Searching for Optimal Governance on the Nonprofit Board: Dynamic Resource Constraints and a Rejection of Board Bifurcation

Introduction

Jonah Peppiatt∞

I. Introduction

II. The Problem: Contract Failure, Nonprofit Board Duties, and Enforcement

A. Background: The Role of the Nonprofit Corporations

B. The Nonprofit Board’s Legal Duties: Loyalty, Care, and Obedience

C. Filling the Void: Best Practices

III. Case Study Findings: Governance Failures at a High Performing Organization

4. Summary of ALSONY’s Board Practices

C. Individual Participation in Governance

4. Summary of Individual Participation in Governance

IV. A (Somewhat) New Theory of Nonprofit Governance

A. Flaws in the Conventional View

B. Director Resource Constraints and the Theory of Optimal Governance

C. The Bifurcation Solution and Its Flaws

V. Recommendations and a Final Thought

A. Incorporating a Resource-Constrained View of Governance to Best Practices

I. Introduction

In the summer of 2013, bribery scandals rocked the New York City nonprofit world. At the “92nd Street Y” cultural center on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, Executive Director Sol Adler was fired amid accusations of a sexual relationship with a subordinate.[1] Allegations also emerged that the son-in-law of this same subordinate, also a 92nd Street Y employee, was connected to multiple New York crime families and had been demanding side payments from vendors.[2] At the Metropolitan Council on Jewish Poverty (“Met Council”), another New York City nonprofit, Executive Director William Rapfogel was arrested for stealing over five million dollars from Met Council in a kickback scheme with city developers.[3] As members of the New York City nonprofit community attempted to understand what happened at two of New York’s largest and best-known nonprofit organizations, attention naturally turned to these organizations’ boards of directors. But as the President and Chief Executive Officer (“CEO”) of the Jewish Funders Network noted in reacting to these scandals, “[n]obody in those boards had bad will . . . they simply didn’t have the mechanisms in place [for] more effective governance.”[4]

In both the nonprofit and for-profit contexts, one of the key roles of the board of directors is to provide oversight of the managers, such as the CEO and other high-level executives, who run the organization’s day-to-day operations. As part of their fiduciary duties to the organization, directors must oversee, among other things, executives’ operational and financial decision-making, pay, strategic planning, and (in the nonprofit context) adherence to the organization’s stated mission, to ensure that their broad powers are used properly. This oversight work is called “governance.”

In both the nonprofit and for-profit contexts, governance plays a crucial role in the long-term functioning of an organization. Where boards of directors fail to govern, executives may become lazy, reckless, or overly greedy, to the detriment of the corporation or organization. In the for-profit context, this results in lower or negative profits. In nonprofits, where success is measured (to the extent it is measured at all), by the nebulous concept of “mission fulfillment,” a lack of governance may simply result in operations that do not further the organization’s mission or, in more dire cases, in management looting corporate resources.[5] Governance is, by and large, the collective effort of a board of directors to prevent a corporation from being run poorly or for personal, rather than corporate or public, benefit.

In recent years, many organizations and government agencies have worked to bolster governance among nonprofit boards of directors. These entities have posited various iterations of “best practices”—procedures that, if followed, should lead to better governance. The conventional wisdom is that strict adherence to best practices leads to better governance and, in the nonprofit context, more effective mission fulfillment. This article argues that, where nonprofit and director resources are constrained (and they nearly always are), more director participation in governance and adherence to best practices may actually detract from mission fulfillment by causing a misallocation of resources. Instead, this article argues that any such “best practices” aimed at increasing governance in nonprofits need to be examined in light of individual and collective board resource constraints, and should only be adopted where director and board resources cannot fulfill some other, more useful (or mission-fulfilling) purpose.

Part II of this article examines the duties of nonprofit directors and describes the problems that nonprofit organizations face in enforcing the duty of boards of directors to govern. Part II also explains the current framework of nonprofit “best practices” that attempts to solve these problems.

Part III describes a case study of a New York-based nonprofit organization that has adopted what I call the “conventional” approach to nonprofit best practices, and highlights at least two problems with this approach.

Part IV presents a robust framework—a Theory of Optimal Governance—for thinking about the relationship between director participation in governance, mission fulfillment, and individual director resources, in an attempt to answer two crucial questions:

(1) Why do nonprofit directors in organizations with governance “best practices” in place still not govern, or govern less than they supposedly should?

(2) If such organizations still appear to be fulfilling their mission, is there a need to fix the underlying governance problem?

The Theory of Optimal Governance rests on two key principles supported by the results of the case study. The first is that, because best practices are not tailored specifically to the governance functions of the board, any increase in adherence to best practices will result in only a diminished increase in governance. In other words, increasing best practices does not lead to a one-for-one or dollar-for-dollar increase in director participation in governance activities, such as oversight of the executive director. For example, if one best practice is that board members attend five board meetings per year, and the current norm of meeting attendance for the organization is four meetings per year, an increase to five meetings could have absolutely no impact on the board’s overall involvement in governance in the form of oversight. The board could still spend the same amount of time annually on governance, only split between five meetings instead of four. Or, certain board members could still attend only four meetings if the board has no sanctioning mechanism in place to enforce the best practice. Ultimately, in many cases, collective and individual board member resource constraints will play a much greater role in determining the amount of governance the board engages in than will institution of any particular best practice.

The second principle of the Theory of Optimal Governance is that governance and mission fulfillment, though related, are separate functions of the board, and accordingly, an increase in governance may or may not increase mission fulfillment. Given the resource constraints of directors, there is an optimal level or amount of governance somewhere below maximum governance. If the board of directors strives to govern at this level, it will provide sufficient governance for the organization to survive and grow while allowing the board of directors to help the organization in other ways. The optimal level of governance is the level that provides the best trade-off for the organization between governance and mission fulfillment.

Jonathan Small and Michael Klausner have implicitly accepted this framework in their article, Failing to Govern, in which they advocate that nonprofit boards adopt a new structure that they term “bifurcation” under which nonprofit boards of directors are divided into a “governing” and “non-governing” board. This article explains why resource constraints make bifurcation an unsatisfactory answer to the questions posed above.

Notably, both the Theory of Optimal Governance and the solutions put forth by Klausner and Small reject the conventional wisdom of governance—the idea that the implementation of best practices improves governance, which in turn increases mission fulfillment. This conventional wisdom is flawed for two reasons: first, the best practices so often put forth by organizations focused on improving nonprofit governance address, and are meant to address, organizational issues both within and beyond the scope of governance-specific failures; and second, because governing and ensuring mission fulfillment are distinct functions of nonprofit boards, an increase in governance due to the implementation of best practices may increase mission fulfillment in some instances, but reduce it in others.

The Theory of Optimal Governance states that there is an optimal level of governance that ensures sufficient governance while permitting directors to fulfill the myriad other responsibilities of directorship that further the organization’s fulfillment of its mission (i.e., providing the organization with “wealth, wisdom, and work”). The theory rests on the premise that because directors’ participation in both governance and mission fulfillment is in tension due to directors’ individual resource constraints, the optimal level of governance is always below the maximum amount of governance that may be possible.

Finally, Part V offers recommendations to help nonprofit boards improve governance and allocate resources. These recommendations include increasing transparency around individual directors’ participation in governance, providing clear communications as to which director responsibilities are related to governance and which are not, and building board members’ governance activities directly into the board’s collective schedule so that board members are not left to perform governance tasks on their own time.

