to attach the possibility of parole to a life sentence does not adequately respond to the Eighth Amendment violations raised by imposing life sentences on juvenile offenders.

In contrast to the narrow approach described above, a number of states have passed legislation that goes further than what Graham and Miller explicitly require, by eliminating LWOP sentences for all juvenile offenders, including those convicted of homicide.[79] In addition to eliminating LWOP sentences for all juveniles, a growing number of states are creating specialized re-sentencing and parole procedures aimed at providing juvenile offenders more meaningful opportunities for release.[80] These more expansive reforms offer greater opportunities for incorporating the sprit of the Supreme Court’s recent jurisprudence into sentencing and parole law and are more consistent with the Supreme Court’s reasoning than the narrow, textual responses previously discussed.

C. What Mechanism Should Be Used to Determine Whether an Individual Qualifies for Release?

States have developed different procedures for complying with the Supreme Court’s mandates in Graham and Miller. Some have put the decision-making power in the hands of judges by creating mechanisms that allow people to petition for resentencing in court.[81] Others have vested this decision-making power with parole boards.[82] California has done both; courts have the decision-making power over resentencing juveniles originally sentenced to LWOP, whereas BPH has decision-making authority over those juveniles sentenced to life sentences, or to any determinative sentence that exceeds fifteen years.[83]

In addition to determining whether courts or parole boards should be responsible for deciding who qualifies for release, states must also decide whether to create special standards and procedures for decision-makers to follow in making these determinations. States have pursued different paths here as well. Some, like California, Florida, Massachusetts, Nebraska, and West Virginia, have created detailed standards that incorporate the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Graham and Miller into the decision-making process.[84] For example, Florida’s statute orders judges to consider the following factors in determining whether a juvenile offender has been rehabilitated and is therefore “fit to reenter society”:

(a) Whether the juvenile offender demonstrates maturity and rehabilitation; (b) Whether the juvenile offender remains at the same level of risk to society as he or she did at the time of the initial sentencing; (c) The opinion of the victim or the victim’s next of kin; (d) Whether the juvenile offender was a relatively minor participant in the criminal offense or acted under extreme duress or the domination of another person; (e) Whether the juvenile offender has shown sincere and sustained remorse for the criminal offense; (f) Whether the juvenile offender’s age, maturity, and psychological development at the time of the offense affected his or her behavior; (g) Whether the juvenile offender has successfully obtained a general educational development certificate or completed another educational, technical, work, vocational, or self rehabilitation program, if such a program is available; (h) Whether the juvenile offender was a victim of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse before he or she committed the offense; (i) The results of any mental health assessment, risk assessment, or evaluation of the juvenile offender as to rehabilitation.”[85]

In contrast, other states handle these cases using their existing procedural frameworks.[86]

i. California’s Specialized Parole and Resentencing Procedures

California was the first state to pass legislation creating specialized parole procedures designed to offer juvenile offenders meaningful opportunities for release from prison. In 2012, the state passed Senate Bill 9 (“S.B. 9”), which created a procedure for juveniles sentenced to life without parole to petition the courts for re-sentencing after serving twenty-five years in custody.[87] Following on the heels of S.B. 9, California passed S.B. 260 in 2013. This bill went much further than S.B. 9, transforming the state’s treatment of juvenile offenders by creating a specialized parole process for almost all juveniles who were sentenced to lengthy prison terms. It applies both to people sentenced to life and to those with long fixed term sentences.[88] Juvenile offenders become eligible for specialized YOPHs after they have served between fifteen and twenty-five years in prison, depending on the term of their original sentence.[89]

S.B. 260 incorporates the Supreme Court’s findings about adolescent development and the resulting diminished culpability of young offenders.[90] It requires that BPH “give great weight to the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to adults, the hallmark features of youth, and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of the prisoner in accordance with relevant case law.”[91]

This legislation was informed by the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence. The legislation began with the following recapitulation of some of the central themes in Miller v. Alabama:

The Legislature finds and declares that, as stated by the United States Supreme Court in Miller v. Alabama [citations omitted], “only a relatively small proportion of adolescents” who engage in illegal activity “develop entrenched patterns of problem behavior,” and “developments in psychology and brain science continue to show fundamental differences between juvenile and adult minds,” including “parts of the brain involved in behavior control.”[92]

The bill used language and reasoning from Graham and Miller to craft a law that applies to a much broader population than the Supreme Court requires. It provides virtually all juveniles sentenced as adults—regardless of sentence or offense—the opportunity to obtain release after serving twenty-five years in prison; many are eligible after serving fifteen or twenty years.[93] Specifically, S.B. 260’s purpose is “to establish a parole eligibility mechanism that provides a person serving a sentence for crimes that he or she committed as a juvenile the opportunity to obtain release when he or she has shown that he or she has been rehabilitated and gained maturity.”[94]

ii. Other Legislative Solutions

Nationwide, similar legislation has recently been proposed and enacted by several states. In March 2014, West Virginia passed legislation very similar to California’s S.B. 260.[95] The legislation was clearly informed by Graham and Miller. A previous version of the bill that was introduced in the Senate quotes several passages from Miller to highlight juveniles’ susceptibility to influence, as well as “developments in psychology and brain science [that] continue to show fundamental differences between juveniles and adult minds.”[96]

West Virginia’s legislation, like California’s, embraces the spirit of Graham and Miller. In addition to abolishing LWOP for juveniles, it establishes parole eligibility for all juveniles after they have served fifteen years of incarceration.[97] It directs the parole board to consider “the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to that of adults, the hallmark features of youth, and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of the prisoner during incarceration.”[98]

