Division and Delay: Evaluating the Efficacy and Underuse of the 10(J) Injunction

Introduction

William Baker∞

A major reason for the steady decline in union participation in America is the ineffectiveness of the enforcement mechanisms available under American labor law. One of the major enforcement mechanisms is the 10(j) labor injunction, which has been underutilized for years but has the potential to be an effective deterrent to unfair labor practices. This paper examines two intertwined reasons for the 10(j) injunction’s underutilization, administrative delay and a circuit split that has resulted in competing standards for granting 10(j) injunctions in the district courts. It aggregates and analyzes approximately 10 years of 10(j) injunction activity at the National Labor Relations Board, between 2011 and 2020, concluding on the basis of the available data that the circuit split and the administrative process do, in fact, impact the rates at which 10(j) injunctions are sought and denied in part or in full.

The potential for a major legislative overhaul of labor law in America is low, and the most effective solutions can be found through administrative processes. This paper therefore posits that decentralizing the decision-making process for bringing 10(j) injunctions within the National Labor Relations Board would streamline the clunky administrative process for bringing 10(j) injunctions. The Board also has the power to articulate more cogent standards that would effectuate the purposes of the National Labor Relations Act and the 10(j) injunction.

I. Introduction

The percentage of American workers in labor unions has been in steady decline for decades.1 While deindustrialization and globalization have played a major role in the decline in union density, many academics also point to American labor law as a source of this decline.2 Rampant violations of workers’ rights to organize go unpunished or are insufficiently curtailed.3 Workplace protections are toothless as they are currently enforced, providing little deterrent to employers who fight to prevent their employees from organizing.4 The prospects for legislative change are minimal.5 Declining union density harms all workers,6 and as unions have become more diverse,7 women and people of color are particularly impacted by efforts to discourage unionization.8 This paper will discuss one potential step towards ameliorating this problem, reforming the so-called 10(j) injunction.9 The 10(j) discretionary injunction is a deterrent to labor law violations which is already written into the National Labor Relations Act (“NLRA”) but is plagued by a clunky administrative mechanism and disparate legal standards across the federal circuit courts. Streamlining the process for bringing, and ruling on, this injunction could go a long way towards making American workplaces more conducive environments to labor organizing.

A. The Structure and Purpose of American Labor Protections

The federal law governing labor organizing and collective bargaining is laid out in the NLRA. This regime has changed little since the law was passed in 1935. The stated purposes of the NLRA are threefold: “safeguarding commerce from disruption, increasing workers’ bargaining power (which will also moderate business depressions, and protecting the exercise by workers of full freedom of association.”10 The statute does so by “guaranteeing workers’ right to organize and to engage in concerted activity for mutual aid or protection,” rights set out in Section 7 of the NLRA.11 The NLRA creates an independent federal agency, the National Labor Relations Board (the “NLRB” or the “Board”), to vindicate these rights.12 Two major amendments, both aimed at “restrict[ing] union organizing and bargaining tactics,” were passed in 1947 and 1959. Subsequent efforts to further refine, reform, and modernize the NLRA have all failed.13

Section 8(a) of the NLRA also defines employer behaviors that aim to interfere with workers’ collective rights, such as retaliatory actions against employees exercising their rights in Section 8(a)(1),14discriminating against union members or discouraging membership in a union in Section 8(a)(3),15 or refusal to adhere to a collective bargaining agreement in Section 8(a)(5).16 Violations of Section 8(a) are termed Unfair Labor Practices (“ULPs”).17 Under the NLRA, a worker may file an allegation of a ULP with a Regional Office (headed by a Regional Director), which will investigate the claim and, if appropriate, bring charges against the employer.18 An NLRB Administrative Law Judge (“ALJ”) then presides over an adjudication and will order a remedy, which may be appealed to the federal courts.19 The NLRB may also ask the district court for a discretionary injunction, referred to as a 10(j) injunction because the mechanism is set out in Section 10(j) of the NLRA.20 10(j) gives the NLRB the authority to petition the district court where a ULP is alleged to have occurred for appropriate temporary relief.21