II. The Problem: Contract Failure, Nonprofit Board Duties, and Enforcement

In fulfilling their fiduciary duties, nonprofit directors have simultaneous imperatives that often conflict, including management oversight and mission fulfillment. Due to legal and practical limitations on the enforcement of those duties, many have presented “best practices” for boards of directors to serve as a duty enforcement substitute.

Part II(A) briefly describes two theories of nonprofit existence that provide complementary explanations of how nonprofit boards have become the guardians of both governance and mission fulfillment. Part II(B) then discusses in detail the board members’ fiduciary duties under existing law and how various legal and practical considerations limit their enforcement. Finally, Part II(C) explains the role of “best practices” as the proverbial carrot to the broken stick for ensuring directors’ fulfillment of their governance obligations.

A. Background: The Role of the Nonprofit Corporations

The generally recognized objective of a for-profit company is clear and measurable—the maximization of shareholder wealth.[6] To this end, the function of the board of directors is to monitor management’s pursuit of this goal and hold the company’s executives accountable for failures.[7] Shareholders can, theoretically, vote out directors who do not tame renegade managers.[8]

In contrast, the nonprofit corporation does not have shareholders to whom profits inure; indeed, the primary distinction between for-profit and nonprofit corporations is that nonprofits are subject to what is known as the “non-distribution constraint,” which requires any profits generated by the corporation to be reinvested in its enterprise rather than distributed to shareholders or other parties with an interest in the corporation.[9] Subject to the non-distribution constraint, nonprofits may generally be formed for any lawful purpose; the purpose for which the nonprofit is created forms the basis of the “mission” it must fulfill.[10]

Theories abound as to the purpose of the nonprofit entity. Henry Hansmann argues that the role of the nonprofit in society is to solve problems of contract failure;[11] those who wish to give to charity (which, in his view, amounts to the purchase of services for another) often cannot get the feedback necessary from the charitable beneficiaries to make market-driven decisions about where to invest. As a result of this “contract failure,” according to Hansmann, a for-profit firm operating in the charity market would have an incentive to short-change beneficiaries (for example, by cutting the quality of services) to increase profit margins.[12] The non-distribution constraint solves this problem.[13]

The contract failure theory of nonprofits needs supplementation, however. Clients of legal services organizations that assist nonprofits, for example, pay a reduced fee amount for services. As clients are thus both the purchasers and the beneficiaries of the services, the nonprofit’s beneficiaries can provide effective feedback to its donors, and the organization’s existence is thus not fully explained by the contract failure theory.

Mordecai Lee presents an alternative explanation for the existence of nonprofits, derived from the Supreme Court’s 1819 holding in Dartmouth College v. Woodward that nonprofits are private corporations.[14] The Court held that a nonprofit (Dartmouth College) was a fundamentally private enterprise even though it was founded with a public purpose (education), and that as a result, the government could not intervene in Dartmouth’s affairs.[15] Lee argues that this private character of nonprofits, rather than some unitary purpose in ordered society (i.e., contract failure), defines nonprofits largely as a multi-purpose tool for the private sector.[16] In other words, a nonprofit can be whatever its founders want it to be as long as it does not violate the non-distribution constraint.[17]

Lee’s argument implies that nonprofits, whether charitable or merely private, exist to serve the goals of their founders and supporters. This instrumentalist view of nonprofits presents a plethora of possible explanations for their existence that can either supplement or supplant the contract failure theory. Take again the example of a legal services organization that assists nonprofits; assume that large law firms support it, as they do many legal services nonprofits. Such a nonprofit may exist simultaneously to serve as a training ground for inexperienced law firm associates or allow the law firm sponsors to provide similar services to different clients at drastically different rates (i.e., price discrimination).

Whether a nonprofit exists to address a contract failure or as a purely private instrumentality, a nonprofit corporation must have some stated purpose. The role of a board of directors is to ensure the fulfillment of that purpose by overseeing management. This oversight work is called governance.

B. The Nonprofit Board’s Legal Duties: Loyalty, Care, and Obedience

To govern, the nonprofit board of directors must monitor the organization’s chief executive and ensure that the organization’s strategic and financial planning furthers its mission.[18] In this effort, the nonprofit board faces many obstacles familiar in the for-profit context: agency costs of dispersed management, monitoring limitations, board member shirking, and potential director liability for actions taken by the firm, to name a few.[19] Further complicating matters are the nonprofit board’s dual objectives. While the for-profit corporation has a clear, measurable end—profit maximization—the nonprofit’s goal—mission fulfillment—is difficult to define or measure.[20] In the absence of an actively governing board, the CEO and other executives have free reign to dominate the nonprofit and direct pursuit of its mission. In the most benign cases, a good CEO will be an able and unfettered steward of the organization’s resources, and perhaps do significant good in the most efficient way possible. But in other cases, a board’s deference can result in the kinds of scandals visited upon the 92nd Street Y and Met Council in 2013.

The law attempts to ensure both a nonprofit board’s effective governance and its pursuit of mission fulfillment through the imposition of three fiduciary duties: the duty of loyalty, the duty of care, and the duty of obedience. The duty of loyalty requires the fiduciary (i.e., the board of directors) not to act adversely to the organization.[21] Although the duty of loyalty helps protect against corporate self-dealing and other acts committed in bad faith, it only ensures a bare minimum of good conduct.[22] It is easy to imagine a board that refrains from self-dealing without governing well. Legal mechanisms for punishing the worst actors exist, but are largely beyond the scope of this article.[23] The duties of care and obedience, on the other hand, require the board to, respectively, govern and ensure that the organization pursues its mission. Effective means of legally enforcing either of these duties, however, do not exist.

The board’s oversight function and responsibility for business decisions emanate from the duty of care; it is the crux of good governance. In Failure to Govern, Michael Klausner and Jonathan Small responded to a spate of nonprofit scandals similar to those consuming the New York City nonprofit community in 2013, finding that “many directors are not governing” (i.e., directors at the organizations in question were not fulfilling their duty to oversee management—their duty of care).[24]

When directors do not govern, the executive director is allowed to dominate the organization. An oft-noted feature of nonprofit boards is deference to management, particularly when it comes to “deciding what the board should decide.”[25] Many boards “defer[] excessively to the chief executive.”[26] In the for-profit corporation, excess deference rising to the level of gross negligence constitutes abdication of the duty of care—a standard that applies equally to nonprofit organizations.[27] In nonprofits, where resources are limited and board members often have less expertise, a high (though not “excessive”) level of deference is considered by some to be “desirable” because, in many cases, directors are not experts in the nonprofit world, and a lack of deference can be characterized as meddling.[28] A recent study also showed that while there is no correlation between measures of executive strength and board member attendance or participation in governance activities, strong executives are associated with high levels of board member giving.[29] However, board independence is still considered an essential check on executive power.

Without an independent board, a nonprofit organization becomes vulnerable to mismanagement or outright malfeasance,[30] resulting in the types of scandals that afflicted the 92nd Street Y and Met Council in 2013. Indeed, one prominent funder, responding to those scandals, noted that long-time executives such as Sol Adler and William Rapfogel often preside over organizations where the board “does not feel like they need to, or can be, [an effective] power check on the executive.”[31] Taken to its logical conclusion, this understanding implies measureable effects of director non-governance. In the most benign cases, this might simply mean the reinforcement of an executive director-dominated culture and perpetual “vulnerability.”[32] In serious cases, however, governance failures will lead to scandals and pecuniary losses for organizations that will make it difficult to fundraise or even continue the organization’s existence; in the case of Met Council, for example, New York City suspended millions in government funding for the organization.[33]

Oversight of a board’s fulfillment of its governance duties is squeezed at both ends. According to one recent article, the unwillingness or inability of many boards to speak truth to executive power is a function of four main constraints: “lack of time . . . information . . . familiarity with the ‘business’ [of nonprofits, and] a desire to avoid tension and conflict.”[34] Part V addresses these “resource constraints” in greater detail. While board members’ independence is constrained by their limited resources, any outside enforcement of board members’ duty to govern is cabined by the absence of legal means for a nonprofit stakeholder to sue or otherwise enforce a duty of care violation.