Similarly, in 2014, Massachusetts passed a bill that allows all young offenders convicted of murder to be eligible for parole after serving twenty to thirty years of their sentences.[99] The Massachusetts bill incorporates some interesting provisions to ensure that youthful characteristics are prioritized, including requiring at least two people who specialize in child psychology and mental development to be on a commission considering the use of “developmental evaluations” in parole hearings.[100]

In February 2014, Hawaii passed legislation that banned LWOP for juvenile offenders.[101] It too began with a paragraph reiterating the key findings on adolescent development and the diminished culpability of youth from the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence.[102] The original bill not only eliminated LWOP as a sentencing option for juveniles, but also would have established a process for sentencing modification after a juvenile had served either ten years in prison or the statutory minimum for the offense.[103] However, this portion of the bill was ultimately stricken from the version that passed.[104]

Connecticut enacted a law in June 2015 creating specialized parole hearings for juvenile offenders.[105] Now, all juvenile offenders in Connecticut will have the opportunity to be released on parole after serving between twelve and thirty years in prison.[106]

Legislation in this area is evolving rapidly. Nineteen states passed related legislation between 2012 and 2015.[107] Fourteen states no longer allow LWOP as a sentencing option for juveniles.[108] The “meaningful opportunity to obtain release” issues are a hot topic in both state legislatures and the courts.[109] Given the contested nature of this issue, the following analysis of California’s newly implemented legislation is particularly timely.

III.A Study of California’s Effort to Provide a“Meaningful Opportunity to Obtain Release”

California has been on the cutting edge of implementing legislative and judicial reforms that respond to the spirit of the Supreme Court’s decisions in Graham and Miller. The remainder of this Article presents data about the first six months of the implementation of California’s YOPHs and analyzes this data in the context of pre-existing academic discourse on the topic.

Graham’s meaningful opportunity for release is operationalized in most states by their parole systems.[110] Eligibility for a parole hearing has been referred to as the “distinguishing factor” between constitutional and unconstitutional sentences.[111] Under Graham, LWOP sentences are unconstitutional for non-homicide juvenile offenders, while adding the possibility of parole arguably renders a life sentence constitutional.[112] Under Miller, a mandatory life sentence would not violate the Constitution as long as parole is a possibility.[113] Therefore, examining parole hearing procedures and outcomes for juvenile offenders sentenced to life is critical to understanding the real-world impacts of Graham and Miller.

Despite the central importance of parole hearings in this area of the law, academic examinations of the issue are scarce.[114] Similarly, the Supreme Court did not provide guidance on the requirements of parole hearings in Graham or Miller. However, its holdings are essentially toothless if youth offenders are processed through parole hearings that do not offer realistic opportunities to earn release.[115]

A. S.B. 260: The Law and Its Implementation

California S.B. 260 followed California S.B. 9, a 2012 law that created a mechanism for resentencing juvenile offenders with LWOP sentences.[116] However, S.B. 260 is much broader than S.B. 9; it applies to almost all juveniles sentenced as adults, rendering them eligible for parole after they have served between fifteen and twenty-five years in custody.[117] It draws on the spirit and reasoning of Graham and Miller but goes farther than the Supreme Court requires. S.B. 260 is, in the words of some advocates, a “game changer” because it creates an opportunity for parole for virtually all juveniles sentenced in adult court. Extending the law to apply to those juveniles sentenced to determinative terms—lengthy sentences that are not “life” sentences—expanded the law’s reach dramatically. Whereas there are approximately 2,623 juvenile offenders serving life sentences in California,[118] an estimated 6,500 California people in California prisons qualify for YOPHs under S.B. 260.[119]

Those sentenced to determinative term-of-years sentences, regardless of the length of the sentence, are eligible for parole after serving fifteen years in custody, which includes time spent in juvenile hall and jail facilities.[120] People sentenced to life terms of less than twenty-five years to life are eligible for release after serving twenty years, and those with sentences of twenty-five years or more to life are eligible for parole after serving twenty-five years.[121] Those who were originally sentenced to LWOP may petition to have their sentence reduced to a twenty-five year to life sentence under the procedures set out in S.B. 9.[122] This requires petitioning the sentencing court for a resentencing hearing that considers, among other things, mitigating characteristics relating to the individual’s youth at the time of the crime and evidence of rehabilitation while in prison.[123] If the court sentences the youth offender to twenty-five years to life, he then becomes eligible for a parole hearing under the procedures S.B. 260 sets forth for those with a twenty-five to life sentence.[124] Under this schema, virtually every juvenile offender has an opportunity to obtain release after serving twenty-five years.[125]

There are four exceptions that disqualify certain juvenile offenders from the YOPH process.[126] First, anyone sentenced to a third strike is not eligible.[127] Second, a juvenile offender is also ineligible if, after turning eighteen-years-old, he commits an additional crime where malice aforethought is a necessary element of the offense or where a life sentence is imposed.[128] Crimes that include malice aforethought as a necessary element include murder, attempted murder, and assault with a deadly weapon by a prisoner.[129] Third, people sentenced to LWOP are not eligible unless they are resentenced to twenty-five years to life under the process outlined in S.B. 9.[130] Finally, people convicted of a sex offense subject to a life sentence under California’s “one strike” law are excluded.[131]

In addition to creating an accelerated timeline for parole hearings for youth offenders, S.B. 260 established specialized standards and procedures the parole board must follow in YOPHs. For example, BPH officers must meet with inmates six years prior to their initial YOPH eligibility date in order to “provide the inmate information about the parole hearing process, legal factors relevant to his or her suitability or unsuitability for parole, and individualized recommendations for the inmate regarding his or her work assignments, rehabilitative programs, and institutional behavior.”[132] This is a chance for people to learn about the steps they should take to prepare for their parole hearings.

Most importantly, YOPHs are supposed to be different than other parole hearings because BPH is required to give “great weight” to “the diminished culpability of juveniles as compared to adults, the hallmark features of youth, and any subsequent growth and increased maturity of the prisoner in accordance with relevant case law.”[133]

Like other California parole hearings, they take place on site at the prisons where the individuals are housed and are generally conducted by a Commissioner and a Deputy Commissioner.[134] There are seventeen Commissioners in the state, each appointed by the governor.[135] A District Attorney usually participates in the hearing to oppose parole. In California, all inmates are entitled to counsel at parole hearings, and the state provides attorneys for those who would not otherwise be represented.[136] However, the state compensates attorneys a maximum $400 per case; experienced parole attorneys assert that preparing for a parole hearing in a competent manner requires far more time than a $400 payment would allow for.[137]

B. Methods and Demographic Information

This study examines the first six months of the implementation of California’s law. It tracks the quantitative outcomes of all 144 YOPHs that were scheduled between January 1, 2014—the date the law went into effect—and June 30, 2014. Moreover, it analyzes the qualitative content of 107 of the 109 YOPHs that were conducted during this timeframe. BPH was unable to provide complete transcripts for two of the hearings, which is why two were left out of the transcript-review portion of the study.

Information about the hearings was gathered from three primary sources: (1) YOPH schedules posted on California’s BPH website on a monthly basis; (2) Parole Suitability Hearing Results lists published on the BPH website on a weekly and monthly basis; and (3) individual transcripts from all of the YOPHs that were held, which are available to the public and were requested from BPH on an individual basis. The lists of scheduled hearings were cross-referenced against the hearing results lists in order to identify which hearings were postponed and which were actually held. With the assistance of a team of research assistants, I then requested the transcripts of all hearings that were conducted during this time period.

Based on a preliminary review of twenty transcripts, I designed an online database including sixty fields to code information contained in the individual transcripts. Transcripts range in length from 100 to over 200 pages. Fields included demographic data such as the inmate’s age at the time of the crime and age at the time of the hearing. The database also tracked the prison where the hearing was held and the names of the Commissioners charged with making the decisions. Other important fields included a description of the offense, information about any childhood abuse, the number (and nature) of disciplinary infractions, and whether the prisoner is identified as a prison gang member.

The database also included some open-ended questions to allow researchers to capture information that did not neatly fit into another field. For example, researchers were asked whether anything else stood out from the transcript; they were also asked to include any comments made about the inmate’s emotions and to summarize the reasons the Commissioners provided for their decision. Six research assistants read through transcripts entered information into the database. I reviewed all of the entries by comparing them to the transcripts, making corrections as needed.

One hundred and forty-four YOPHs were scheduled between January 1 and June 30, 2014. Of the 144 hearings scheduled within these six months, 109 were conducted and thirty-five were postponed.[138] Out of the thirty-five postponed hearings, eleven were stipulations whereby the prisoner stipulated that he was not suitable for parole. Twenty-four others were postponed for other reasons, without an admission of unsuitability for parole.[139]

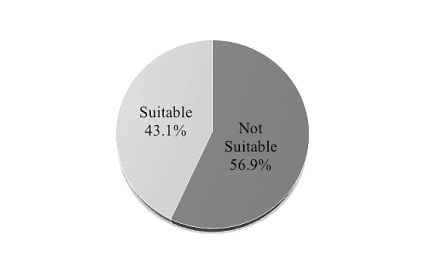

Out of the 109 hearings that were held during this six-month period, forty-seven were granted (43.1%); sixty-two were denied (56.9%).[140] However, that is not the end of the story. In California, the Governor has the power to reverse the decisions of BPH for people convicted of homicide. Although previous California governors typically reversed almost all parole grants for people convicted of murder, California’s current governor Jerry Brown allows most parole decisions to stand. In 2014, he reversed twenty percent of BPH’s decisions overall; this number includes YOPHs in addition to all other parole hearings.[141] Out of the forty-seven grants for youth offenders in the sample, Governor Brown reversed eleven, at a rate of twenty-four percent.[142] Overall, thirty-five men were released under S.B. 260 in its first six months.

Results of YOPH Hearings, January 1, 2014-June 30, 2014

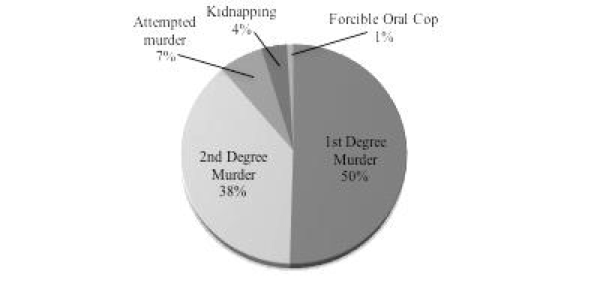

All of the people who had YOPHs during this six-month period were male. They were housed in twenty-two different prisons across the state. Most were committed to state prison for murder convictions. Only twelve were sentenced to life for crimes other than homicide: seven for attempted murder, four for kidnapping, and one for forcible oral copulation.[143] Of those convicted of murder, fifty-four were for first degree murder and forty-one for second degree. They were all incarcerated for indeterminate life terms ranging from seven-to-life to thirty-six-to-life, meaning that the BPH and the Governor have the power to determine whether they will ever be released from prison.

Most Serious Commitment Offense

Some of these prisoners were convicted of multiple offenses arising out of the same event. Over seventy-five percent committed crimes against only one victim. In addition to the one case where the most serious offense committed was forcible oral copulation, five additional individuals were convicted of rape or forcible oral copulation in addition to murder, attempted murder, or kidnapping. Out of the entire sample, 5.5% were convicted of one of these two sex offenses.