Under New York’s nonprofits law,[35] the fiduciary duty of care of nonprofit directors mirrors the duty of care of for-profit boards of directors (known as the “business judgment rule”); however, while for-profit directors operate under the prospect of being voted out by shareholders, nonprofit directors have no backstop enforcement mechanism. Several commentators have questioned whether the business judgment rule is an appropriate fit for nonprofits.[36] However, nonprofit law does not apply distinguishable standards of the duty of care to nonprofit boards.[37] Indeed, the New York Not-For-Profit Corporation Law (“N-PCL”) sections that describe these duties are lifted almost verbatim from the state’s Business Corporations Act.[38] These include section 701, which designates the board’s authority (“a corporation shall be managed by its board of directors”)[39] and section 717, which provides the duty of care (directors will be held to the standard of care of “an ordinarily prudent person in a like position”).[40] The latter has been interpreted to imply the “business judgment rule” standard, which means that so long as a board uses a reasonable decision-making process, the substance of its decisions are not subject to court review.[41] This is an extremely deferential standard that protects directors for any decision taken absent a showing of gross negligence or recklessness.[42]

The insulation of nonprofit directors from duty of care liability for governance failures goes beyond the protections of the business judgment rule. Many nonprofits provide indemnification clauses in their bylaws that ensure directors cannot be held liable for acts that do not rise to the level of bad faith (i.e., directors can only be held liable for actions that might fall under gross negligence or recklessness in the duty of care context).[43]

Even in the absence of indemnification clauses, nonprofit stakeholders rarely have the ability to sue.[44] The closest equivalent to a stockholder in the nonprofit corporation context is the donor. In most cases, however, only the state attorney general (and not the charitable donor) has standing to sue a nonprofit for a breach of fiduciary duty.[45] Should the attorney general fail to act, courts will only grant standing to a private party in the face of “improper attorney general behavior or . . . disabling conflicts of interest.”[46] This poses a genuine obstacle, as attorneys general rarely pursue duty of care claims because they have more pressing cases to deal with and face administrative logjam; they believe we should “let charitable directors direct”; and duty of care cases are notoriously difficult to win under the business judgment rule.[47]

The duty of obedience is unique to the nonprofit context and requires directors of the board to ensure a nonprofit operates for its stated charitable purpose. Several authors have argued in favor of making the obedience doctrine a more robust, if aspirational, means of enforcing director efficacy.[48] However, an attempt to shoehorn mission fulfillment into the realm of enforceable legal duties would more likely flounder in the face of the “ephemeral and virtually nonjusticiable” nature of nonprofit missions.[49] Furthermore, the standing requirement that prevents charitable beneficiaries and donors from bringing claims against a nonprofit board would be just as much a problem in enforcing the duty of obedience as it is to the enforcement of the duties of care and loyalty.[50]

C. Filling the Void: Best Practices

In response to the ineffectiveness of the legal system in enforcing either nonprofit board governance or adherence to the organization’s mission, practitioners in the nonprofit community have developed a cadre of “best practices” that are generally accepted as beneficial and meant to improve nonprofit governance.[51] The American Law Institute (“ALI”), the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”), and the New York Attorney General’s Office, along with several other practitioner-focused organizations such as Governance Matters and BoardSource, have highlighted several best practices that, although not legally enforceable, can serve as a baseline upon which to build good governance.[52] These functions include adopting bylaws, holding meetings, setting organizational policies, providing oversight of executive officers and finances, and “monitoring implementation of the charity’s purposes.”[53] Best practices involve more specified permutations of these options, such as holding a minimum number of board meetings per year, having restrictions like term limits on membership, or requiring all board members to participate in a board committee.[54]

Best practices are not legally enforceable. A board draws its functions and practices not from the law,[55] but from organizational rules (i.e., corporate bylaws), informal suggestions of board members and staff, and adopted practices. There are only limited proverbial “sticks” to enforce director compliance with best practices. And because directors serve on a voluntary basis and receive no remuneration, attempts at enforcement carry organizational risks. Admonishment by a staff member or the threat of removal may only serve to disincentivize board membership and director participation, and may also cause problems in the politics of fundraising if directors are significant donors.

In addition, the implementation of best practices only indirectly addresses the governance problem; such practices rarely recognize the distinction between “governance” responsibilities and other functions, and the competing imperatives that board members face.[56] Generally, nonprofit corporations expect directors to provide the “Three W’s” in their service to the board: wealth, wisdom, and work.[57] None of these categories, however, explicitly relates to governance. A board member can provide wealth, wisdom, and work while not governing at all. For practices to induce governance, they must cause board members to both provide the Three W’s and govern.

At best, some board practices combine expectations of non-governance actions at the individual level with limited governance functions. For example, high-functioning boards often have the nonprofit issue each board member an evaluation detailing their performance over a year of service.[58] One report card reviewed for this article had five elements: three related to fundraising or donations, one to meeting attendance, and one to sitting on a committee.[59] Only one of these measures—meeting attendance—directly relates to satisfying the board member’s duty to govern; if a director does not attend meetings, she cannot perform crucial governance functions, such as discussing the executive director’s performance and pay. As noted in Part I, however, even a meeting attendance requirement may not result in any increase in governance on its own. That none of the Three W’s satisfies the board’s governance duty while all three may satisfy its duty of obedience to the mission further shows the potential disconnect between what is asked of board members and their first-order governance responsibilities. The problem is also terminological. Many organizations that formulate and articulate such practices refer to the comprehensive suite as “governance practices,” rather than distinguishing between governance practices and practices directed at other nonprofit goals, such as fundraising or mission fulfillment.

The consensus among practitioner organizations is clear: increased adherence to best practices improves both governance and mission fulfillment. The Nonprofit Coordinating Committee of New York (“NPCCNY”), which presents annual awards to organizations exhibiting excellence in such practices, believes that promoting good governance strengthens all nonprofits.[60] NPCCNY, an organization that advises nonprofit boards on best practices, notes that well-governed boards “ensure that the organization’s mission is clear, appropriate and relevant.”[61] This view implies that an increase in the enforcement of best practices will increase governance, and that increased governance will increase mission fulfillment.

But what if this is not the case? What if nonprofit directors in organizations with good practices in place still do not govern? And what if organizations with governance problems still appear to be fulfilling their mission? The case study below examines one legal services nonprofit in New York City, and finds just such a situation.

III. Case Study Findings: Governance Failures at a High Performing Organization

This Part describes the findings of a case study of an anonymous legal services organization in New York (hereinafter “ALSONY”).[62] ALSONY was given anonymity in exchange for providing full access to its officers and directors and confidential organizational documents. All identifying characteristics of ALSONY have been removed from this article. The case study shows that there are, indeed, organizations faced with the conundrum of well-implemented best practices but significant room for improvement in terms of actual board member participation in governance activities. Further, the case study shows such an organization that appears to be effectively fulfilling its mission. In other words, ALSONY serves as an ideal example for asking whether the organization needs more, or better, governance. As discussed in Part IV, the answer may be, surprisingly, “no.”