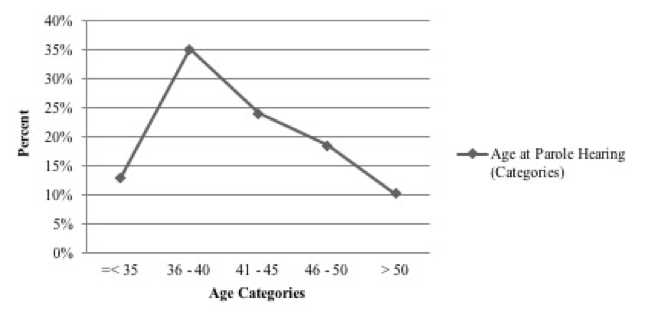

All of the individuals in the sample were under eighteen years of age when they committed their offense. One was fourteen, seven were fifteen years old, forty-two were sixteen, and fifty-seven were seventeen at the time they committed the crimes that resulted in the life sentence. They had served an average of 24.7 years in custody, ranging from twelve to forty-three years. They ranged in age from twenty-nine to sixty-three at the time of their parole hearings; the average age was forty-two, with a median of forty-one years old. Most had been to previous parole hearings, although twenty-one had never had a parole hearing before.

Age at Parole Hearing (Categories)

Thirty percent of the sample had been involved with prison gangs according to information contained in the suitability hearing transcripts, although that association may have been in the past.

Reliable information about the race of the potential parolees was not available from the BPH website or the parole hearing transcripts I obtained, so data is lacking in this area. This is a particularly important area for future research given the entrenched nature of racial disparities in the criminal justice arena.[144] In California, there are 2,623 juvenile offenders serving life sentences.[145] Of the juvenile lifers, 31.5% are Black, 11.7% are White, and 45.2% are Hispanic.[146] The impact of race on parole suitability decisions under S.B. 260 is a critical issue that I hope to be able to obtain more information about in the future.

The following section presents the study’s major findings. When possible, as in the case of the grant rate, I compare the results of the YOPHs to results of California parole hearings for adult offenders within the same time period. However, much of the comparison data would only be available by coding the transcripts of adult offenders within the same time period, a task beyond the scope of this study. In an effort to draw some comparisons between YOPHs and parole hearings for the general population, I occasionally draw upon a study of California parole hearings conducted by Robert Weisberg, Debbie A. Mukamal, and Jordan D. Segall of the Stanford Criminal Justice Center.[147] Their research includes detailed information derived from reviewing 448 parole hearing transcripts from hearings conducted in 2009 and 2010.[148] I use their data from 2010 as a rough point of comparison throughout this section.[149]

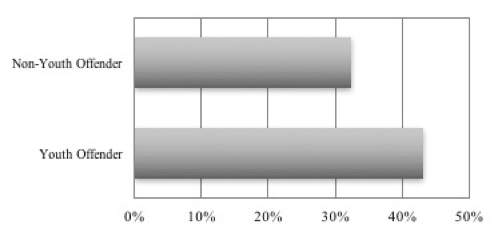

i. Grant Rate

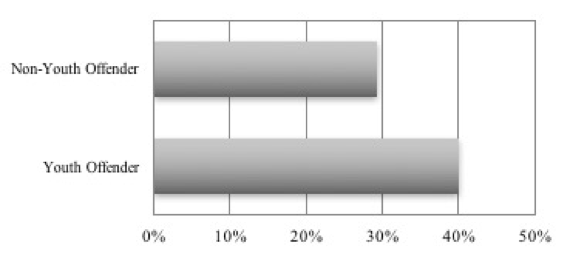

In its first eleven months, S.B. 260 created at least marginally more meaningful opportunities for release given that youth offenders were released at a higher rate than non-youth offenders during the same time period.

The law went into effect on January 1, 2014, and the first youth offender parole hearing took place on January 7 of the same year.[150] Two hundred and sixty hearings were scheduled in the first eleven months of 2014. In nineteen of these hearings, the prisoner stipulated to being unsuitable for parole.[151] Putting aside these nineteen stipulations, 241 hearings were actually held. One hundred and four people were found suitable, while 137 were found unsuitable for parole, equating to a grant rate of 43.15%.

In contrast, the grant rate for California parole hearings (excluding YOPHs) during that same period—from January through December of 2014—was 32.33%. Thus the grant rate for youth offenders over the first year of the program was approximately eleven percent higher than for non-youth offenders. During this time period, youth offenders were statistically more likely to be found suitable than adult offenders.[152] This finding is statistically significant at the 0.01 level.

Percentage of Parole Hearings Resulting in a Finding of Suitability, Including Stipulations to Parole Unsuitability[153]

January 1 – November 30, 2014

Percentage of Parole Hearings Resulting in a Finding of Suitability, Excluding Stipulations to Parole Unsuitability[154]

January 1, 2014 to November 30, 2014

These numbers are based on the first eleven months of S.B. 260’s implementation. I chose to analyze the first eleven months rather than limit these numbers to the six months I focus on in the transcript-review portion of the study because this larger sample allows for greater reliability.[155] It is important to keep in mind that this data is preliminary and that results may change substantially as S.B. 260 is implemented more broadly.[156]

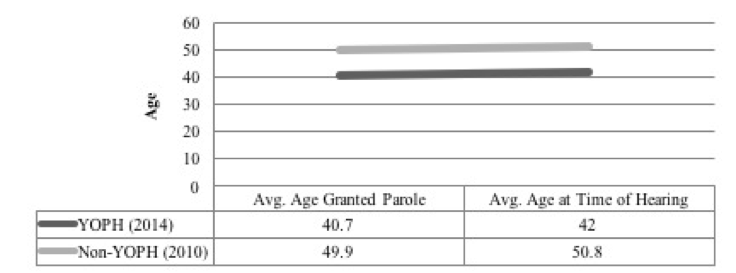

ii. Age at Release

In the sample, YOPHs resulted in opportunities for release at a younger age. In the first six months of S.B. 260’s implementation, youth offenders who were granted parole had an average age of 40.7, which is 9.2 years younger than the average age of lifers who were granted parole in California in 2010.[157] This is consistent with the younger age at which people qualify for YOPHs; the average age of people who had YOPHs in this six-month period was forty-two, which is 8.7 years younger than the average age of prisoners serving life terms who had parole hearings in 2010, which was 50.8 years old.[158]

Age Comparison: YOPH and Non-YOPH

This preliminary data regarding the decreased age at which people qualified for parole is one indication that S.B. 260 may be creating more meaningful opportunities for people to be released because younger people will have more time to build meaningful lives outside of prison.

Over time, the age gap will probably widen between youth offenders and the general parole-eligible population because this preliminary data is skewed for two reasons. First, the only people scheduled for parole hearings during the time of this study were people with life sentences. Under the different timeframes for parole eligibility established by S.B. 260, people with life sentences must serve twenty to twenty-five years in order to be eligible for parole, unless they would otherwise be eligible for parole earlier. However, those with determinate term-of-years sentences qualify after a shorter period of time—fifteen years. Thus, as California begins to hold YOPHs for people who qualify after serving fifteen years in custody, the average age at the time of release for youth offenders may decrease.[159]

In the first six months of S.B. 260’s implementation, no hearings for people serving determinative sentences were held, so this population is not represented in this sample. Second, the average age may decrease because some of the people currently being scheduled for YOPHs did not have the opportunity to qualify for release under these new standards at the twenty-five year mark and have thus served more time before their initial suitability hearings. S.B. 260 renders juvenile lifers eligible for parole after twenty-five years even if they otherwise would not have qualified for parole for many more years. For example, an inmate serving fifty-years to life would have otherwise had to serve forty-two years in prison before being eligible for release; S.B. 260 shaves seventeen years off of the initial suitability hearing date. Since this is a new law, many are having their first YOPH after serving longer than twenty-five years in prison. Over time, as people are considered at the fifteen, twenty, or twenty-five year marks of their sentences, the average age at the time of release should decrease for youth offenders.

iii. Statistically Significant Factors

I tested the following variables using a logistic regression analysis to determine whether they were statistically significant predictors of the outcomes of the YOPHs in the sample: age at time of offense; age at parole hearing; presence of the victim/next of kin at the hearing; presence of a juvenile record; whether the crime was committed with others; any history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse of the prisoner; cumulative number of disciplinary infractions; number of years since last disciplinary infraction; prison gang involvement; number of victims of the crime; whether this was the initial hearing; the rating of the risk assessment; what the most serious commitment offense was; and whether the prisoner committed rape or forcible oral copulation as part of the commitment offense.

According to the logistic regression analysis, only four of these variables were statistically significant predictors as to whether the outcome of a hearing would be suitable or not suitable. These were: (1) age at time of offense; (2) cumulative number of disciplinary infractions; (3) number of years since last disciplinary infraction; and (4) risk assessment rating. The remaining variables were not statistically significant in predicting the outcome of the hearings.

In some respects, these findings are similar to the results of the Stanford study, which tracked the outcomes of California parole hearings in 2010. Like the Stanford study, the number of victims of the crime, the commitment offense, and the presence of a prior juvenile record were not statistically significant variables.[160]

A test of the full model against a constant only model was statistically significant, indicating that the predictors as a set reliably distinguished between suitable and not suitable outcomes (chi square = 71.387, p < .000 with df = 14). Nagelkerke’s R2 of .694 indicated a moderately strong relationship between prediction and grouping. Prediction success overall was eighty-nine percent (91.9% for Not Suitable and 84.2% for Suitable). The Wald criterion demonstrated that number of years since last disciplinary infraction, risk assessment rating, and whether the inmate had committed rape or forcible oral copulation in the commitment offense made significant contributions to prediction (p < .050). The remainder predictors were not significant predictors.

California parole hearings generally begin with a review of “pre-commitment factors” relating to life experiences that occurred prior to the offense for which the prisoner is serving life. BPH Commissioners typically address the individual’s childhood, previous criminal history, and circumstances that contributed to the prisoner’s criminality in this portion of the hearing.

For S.B. 260 hearings, I expected that challenges during the prisoners’ childhoods, such as experiences with abuse, would help to explain their law-breaking behavior as teenagers and would therefore impact the suitability determination. Although the transcripts indicated that sixty-six of the 107 youth offenders (61.7%) had experienced physical, sexual, and/or emotional abuse during their childhoods, this was not a statistically significant predictor of the outcome of the hearing.

Seventy-five percent of the individuals in the sample had a prior juvenile record of delinquency, but the presence or absence of a juvenile record was also not statistically significant. This is notable because under California’s Factors Governing Parole Suitability and Unsuitability, the presence of a juvenile record that includes violence is a factor that points towards unsuitability, and the lack of a juvenile record points towards suitability.[161] However, using one’s juvenile record as a reason to find an inmate unsuitable for parole conflicts with S.B. 260’s emphasis on growth and maturation since the time of the crime. The fact that this variable was not significant may indicate that BPH is giving more weight to the prisoner’s more recent behavior rather than using a historic juvenile record as a reason to deny parole.

An individual’s age at the time of the commission of the commitment offense was statistically significant in this study. Younger ages were correlated to higher suitability rates. This may indicate that Commissioners find it easier to see the influence of the hallmarks of youth and their diminished culpability in younger offenders than in their older peers.