The case study begins in Part III(A) with a brief introduction to ALSONY[63] and its board of directors, and proceeds with an examination of the board’s implementation of best practices and the behavior of individual board members. In detailing the board’s best practices, Part III(B) compares the board’s practices to widely accepted examples of best practices in the nonprofit sector. Part III(C) then describes board member behavior by analyzing data from two sources: a survey of board members, and “report cards” issued annually by ALSONY (and prepared by the nonprofit’s senior staff) that detail individual board members’ duty fulfillment. Part III(C) compares this data to an index of sector-wide director behavior. Part III(D) examines mission fulfillment indicators in an attempt to judge ALSONY’s performance in mission fulfillment. Part III(E) concludes the case study.

This article seeks to answer why nonprofit directors do not govern maximally when best practices are in place, and whether organizations need to address this problem when they are performing well in terms of mission fulfillment. This case study presents, as an example, an organization that appears to have many recognized best practices in place, but whose board members could govern significantly more than they currently do. At the same time, ALSONY appears to be pursuing and fulfilling its mission effectively.

ALSONY is a nonprofit that provides legal services to clients who cannot afford representation at market prices. As part of its model, ALSONY’s volunteer base includes law firm attorneys. It is funded by a combination of law firm and individual donations as well as public and private grants.

ALSONY’s board is primarily comprised of private sector lawyers.[64] Under its bylaws, board membership is limited to no fewer than three and no more than thirty members,[65] and board size has remained fairly constant over the past few years (ranging between seventeen and twenty-two members).[66] The composition of the board suggests that board members would have good knowledge of their duty to govern. As practicing (and accomplished) attorneys, they should either understand the nature of basic fiduciary duties associated with directorship, or know to ask questions as to their responsibilities under the law. Governance responsibilities, unenforceable though they may be, are ultimately legal responsibilities.

In other words, a board of lawyers might be considered a “model” board for examining director participation in governance. One would expect such a board, with appropriate best practices in place, to display close to maximum governance behavior. If there is a discernable lack of governance here, it cannot be attributed to directors not fully understanding their duties; some other factor or factors must be limiting directors’ participation in governance.

BoardSource, Governance Matters, NPCCNY, and the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) each detail a variety of best practices for nonprofits. Though each organization articulates a slightly different suite of best practices, there is substantial overlap.[67] Many of these practices fall into one of three categories: board procedure, committee work, and board engagement. This case study compares ALSONY’s compliance with a sampling of four variations of generally recognized practices within each of these three areas.[68] Though different sources describe the practices in slightly different terms, this case study favors more specific criteria in comparing ALSONY’s board to the industry standard, for the sake of evaluation.

Four best practices fall within the “board procedure” category: receipt of a written job description and review of the certificate of incorporation and bylaws by directors prior to joining, an annually set meeting schedule with at least three meetings,[69] meeting materials (including an agenda, detailed minutes, and materials to be discussed) provided in advance of each meeting,[70] and a formal board member selection process.[71]

ALSONY provides board members with relevant documentation prior to joining the board, sends out meeting materials one week prior to the meeting, and convenes the board five times each fiscal year. The board selection process, however, deserves further discussion. According to Governance Matters, a board selection process should include a formal nomination and interviewing process.[72] To maintain its volunteer and funding base, however, ALSONY relies on relationships with law firms and thus reserves many directorships for a particular law firm.[73] Such a firm then nominates a board member (though that board member may have been requested by ALSONY staff).[74] While extraordinary for most nonprofits, the legal services industry commonly uses this model and does not view it as a problematic practice. On the whole, it appears that ALSONY has adopted appropriate practices when it comes to board procedure, although the board member selection process is somewhat unconventional when compared to other nonprofits.

Four best practices characterize “committee work”: each board member should serve on at least one committee, with committee chair term limits to prevent stagnation; the standing committees should include, at minimum, a governance committee, a finance committee, an audit committee, and an executive committee; committee responsibilities should be written and tasks assigned; and a staff member should work with each committee to assist in providing accurate and useful information.[75]

ALSONY’s compliance with these practices, according to board documentation, appears to be complete. The board has seven standing committees in total,[76] including the Executive Committee; the Finance Committee; the Audit Committee; and the Board Resource and Governance Committee, which nominates candidates for directorship.[77] The bylaws describe the responsibilities for each committee.[78] The committees do not have charters beyond short descriptions included in the bylaws, but the organization holds each committee chair responsible for assigning tasks and ensuring their completion.[79] Finally, ALSONY assigns staff to liaise with each committee.[80]

As with the board procedure practices, ALSONY has adopted practices for its committees that comport with accepted best practice standards. Nonetheless, its committee work practices might benefit from further memorialization; the lack of charters for committees is not ideal, and no organizational document formally describes the role of the committee chairs in assigning tasks; and the absence of written responsibilities for committees and their leaders may lead to confusion and disagreement as to these roles and responsibilities.

Four best practices for “board engagement” include: the board understands its legal obligations; the board is engaged in financial oversight (including review of financial statements and budgets) and executive evaluation (including setting compensation); the board evaluates individual goals for fundraising, committee work, and volunteering annually; and board members all give annually and participate in fundraising.[81]

The composition of the ALSONY board strongly suggests that its members understand their legal obligations (as all are attorneys). The board member “report cards” issued annually by ALSONY address fundraising and committee participation but not volunteerism.[82] One hundred percent of board members give annually to ALSONY. The Board Member Responsibilities document provided to directors when they join ALSONY’s board includes oversight of the annual audit, periodic financial reports, and the budget, and the monitoring of executive performance and pay.[83] The board delegates a good portion of this work to the Executive and Finance Committee, which reports findings both orally and in writing to the board as a whole.[84] As long as the committees report to the board as a whole and the board has final decision-making authority on these issues, this practice is perfectly acceptable and not at all out-of-the-ordinary for a nonprofit board. ALSONY’s executive director states that the board does indeed follow these standard protocols.[85]

4. Summary of ALSONY’s Board Practices

On the whole, ALSONY appears to have near-perfect deployment of board practices in each of the three areas discussed; the practices they have in place align with widely advocated recommendations put forth by various practitioner-focused organizations.[86] Though this case study only examined a sampling of total practices, the sample appropriately represents quantifiable structures advocated by organizations such as BoardSource and Governance Matters. The discussion above thus justifies the following assumption: ALSONY has a near-maximum level of best practices in place. In light of that assumption, Part III(C) examines individual board members’ participation in governance to understand whether and how deployment of best practices might impact such participation.

C. Individual Participation in Governance

Under the conventional view of optimal nonprofit governance, individual board members should display maximum participation in governance to fulfill their fiduciary duties, and that implementation of recognized best practices will facilitate such participation. This Part assesses governance participation by ALSONY’s directors in four areas. The data used comes from a forty-question survey of board members and the annually issued board member report cards, and examines the behavior of ALSONY’s directors.[87] Most survey questions address board member participation in governance in the areas of board independence, executive oversight, and financial oversight, three areas with large implications for fulfillment of the duty of care; all three are directly related to the executive director’s power.[88] The report cards largely focus on measuring board member activity through attendance and fundraising data.

In an attempt to assess the power of ALSONY’s executive director, board members were asked a series of questions about the Executive Director’s role in a variety of board protocols. Board members acknowledged the strong hand of ALSONY’s executive, with nearly all board members noting that the Executive Director is involved in setting the meeting agenda.[89] Additionally, forty-five percent of respondents indicated their belief that the Executive Director nominates new board members, a proxy for executive strength used in previous studies. A majority of board members also noted that they would speak privately to the Executive Director if the board were going to make a decision with which they disagreed; only a third said they would speak privately to other board members who they believed would support their position. In addition to these various proxies for executive strength, board members were also asked to characterize the strength of ALSONY’s executive vis-à-vis the board on a scale of one to five, with one being the strongest. Sixty percent of directors gave the executive a rating of one, and just under seventy-five percent gave either a rating of one or two. Board members were also asked to rate the board’s independence from the executive director on the same scale, and roughly eighty percent answered with a rating of one or two.

Clearly, ALSONY has a strong executive, which may be indicative of excess deference on the part of board members. While the directors appear to view themselves as independent in the face of executive power, the directors’ other responses call that conclusion into question. Board members, for example, go directly to the Executive Director with concerns rather than talking to one another first, which could have a chilling effect on independent, collective board action. Furthermore, despite the bylaws’ call for nominations to be made by a committee,[90] the prevalent belief that the Executive Director makes nominations indicates the executive’s central role in shaping not only the agenda, but also the composition of the board.

To fulfill its oversight function, the board must, at minimum, evaluate the performance of ALSONY’s chief executive and set his or her salary.[91] According to the BoardSource Nonprofit Governance Index, which measures performance sector-wide, this is usually an area in which nonprofit boards perform at least adequately, with over seventy percent of boards receiving a written report on executive performance, reviewing data on comparable compensation, and voting on the executive director’s pay.[92] At ALSONY, the board delegates primary responsibility for reviewing executive performance to the Executive Committee (consisting of the board Chair, Vice Chair, Treasurer and Secretary), which then reports to the board.[93] Still, responsibility for executive review rests with the board as a whole, and is expressly listed in the Board Member Responsibilities document.[94]

ALSONY’s Form 990,[95] the publicly available reporting form that all nonprofits must file with the IRS, indicates that the executive committee uses data from other organizations to help determine the appropriate level of executive compensation.[96] This complies with the industry practice of using comparative compensation data.[97] However, polling among the individual board members reveals a lack of engagement with executive oversight and compensation. Directors were asked to identify the role they played in evaluating the Executive Director’s performance. Over forty-five percent said they played no role in evaluating performance whatsoever, and over thirty-five percent did not receive a report from the Executive Committee. Of those that did play a role in the evaluation, ninety percent only heard an oral report from the Executive Committee and received nothing in writing. Only ten percent of those responding received both written and oral reports.[98]

On executive compensation, the survey responses again indicate less-than-expected individual engagement. This is problematic because, as noted above, one of the board’s primary roles is to oversee the executive director, and setting the executive director’s compensation forms a key component of such oversight. Because nonprofits, like any other business, operate in a competitive market for CEO talent, it is important for directors to not only monitor the executive director’s stewardship of the organization, but how that stewardship measures up to that of CEOs of similar organizations and how compensation compares to market standards.

ALSONY’s directors were asked whether they knew the executive director’s compensation and, if so, how much it was. Forty-five percent openly stated that they did not know the executive director’s compensation for the most recent fiscal year. Of those claiming that they did, only twenty-seven percent came within $10,000 of the correct amount when asked how much it was.[99] Asked about their involvement in determining that amount, some directors said they had heard a report on the amount, voted on it, or helped determine it (though in some cases, apparently, without knowing the final amount), but none reported that they had asked questions about it. This lack of familiarity with the details of executive compensation may be another indicator of the board’s excess deference to the CEO, even on matters of pay.

Board members indicated a greater level of involvement in financial oversight of ALSONY; board participation in this area can be crucial to ensuring that scandals like those that rocked the 92nd Street Y and Met Council in 2013 do not occur. One hundred percent of board members responding to the survey indicated having received and read the operating budget for the latest year. Ninety-two percent read the auditor’s report and accompanying financial statements. Directors were less consistent in having received and read a copy of ALSONY’s Form 990 (fifty-five percent), perhaps because that document is not formatted for easy reading. On the whole, this can be considered a high level of governance activity. Notably, industry-wide engagement in financial oversight, according to the Nonprofit Governance Index, is also high.[100]

4. Summary of Individual Participation in Governance

Overall, in areas of both board independence and executive oversight, members of ALSONY’s board exhibit less than maximum participation in governance. The organization’s executive director wields significant power, with the ability to shape the board’s composition and agenda, and to cut off objections to policy before they reach the whole board for debate. This does not mean the executive director actually uses these powers to stifle governance, but that the board is vulnerable to such use. Additionally, only a select few members of the board appear to be actively involved in evaluating the executive or setting her pay—the two functions that may most directly implicate a board’s duty of care. On a positive note, ALSONY board members’ engagement with financial oversight appears to be in-line with principles of effective governance.

How does board member participation in governance impact an organization’s ability to fulfill its mission? Based on the conventional wisdom about governance (as detailed below) one might expect that a board with such governance gaps would struggle to fulfill the organization’s mission. Part III(D) attempts to evaluate ALSONY’s ability to fulfill its mission.

Measuring the success of the enterprise in fulfilling its mission is, perhaps, one of the most difficult tasks nonprofit organizations face. It is particularly difficult for ALSONY, because the direct impact of its work cannot be seen on the ground. Although it aims to improve the lives of low-income New Yorkers, ALSONY can only infer outcomes for these groups from the success of the nonprofits it works with. In recent years, ALSONY has begun surveying its volunteers and clients, as well as paying closer attention to the volume of both of these groups, in an attempt to derive a statistical measure of year-to-year success.[101] It would be overly ambitious for this case study to attempt to determine what might be the “best” way to measure mission success. However, given a set of board-accepted metrics, Part III(D) attempts to identify what role the board plays in mission fulfillment—its prescribed duty.

In the survey, board members were asked to rank what they consider to be the best indicators of the success of the organization as a whole, the executive director, and the board in fulfilling ALSONY’s mission. Roughly two-thirds of board members believe that positive client satisfaction surveys are the best indicator of organizational mission fulfillment. These indicators are also widely viewed as the best markers of success for the Executive Director. The board could not reach a clear consensus on the best indicator for their own success.

A look at ALSONY’s client survey shows an astonishingly high success rate by this measure; in FY2010, the client satisfaction rate was ninety-seven percent, and in FY2011, it was ninety-eight percent.[102] The second-most valued metric, volume of projects, also saw a five percent jump, year-to-year.[103] As long as the board’s self-selected metric is not fatally flawed, ALSONY appears not only to be succeeding in fulfilling its mission, but improving on that success.[104] Despite the board’s agreement that these metrics are the best measures of success, however, ALSONY does not use them to set yearly goals. According to the executive director, this is at least partly because (as far as client satisfaction goes), the difference between a ninety-seven percent satisfaction rate and a ninety-eight percent satisfaction rate is more likely due to factors beyond ALSONY’s control than to issues of organizational effectiveness.[105] Still, based on the available data (which is, admittedly, limited by the difficulty of measuring mission success generally) it is hard to argue against a characterization of ALSONY as high performing.

ALSONY has good governance practices in place. It also exhibits, at least under the metrics examined, a high level of mission fulfillment. Despite this, there is clear evidence that many directors at the individual level are not governing fully. In particular, board members appear to allow the executive director to control many aspects of the board, and are not sufficiently involved in evaluating the executive director’s performance and pay. This is not a normative assessment of ALSONY; in fact, the Theory of Optimal Governance described below suggests that this may not matter, or that it may even be preferable. Thus, we return to the questions asked at the end of Part II, with a twist: If nonprofit directors in organizations with good practices in place still do not govern, why does this occur? And if such organizations appear to be fulfilling their mission, do they still need to implement procedures to increase governance, and can they do so without decreasing mission fulfillment effectiveness?