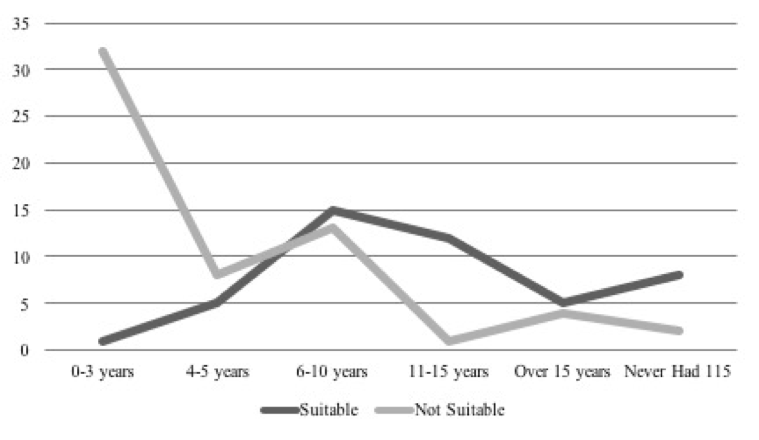

v. Weight of Disciplinary Infractions

Of the 107 individuals in this sample, most had received at least one disciplinary infraction under section 115 of Title 15 of California’s Code of Regulations during their time in prison. Nine of the 107 (8.4%) had never been issued a disciplinary infraction. Most had between one and ten on their records, with sixteen individuals receiving more than twenty over the course of their prison careers.

This study indicates that BPH has been willing to consider change over time with respect to disciplinary infractions in YOPHs thus far. While the majority of those granted release have fewer than five section 115 infractions on their records, seven people with ten or more infractions were found suitable, including individuals with nineteen, twenty, and twenty-two infractions on their records. A closer review of the individual transcripts of these three cases indicates that in each, BPH noted that the disciplinary infractions were not recent. This is one indication that BPH may be giving more weight to young offenders’ growth and development over time rather than focusing on a cumulative total.

Number of Years Since Last Disciplinary Infraction

Similarly, the data shows that the length of time since the last disciplinary infraction seems to be more important than the total number of infractions on an individual’s record. In fact, the length of time since the last disciplinary infraction is the single most important predictive variable tracked in this study.[162] For each additional year that an individual went without obtaining a disciplinary infraction, he was 1.31 times more likely to have been found suitable.[163]

However, an individual’s cumulative total of disciplinary infractions was still found to be one of four statistically significant variables correlated to the outcome of the YOPH according to a logistic regression analysis. Total number of section 115 infractions was significant at the .001 level, indicating that there is a relationship between one’s overall disciplinary history and the likelihood of being found suitable for parole. Nine of those found suitable had zero disciplinary infractions, and eight had only one infraction. On the other hand, nineteen of the forty-seven who were found suitable had more than five infractions on their records, amounting to 40.4% of those found suitable. Forty-nine out of the sixty who were found unsuitable (81.7%) had more than five disciplinary infractions on their records. Thirty percent of those in the sample with more than five disciplinary infractions were found suitable, which differs from the results of the 2010 Stanford study where only eleven percent of those with more than five disciplinary infractions were granted parole.[164]

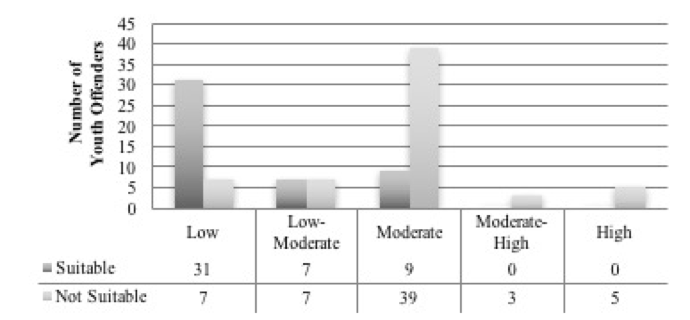

vi. Risk Assessments

In California, as in many other states, psychologists prepare Risk Assessment reports that are submitted to the parole board assessing a prisoner’s suitability for parole.[165] California uses the Compas rating test to weigh a variety of factors and to predict an individual’s risk of future violence. With respect to this sample of youth offenders, the vast majority were found to present a low (38.0%), low/moderate (13.8%), or moderate (44.0%) risk of violence if released. Only eight of the 107 were rated a moderate/high or high risk.

The rating on the risk assessment was one of the four statistically significant predictors found in the logistic regression analysis. Within this sample, parole was more likely to be granted for those with a low or low/moderate risk assessment. Thirty-one out of thirty-eight inmates with a low risk assessment and seven out of fifteen inmates with a low/moderate risk assessment were found suitable for parole. Similar to the Stanford study, no one with a moderate/high or a high risk assessment was found suitable. One notable difference appears to be for those ranked with a moderate risk assessment. Out of forty-nine inmates ranked “moderate” in the Stanford study, only two were found suitable whereas out of forty-nine ranked moderate in the Youth Offender sample, nine were found suitable.

YOPH Risk Assessment Ratings

vii. Giving Great Weight to the Hallmark Features of Youth

In the YOPH transcripts reviewed in this study, the Commissioners consistently acknowledged that the hallmark features of youth must be given great weight under the law, but it is unclear whether these hallmark features actually impacted their decisions. One or more hallmark features of youth were recognized even among ninety percent of the cases where parole was denied. The presence of hallmarks of youth in cases where parole was denied may indicate that the Commissioners are not giving the “great weight” that S.B. 260 requires to these characteristics.

For example, seventy-three percent of the sample committed their commitment offense with at least one other person, and susceptibility to influence is one of the key hallmarks of youth. However, this variable did not have a statistically significant predictive value, indicating that it may not be given “great weight” in practice.