IV. A (Somewhat) New Theory of Nonprofit Governance

A. Flaws in the Conventional View

As stated earlier, the conventional wisdom about best practices, governance, and mission fulfillment is that “an increase in the enforcement of best practices will increase governance, and that increased governance will increase mission fulfillment.” As the above case study shows, there are problems with this line of reasoning. An organization can deploy nearly all of the best practices recommended by the ALI, IRS, and practitioner organizations, and still have major governance failures at the individual director level. Furthermore, such an organization can appear, on the outside, to be well-governed simply because it is performing exceedingly well, in terms of its mission, due to other factors. These factors, however, may not endure absent good governance.

There are thus two major flaws in the conventional view of governance. First, because best practices are not tailored specifically to the governance functions of the board, any increase in adherence to best practices will result in only a diminished increase in governance. Second, governance and mission fulfillment, though related, are separate functions of the board; an increase in governance may or may not increase mission fulfillment.

Some practitioners and scholars have recognized that strict enforcement of best practices, as well as the dual imperatives of governance and mission fulfillment, can lead to both confusion and less governance. For example, Klausner and Small note that in many nonprofit organizations the fundraising role of the board (ostensibly a mission fulfillment function) becomes paramount, and the pure governance responsibilities of the board recede.[106] As a result, only some, if any, directors govern. Others focus on fundraising or programming, sit on the board merely for name recognition, or simply shirk their responsibilities.[107]

B. Director Resource Constraints and the Theory of Optimal Governance

Those advancing the conventional view of the relationship between governance and mission fulfillment implicitly assume that increased enforcement of best practices will prevent directors from serving as directors in name only, otherwise shirking their responsibilities. If all practices are followed properly, the story goes, both governance and mission fulfillment reach acceptable levels transitively. Some have recognized a fundamental constraint on this relationship: director resources. In Failing to Govern, Klausner and Small highlight that a board’s responsibilities extend far beyond the governance function, and note that such other functions may, and often do, eclipse governance both in terms of what the board’s role should be and what it actually is.[108] Encouraged more ardently to fundraise, for example, some board members will find themselves unable to fulfill all of their board duties and with little guidance as to which responsibilities should take precedence.[109]

How, precisely, are director resources limited? A lack of time, information, and nonprofit sector expertise, and the desire to avoid confrontation all limit a director participation in governance.[110] As noted in Part II, directors are generally expected to bring “wealth, wisdom and work” to the table. There is a trade-off between these factors: directors who bring wealth and wisdom to the table are likely to be high performers with restrictions on their time; of course, directors expect that they will have to devote time to the organization if they sit on the board. Thus, each director will have a given amount of time he or she expects to devote to the board.

The amount of time directors actually spend in service to the organization has two dimensions. First, the actual amount of time spent will vary from the expected amount depending on other factors in the director’s life (work, personal life, etc.) outside of organizational control. Second, the actual amount of time must be allocated between the director’s various responsibilities (governance, fundraising, volunteering, advising, etc.); this dimension is subject to the joint control of the organization and the director. The resources (time) that a director devotes specifically to governance functions are a subset of the director’s total resources.

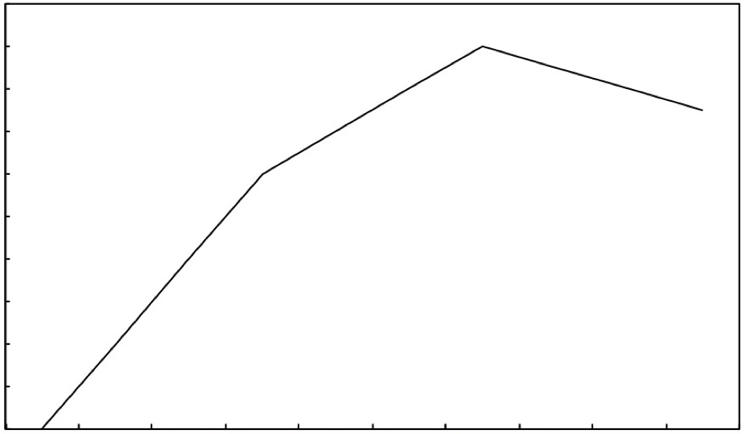

Nonprofit organizations and boards are thus faced with a trade-off between how they use the necessarily limited resources of individual directors. An hour spent reviewing executive pay is an hour not spent fundraising. Given limited director resources, the maximum possible level of director participation in governance can be achieved, but only at the expense of some amount of the organization’s ability to fulfill its mission. Therefore, there must be some optimal level of governance and enforcement that results in the best trade-off for the organization, by providing sufficient governance while allowing the board to help the organization in other ways. This is the theory of optimal governance. The relationship can also be depicted in a graph as a changing linear relationship:

Mission Fulfillment (y-axis) v. Level of Governance (x-axis)

In this depiction, increasing governance (through the implementation and enforcement of governance practices) increases mission fulfillment at a high rate (steep slope), until the board reaches a baseline level of governance (the first inflection point on the graph). At this level, the board provides sufficient oversight to prevent organizational bankruptcy, massive fraud, or other catastrophic negative events. Beyond the baseline level of governance, increasing governance still helps the organization’s mission fulfillment; the board makes sure to balance the budget, engages in meaningful review of the executive director, and otherwise provides good governance. However, once the board reaches the optimal level of governance, additional efforts to enforce governance diverts board members’ limited resources from their most helpful uses to focusing exclusively on governance, resulting in a decrease in the mission fulfillment of the organization.[111]

C. The Bifurcation Solution and Its Flaws

Klausner and Small and other scholars have implicitly acknowledged this relationship between governance, mission fulfillment, and board member resource constraints. The solution, they say, is to concentrate the governance functions of the board in the hands of a subset of board members, thereby liberating the rest of the board to focus on non-governance functions. In Failing to Govern, they cite three possible ways to address this problem, all of which involve altering the structure of the board: the creation of an advisory board, the delegation of governing powers to an executive committee, and the creation of a two-board option whereby one board has governing authority and the other does not—bifurcation.[112] The article describes the problems with the first two options: in the former case, directors will not accept “advisor” status because they want the status of being on “the Board”; in the latter, the executive committee ends up resembling current boards, and a new “super-executive committee” would need to be created—a never-ending spiral of delegation.[113]

Klausner and Small conclude that state nonprofit law should be altered to authorize a split between a board of “governing” directors, who would retain all the legal responsibilities for oversight and organizational direction of current board members, and “non-governing directors” who would “give funds, get funds, advise the executive director and the rest of the board regarding issues on which they have expertise, and [help] the organization maintain relationships with important constituencies.”[114] This strategy, they argue, will “promote effective governance [while] allowing non-governing directors to focus their time and energy on [other] important responsibilities.”[115]

Certainly, the bifurcation structure (and the other structures described in the article) would reduce monitoring costs by shrinking the number of board members who must be held accountable for governance. Bifurcation also allows for the pooling of those board members with the fewest resource constraints (i.e., the time and expertise to reliably and thoroughly participate in governance functions). However, these structural changes do not resolve the underlying problem: that some directors do not govern sufficiently due to conflicting and dynamic demands on their resources.

If the time, attention and ability of directors to govern were held fixed across a given board period, bifurcation might make sense. But nonprofit directors are individuals with busy schedules and shifting demands on their time outside of their role as board members. If the board period is a calendar year, it may be that board members with more time in March have less time in October, but they are still sitting on the “governing board.” Thus, while bifurcation pools high-resource directors at a given point in time into governing roles, it also shrinks the total resources available for governance, potentially preventing the most efficient governance-mission fulfillment trade-off from being reached.

Indeed, bifurcation may be good for shifting low-resource directors or directors not interested in governance out of board roles, or for addressing the conflicting relationship between fundraising capacity and optimal board size, but so are advisory boards and governing executive committees.[116] Bifurcation seeks to (according to its proponents) give governing authority to those directors most likely to govern; but it actually decreases the number of board members available to fulfill governance functions at any given point in time. Board governance will rarely involve all directors governing all the time. Instead, those with the resources to perform governance functions at a given point in time will govern. Bifurcation ignores this reality. If a nonprofit organization wants to improve the ability of its board to govern, it should not shrink the pool of board members with the resources to do so.

V. Recommendations and a Final Thought

A. Incorporating a Resource-Constrained View of Governance to Best Practices

The resource-constrained Theory of Optimal Governance for nonprofits provides practitioners with a more complete framework for thinking about and addressing board governance failures. The discussion below lays out concrete steps that nonprofits can take to incorporate this theory into their practice and improve both the governance and mission fulfillment capabilities of directors.

If the conventional view of nonprofit governance encourages maximum governance, why do more boards not exhibit maximum governance behavior? Resource constraints, as noted above, provide one explanation. Lack of an effective mechanism for sanctioning board members who do not sufficiently participate in governance is another well-recognized problem of board enforcement.[117] The law does not provide adequate sanctions, as it is “almost impossible to win cases involving only inattentive management”—the business judgment rule standard ensures this.[118] Additionally, legal monetary sanctions would create an undesirable deterrent to assuming directorship.[119] Indeed, Klausner and Small’s bifurcated board is directly intended to address the sanctioning problem; under their regime, board members who do not fulfill their governance role are relegated to non-governing director status.[120] However, such relegation is likely to cause the same types of problems as removal from the board or relegation to an “advisory board.”[121] In most cases, organizations should not bifurcate their boards. To the extent that they do, of course, the bifurcation decision should be resource-dependent; directors unable to continuously devote their time and attention to governance function over the course of their term should be relegated to non-governing status.

Eschewing structural changes to boards, several avenues remain for nonprofit boards seeking to improve board member participation in governance:

Make the participation of all directors more transparent. More specifically (and bluntly), engage in public shaming. Group enforcement of individual responsibilities has been wildly successful in other areas, such as microfinance.[122] There is no reason that directors’ performance cannot be shared with the group as a whole. Individuals who join nonprofit boards often value their reputations highly, and sometimes even use board membership as an opportunity to network. Such directors will not want others on the board to view them as shirkers. Accordingly, when the organization, as all nonprofits should, provides an annual assessment of individual board members’ participation (i.e., a “board member report card”), those report cards should be available to all board members. If this practice seems excessively harsh, the organization could also share the results of board assessments in the aggregate, as a way of setting expectations and letting directors know what areas of governance are need greater participation from board members as a group.

Clearly distinguish between responsibilities that relate to governance and those that do not. Board members are faced with many different responsibilities; they have to fundraise, participate in committees, represent the organization at events, apply their expertise when needed, and govern. The distinction between governance responsibilities and other responsibilities is rarely, if ever, highlighted. Many organizations give board members a list of responsibilities when they join that includes both governance and non-governance functions. Board report cards often contain data on an array of issues, from fundraising to committee participation to attendance. These documents should clearly delineate which responsibilities comprise each board member’s legal duty of care; these duties should be highlighted and made paramount.

Build crucial governance activities into the board’s schedule. Other than governance capability itself (which, if the board uses a thorough selection process, should be a given for all board members) the chief constraint on board members’ ability to govern is time. Boards should thus structure governance processes to be efficient. Efficiency, in practice, depends on the composition of the board and other variables too numerous to describe in detail here.

Generally, governance functions, such as evaluating the performance and setting the pay of the CEO, should be central to any annual review. Though these functions may originate in committee, the whole board must make decisions, and perhaps more importantly, the whole board should have detailed discussions. Additionally, the committees involved in these functions should have a flexible membership, such that any director who is available when the committees engage in annual review can be pulled in to both share the workload and provide a fresh perspective.

Incorporation with current reforms. Organizations such as the ALI and BoardSource, and government entities like the IRS and New York Attorney General’s Office should adjust their board governance guidelines and governance practice suggestions to incorporate these reforms. The New York Nonprofit Revitalization Act, signed into law on December 19, 2013, is a step in the right direction, but does not go far enough. As is often the case, lawmakers are far behind innovative practice, and this law only begins to implement some of the basic best practices practitioners have agreed upon for years.[123] However, much power still resides in the rulemaking authority of the New York Attorney General’s Office. To the extent possible, the Attorney General should move to align new rules under the Act with these principles.

Further research. More empirical research needs to be done to understand what governance at baseline-level and optimal-level nonprofit boards looks like. Related research is currently being done by organizations such as BoardSource, which publishes the BoardSource Governance Index, a survey of the nonprofit sector that examines board performance across a variety of areas. Relating such research to the categories implied by the Theory of Optimal Governance would be useful for developing an understanding of where different nonprofit boards lie along the governance axis, and determining how much emphasis should be placed on implementing governance practices and increasing participation in governance.

One of the underlying lessons of the Theory of Optimal Governance is that resource constraints make the trade-off between governance fulfillment and mission fulfillment messy. At different points in the life of an organization, there may be different optimal levels of governance and governance enforcement. If an organization is in crisis mode, for example, the devotion of every director’s full attention to governance may be necessary. Imperfect governance may be not only okay, but desirable at certain points in the nonprofit life cycle because needs in other areas supersede the need for perfect governance. Bifurcation presents a seismic structural shift for the board that, once enacted, would be difficult to reverse due to the alienation of those relegated to non-governing status. But flexibility as to who governs when, and with how much of their time, is crucial to the success of many nonprofits. Rather than trying to separate the governance function of nonprofit boards by limiting those who participate in governance, nonprofits should try to streamline such participation to be as efficient as possible. Recognition of the changing dynamics of governance is essential to improving both governance and mission fulfillment across the nonprofit sector, and making scandals like those at the 92nd Street Y and Met Council fewer and farther between.

On December 19, 2013, the New York Attorney General’s Office announced an agreement under which Met Council agreed to implement a series of best practices to ensure more board oversight and paid half a million dollars in fines. Among other reforms, the organization agreed to “address . . . the general duties of the Board and its committees.”[124] As it develops new rules to ensure better governance in the future, Met Council should recognize not only the legal duties of its board members, but the realities of the resources they possess. Without this understanding, any policies they adopt are sure to be less than optimal.

This article set out to answer two questions about the relationship between best practices and governance:

(1) Why do boards with best practices in place not fulfill all of the responsibilities that governance entails?

(2) Should organizations not governing at the maximum level, but still exhibiting strong indications that they are fulfilling their missions, change?

The Theory of Optimal Governance suggests that no matter what practices an organization has in place, the shifting realities of individual board members’ resource constraints will prevent a maximum level of governance. Further, because best practices are not tailored solely to governance functions, efforts to enforce such practices will result in diminishing returns with respect to governance maximization.

In addition, because mission fulfillment and governance are not directly causal and may even be in tension, boards should temper an allocation of directors’ resources to governance with an understanding of board members’ resource limitations and the other roles through which they provide benefits to the organization.

The Theory of Optimal Governance can provide nonprofit boards of directors with a framework for thinking about these issues. These recommendations provide a starting point for implementing practices that will improve board roles in both governance and mission fulfillment.