BPH Commissioners justified denying parole even when they recognized hallmark features of youth due to two primary factors. In ninety-six percent of the denials where hallmark features of youth were acknowledged, Commissioners explained that they found the diminished culpability of these offenders outweighed by either (1) prison misconduct or (2) a lack of insight, remorse and/or honesty about the offense. Two of the cases appeared to have been denied due to an inmate’s mental health issues rather than these other considerations.

In sum, a prisoner’s age when the crime was committed, their disciplinary history while in prison, and the risk assessment rating were predictors of parole suitability, while the presence of hallmark features of youth were not. This indicates that decision-making in YOPHs may not differ significantly from other parole hearings. One of the key contributions of S.B. 260 was to require the hallmark features of youth be given “great weight,” so the fact that this variable does not appear to be having a statistically significant outcome on suitability determinations indicates that S.B. 260 may not be functioning as intended. I analyze some of the reasons behind this problem, and some possible solutions based on other states’ models, in the remainder of this Article.

IV.Key Components Rendering Release Opportunities More Meaningful

This Part analyzes the study’s findings in relation to three areas that are essential to crafting truly meaningful opportunities for release: (1) a person’s age at the time of parole eligibility; (2) the likelihood of obtaining release; and (3) opportunities for rehabilitation in prison. In each of these areas, S.B. 260 does not seem to be having as strong an impact as it should in order to render these opportunities for release truly meaningful. I discuss the study’s findings on each of these topics in the national context in order to highlight the need for improvement in California’s model for YOPHs.

A. How Old Is Too Old?: Age at the Time of Parole

In order for an opportunity for release to be meaningful, it should occur within a timeframe that would allow the individual to live a meaningful life outside of prison. Being released at a younger age opens more doors to obtaining an education, building a career, and having a family. But how does this reasoning translate into numbers? When must an opportunity for release be available in order for it to be meaningful?

As reported in Part II, members of this study’s sample were released at an average age of 40.7, which is 9.2 years younger than the average age at which other California lifers were found suitable for parole. On the one hand, the fact that youth offenders are being paroled nearly a decade earlier than their adult offender counterparts is an indication that their age at the time of release allows them more meaningful opportunities to move on with their lives. On the other hand, this timeframe still forecloses many possibilities in people’s lives. It is unclear whether people incarcerated in their teenage years and paroled in their early forties will be able to establish meaningful careers, family relationships, and friendships after release. In order to be meaningful, release should be available in a timeframe that does not foreclose these opportunities. For women, the possibility of having children is limited at this age, and the same would hold true for men with partners of their same age.

As this Part explores, many (including the Model Penal Code) recommend opportunities for juvenile release after ten years, which would mean people being released in their mid-twenties. California should aspire to bring its average age of release closer to this mark.

i. Meaningful vs. Geriatric Release

Recent court decisions have focused on age at the time of release in interpreting Graham; their reasoning supports the idea that mere release from prison at some age is not necessarily meaningful. Rather, as discussed in Part I, many courts have entertained the idea that parole eligibility in old age is not the kind of meaningful opportunity contemplated by Graham and is, instead, more akin to LWOP. In State v. Null, where the Iowa Supreme Court found a 52.5 year prison sentence to amount to a de facto LWOP sentence, the Court explained, “we do not regard the juvenile’s potential future release in his or her late sixties after a half century of incarceration sufficient to escape the rationales of Graham or Miller.”[166] According to the court, “geriatric release” is not meaningful.[167] Similarly, the Mississippi Supreme Court ruled that a sentencing statute requiring a life sentence with the possibility of release at the age of sixty-five amounts to LWOP and thus violates Miller.[168]

The age at which a young offender qualifies for release impacts whether he will have the opportunity to live a meaningful life. For example, Herman Wallace was released last year after serving more time in solitary confinement than any other prisoner in the United States. Wheeled out of the prison gates on a gurney, he died two days later.[169] Although he was released from prison during his lifetime, this is not what the Supreme Court had in mind when it established the meaningful opportunity to obtain release requirement.

In contrast, young people who commit serious crimes but are released in young adulthood have gone on to make valuable contributions to society. For example, Dwayne Betts served over eight years for a carjacking he committed when he was sixteen.[170] After his release from prison in his mid-twenties, he went on to graduate from college and publish two books.[171] Edwin Desamour spent more than eight years in prison for a homicide he committed at the age of sixteen; he was released in 1997 and went on to found a nonprofit dedicated to helping young people avoid “making decisions that could lead to the double tragedy of them taking someone else’s life and ending up in prison.”[172] These are the kind of opportunities the Court contemplated; age clearly impacts just how meaningful an individual’s release may be. As the Iowa Supreme Court explains, “[t]he prospect of geriatric release . . . does not provide a ‘meaningful opportunity’ to demonstrate the ‘maturity and rehabilitation’ required to obtain release and reenter society.”[173]

In Graham, the Supreme Court considered the importance of offering juvenile offenders a “chance for fulfillment outside prison walls” and a “chance for reconciliation with society.”[174] This reasoning implies that a meaningful opportunity for release would allow juveniles the opportunity to be released with enough time remaining in their lives to find fulfillment and reconciliation. Offering young offenders hope that they will be able to earn their release was also central to the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Graham.[175]

ii. State Laws

State laws range in terms of when they allow juvenile offenders to qualify for release. Most establish the possibility of release after juvenile offenders have served somewhere between ten to forty years in prison, with an average of twenty-five years.

At the low end of the spectrum, a federal court in Michigan ordered the state to create a parole process for juveniles sentenced to life without parole; under the court’s order, young offenders could qualify for parole after serving ten years.[176] This plan has not yet gone into effect because the Sixth Circuit granted a stay while the case is on appeal.[177] Hawaii recently considered legislation that would have allowed youth offenders to be resentenced after as little as ten years.[178] This is consistent with the American Law Institute’s recommendations in the Model Penal Code, which recommends that juvenile offenders be eligible for sentencing modification after they have served ten years in custody.[179] It is also consistent with international practices and human rights principles.[180] Other states at the low end of the spectrum include California, Florida, Massachusetts, and West Virginia, all of which have established parole eligibility for some youth offenders after fifteen years.[181]

In an extensive law review article addressing parole hearings for youth offenders, Sarah Russell argues for parole eligibility at the ten year mark and critiques state laws that offer the opportunity for release only after thirty or forty years in prison, arguing that these sentences “mean being incarcerated past the typical childbearing age, past the timeframe in which one could start a meaningful career, and past the age in which one could expect parents or other former caregivers to still be alive.”[182] Social scientists have found that social connections, and relationships with family and friends, are central to people’s perceptions of having meaningful lives.[183] Similarly, raising a child is connected to meaningfulness in one’s life.[184] Release at an age that forecloses or limits these possibilities would seem to fall short of qualifying as a meaningful opportunity.

At the high end of the spectrum, Colorado and Texas require juvenile lifers to serve forty years before they are eligible for parole.[185] Louisiana provides for parole hearings for juvenile offenders after they have served thirty or thirty-five years in custody.[186]

The national median an individual with a life sentence must serve prior to becoming eligible for parole is twenty-five years.[187] A twenty-five year parole eligibility date would mean that most youth offenders would be eligible for release in their early forties and is relatively consistent with the average age of release in this study. Release in one’s early forties offers more opportunities to develop meaningful lives than those statutes that only allow for parole eligibility after an individual has served forty years, rendering them eligible for parole in their late fifties.

Youth offenders in California articulate common desires for their release: to reunite with their parents before they die and help care for them as the age; to establish families of their own; to embark on meaningful careers; and to make a positive difference in people’s lives, particularly young people who seem headed down a path to crime.[188] While S.B. 260 offers some possibilities for establishing meaningful lives after release, people would undoubtedly have greater access to creating meaning in their lives if they were paroled in their twenties or early thirties. Lowering the average age of release would ensure that California’s YOPHs provide more meaningful opportunities, as contemplated by Graham.

B. Likelihood of Obtaining Release

Graham and Miller will not result in meaningful changes to the law if parole is merely an illusory possibility.[189] As the Supreme Court implied in Graham, a realistic chance of being released is also necessary to render the opportunity meaningful.[190] While S.B. 260 made release more realistic for youth offenders during its first six months, release was still unlikely. As discussed in Part II, thirty-five out of 109 people were ultimately released under S.B. 260 during the study’s timeframe, at a rate of only thirty-two percent (when factoring in reversals by the Governor).

The mere existence of a parole hearing does little to distinguish an LWOP sentence from a life sentence if the possibility of being released is slim, as it often is. Sharon Dolovich argues there is “little practical difference” between LWOP and life with the possibility of parole sentences.[191] According to Dolovich, whereas parole hearings in the mid-twentieth century were a “meaningful process in which parole boards seriously considered individual claims of rehabilitation,” they have developed into “in most cases a meaningless ritual in which the form is preserved but parole is rarely granted.”[192]

Nationwide, only a fraction of those who are eligible for parole are actually released. In New York, the parole release rate is thirteen percent for people serving life sentences for violent felonies.[193] Michigan’s release rate for lifers was 8.2% over the past thirty years.[194] Ohio’s dipped to 6.9% in 2011.[195]

In 2010, a California inmate serving a life sentence in California had an eighteen percent chance of being granted parole by the parole board and a six percent chance of actually being released.[196] Things have changed since 2010, in large part because California’s current governor allows a much higher number of BPH decisions to stand.[197] In 2014, life prisoners had a thirty-two percent chance of being found suitable for parole and a twenty-six percent chance of being released.[198]

S.B. 260 significantly improved the likelihood of release for juvenile offenders in the first year of its implementation. In 2014, YOPHs were more likely than parole hearings involving adult offenders to result in findings of suitability.[199] In the first eleven months of 2014, forty-three percent of YOPHs resulted in findings of suitability in contrast to thirty-two percent of non-YOPHs; the grant rate for YOPHs was eleven percent higher than for other parole hearings.

These findings indicate that California’s law may be accomplishing what it set out to do. However, S.B. 260’s opportunities do not seem realistic enough. The majority of YOPHs in the first year resulted in denials. The law may not be having the transformative effect many contemplated it would. In Part IV, I discuss several changes that have the potential to make the likelihood of release more realistic.

C. Access to Rehabilitative Programming

An offender must generally demonstrate that he or she has been rehabilitated in order to be found suitable for parole. Offering opportunities for young offenders to rehabilitate while they are in prison is fundamental to providing a meaningful opportunity for release. If they do not have access to rehabilitative programs, it will be nearly impossible to prove they have been rehabilitated in their parole hearings.[200] The transcript review portion of the study confirmed that limited access to rehabilitative programming is a major obstacle facing youth offenders seeking parole under S.B. 260. Greater access to rehabilitation is a critical requirement for ensuring meaningful opportunities for release.

Across the country, juvenile offenders serving life sentences are often prohibited from participating in rehabilitative programming while in prison.[201] One national survey found that sixty-two percent of juvenile lifers were not participating in rehabilitative programs in prison despite the fact that most desired to do so.[202] Eighty-two percent of those not enrolled in programs indicated that they wanted to participate but could not because either the prison did not offer such programming or they had been denied the opportunity to participate.[203]