1. Greg B. Smith & Daniel Beekman, 92nd St. Y Executive Director Sol Adler Fired After Affair with Assistant Discovered, N.Y. Daily News (July 20, 2013, 12:37 AM), http://www.nydailynews.com/new-york/92nd-st-y-executive-director-fired-due-affair-article‑1.1404191.

2. Greg B. Smith, 92nd Street Y Exec – Once Nabbed in Mafia Stock Fraud – Is Kickback Probe’s Focus, N.Y. Daily News (July 18, 2013, 2:30 AM), http://www.nydailynews.com/new‑york/92nd-street-y-exec-ex-con-focus-kickback-probe-article-1.1401711.

3. Yoav Gonen, Rebecca Rosenberg & Bob Fredericks, Sheldon Silver Pal Faces Theft, Money Laundering Charges, N.Y. Post, Sept. 25, 2013, at 22, available at http://nypost.com/2013/09/24/sheldon-silver-pal-busted-for-theft-money-laundering/.

4. Josh Nathan-Kazis, Jewish Charity Scandals Tied to Long Tenures and Weak Oversight, The Jewish Daily Forward, October 21, 2013, http://forward.com/articles/185814/jewish‑charity-scandals-tied-to-long-tenures-and-w/?p=all.

5. This article does not attempt to provide a one-size-fits-all definition of mission fulfillment. However, it refers to mission fulfillment as the operations of a particular nonprofit to achieve some sort of quantitative or qualitative step towards the organization’s mission statement. For example, if an organization’s goal is to feed as many New Yorkers who cannot buy enough food on their own as possible, each meal provided might constitute one step towards mission fulfillment.

6. See generally William W. Bratton & Michael L. Wachter, Shareholder Primacy’s Corporatist Origins: Adolf Berle and the Modern Corporation, 34 J. Corp. L. 99 (2008).

7. See Melvin A. Eisenberg, Legal Models of Management Structure in the Modern Corporation: Officers, Directors, and Accountants, 63 Calif. L. Rev. 375, 402–03 (1975).

8. Whether this actually happens is a subject of much debate. Compare James B. Stewart, Bad Directors and Why They Aren’t Thrown Out, N.Y. Times, Mar. 29, 2013, at B1, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/30/business/why-bad-directors-arent-thrown-out.html?_r=1, with Brock Romanek, Director Removals: Yes, Shareholder Votes Really Do Matter, TheCorporateCounsel.net (April 22, 2013), http://www.thecorporatecounsel.net/Blog/2013/04/sec-files-initial-brief-in.html.

9. Henry B. Hansmann, The Role of Nonprofit Enterprise, 89 Yale L.J. 835, 838 (1980). Due to the non-distribution constraint, any budget surpluses or other positive net cash flows must be reinvested in the nonprofit in some way, either into the operating budget, new programs, or an endowment fund (in the event of dissolution, unencumbered assets must be transferred to another nonprofit). Id. See also I.R.C. § 501(c)(3) (2012) (stating that a nonprofit corporation may be formed for any lawful purpose).

10. See, e.g., Fidelity Charitable, What Makes an Effective Nonprofit, “Quality and Characteristics Common to Effective Nonprofits,” at *2, available at http://www.fidelitycharitable.org/docs/What-Makes-An-Effective-Nonprofit.pdf.

11. Hansmann, supra note 9, at 846–47.

12. Id. at 847.

13. Id. at 838.

14. Mordecai Lee, Revisiting the Dartmouth Court Decision: Why the US Has Private Nonprofit Agencies Instead of Public Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), Pub. Org. Rev. 7, 114 (2007) (describing the impact of the Supreme Court’s decision in Dartmouth v. Woodward, 17 U.S. 250 (1819)).

15. Id.

16. See generally Lee, supra note 14.

17. Id. at 137–39 (noting that nonprofits and their stakeholders adopt a “don’t tread on me attitude”).

18. See Michael Klausner & Jonathan Small, Failing to Govern? The Disconnect Between Theory and Reality in Nonprofit Boards and How to Fix It, Stan. Soc. Innovation Rev., Spring 2005, at 44–45.

19. For a discussion of agency costs in the corporate context, see generally Michael C. Jensen & William H. Meckling, Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure, 3 J. Fin. Econ. 305 (1976).

20. For a discussion of profit maximization as the sole end of the modern corporation, see generally E. Merrick Dodd, Jr., For Whom Are Corporate Managers Trustees?, 45 Harv. L. Rev. 1145 (1932) and Eisenberg, supra note 7.

21. See Andrew S. Gold, The New Concept of Loyalty in Corporate Law, 43 U.C. Davis L. Rev. 457, 459–62 (2009).

22. See Evelyn Brody, The Board of Nonprofit Organizations: Puzzling Through the Gaps Between Law and Practice, 76 Fordham L. Rev. 521, 521 (2007).

23. See id. Suffice it to say that the duty of loyalty in the nonprofit context mirrors that in the for-profit context, and arises most frequently in the clear cases of the bad actor: self-dealing, usurpation of corporate opportunity. Most certainly, the duty of loyalty is implicated in the recent scandals at the 92nd Street Y and Met Council, but only with respect to the bad actors (i.e., Sol Adler, William Rapfogel). The boards of directors of those organizations would face no legal consequences absent proof of their complicity in the illegal acts.

24. See Klausner & Small, supra note 18, at 43.

25. See Brody, supra note 22, at 535.

26. Id. at 526.

27. Consumer’s Union of U.S., Inc. v. State, 840 N.E.2d 68, 87 (N.Y. 2005).

28. See Katherine O’Regan & Sharon M. Oster, Does the Structure and Composition of the Board Matter? The Case of Nonprofit Organizations, 21 J.L. Econ. & Org. 205, 219 (2005).

29. See id. at 220.

30. Rick Cohen, Explaining the Big Scandals in Jewish Charities: CEOs Too Cozy, Nonprofit Quarterly (Oct. 23, 2013, 2:25 PM), https://nonprofitquarterly.org/policysocial‑context/23118-explaining-the-big-scandals-in-jewish-charities-ceos-too-cozy.html.

31. Id.

32. Id.

33. Sally Goldenberg, City Suspends Millions in Funding to Jewish Poverty Council Following Probe of Ex-CEO, N.Y. Post (Aug. 15, 2013, 10:32 PM), http://nypost.com/2013/08/15/city-suspends-millions-in-funding-to-jewish-poverty-council-following-probe-of-ex-ceo/.

34. Jan Masaoka & Mike Allison, Why Boards Don’t Govern, Grassroots Fundraising J., May/June 2005, at 10, available at http://ncwba.org/wp‑content/uploads/2013/01/whyboardsdontgovern.pdf.

35. This article refers largely to New York law because the subject of the case study is a New York-based nonprofit.

36. See N.Y. Not-for-Profit Corp. Law, Explanatory Memoranda (McKinney 1983). See, e.g., Linda Sugin, Resisting the Corporatization of Nonprofit Governance: Transforming Obedience into Fidelity, 76 Fordham L. Rev. 893, 894 (2007); Denise Ping Lee, The Business Judgment Rule: Should It Protect Nonprofit Directors?, 103 Colum. L. Rev. 925, 925 (2003). Indeed, the appropriateness of the business judgment rule in the for-profit context has also been questioned; however, in the business sphere it has become the fundamental principle of duty of care jurisprudence. For further discussion of the appropriateness of the business judgment rule in the for-profit context, see Robert Sprague & Aaron Lyttle, Shareholder Primacy and the Business Judgment Rule: Arguments for Expanded Corporate Democracy, 16 Stan. J.L. Bus. & Fin. 1 (2010).