B. The Promise of, and Barriers to, the 10(j) Injunction

The law as it stands offers reinstatement with back pay as the principal remedy for individual unlawful discharge. It does not authorize fines or damages as punitive solutions to the use of corporate force to chill workers’ rights. The NLRA envisions a company’s actions against its employees, even individual employees, as harms that are done to the ability of the body of workers to organize, not as individual harms. These limited remedies, coupled with a slow adjudicative process, “create a huge incentive for employers to deliberately violate…[the] statute knowing that they will reap the benefit of illegal conduct…”22 With little hope of legislative change, those who wish to strengthen the American labor movement have looked to the NLRA for underutilized enforcement mechanisms that could strengthen the NLRB’s power to prevent and remedy unfair labor practices. One such mechanism is the 10(j) injunction, designed to preserve the status quo while the NLRB adjudicates ULP charges.

The 10(j) injunction has long been considered a potential tool to discourage violations of Sections 8(a)(1), (3), and (5) of the NLRA. Virtually unutilized into the 1970’s, the Board, recognizing the potential for providing immediate relief to charging parties during the often-lengthy process of administrative adjudication, steadily expanded its use from that time into the 1990’s.23 Thereafter, despite calls from commentators and Board officials, the 10(j) injunction has never been utilized to its full potential.24 Its use has been politicized through attacks in Congress, which has proven to be an additional barrier to the viability of expanding the use of the injunction.25 The use of the 10(j) injunction came to an “almost complete cessation” during the late Clinton years and under the second Bush Administration.26 Even under the more-active Obama Administration, the 10(j) injunction never returned to its former heights: fifty-nine 10(j) petitions were authorized in 2011, approximately one-third the number at the Clinton-era zenith.27 Under the Biden Administration, Jennifer Abruzzo, General Counsel of the NLRB, issued a memo encouraging regional offices to consider bringing 10(j) injunctions promptly and expanding the class of cases in which the Board will consider pursuing injunctions.28 Memos extolling the virtues of the injunction were also issued during the Obama Administration.29

Professor Charles Morris called the injunction, in 1998 and again in 2019, a potential deterrent to unfair labor practices that was seriously underutilized by successive Boards, comparing 10(j) injunctions to similar, but more widely utilized, systems under the Railway Labor Act.30 Professor Samuel Estreicher similarly asserted in 2010 that “no other remedy under current law would more effectively bring home the central message of the NLRA,” that the choice to engage in organizing activity will not alone jeopardize one’s employment.31 Both authors have urged the NLRB General Counsel to bring 10(j) petitions in every meritorious case of 8(a)(3) discharge, and called on the NLRB to streamline its process for bringing 10(j) petitions to court.

Interim injunctions have the potential to deter ULPs. They diminish the efficacy of attempts by employers to weaken union organizing efforts. Absent an immediate remedy, efforts to weaken union support through intimidation and reprisals against those who organize will succeed. The same is true for refusals to bargain, especially in the first contract setting. “The Board cannot fashion a retroactive remedy for the harm to industrial peace” that occurs as the result of refusals to bargain and unlawful discharges, because the Board has no tools for retroactive awards at its disposal.32 10(j) is intended to act as a tourniquet to stem the bleeding because the Board lacks the ability to repair damage to the bargaining process post facto. An employer can cause irreparable damage to a union organizing drive even if the ultimate disposition of a case is against them. Injunctions requiring the reinstatement of employees terminated during organizing campaigns, or compelling companies to bargain in good faith when they fail to do so, diminish the incentive for employers to engage in unlawful conduct and ensures employee faith in their representatives and the NLRB. When an agency has limited authority to remedy harms, minimizing the immediate impact of attempts to chill union organizing is crucial.

The 10(j) injunction, though essential, faces great challenges in implementation. This is exemplified by the most high-profile labor injunction litigation undertaken by the NLRB in recent years. In a nationwide organizing drive, a number of Starbucks locations have unionized.{{

See Beverly Banks, Starbucks Calls On Judge To Halt ‘Memphis 7’ Rehires, Law 360, August 22, 2022, https://www.law360.com/employment-authority/articles/1523150 (Last visited 8/25/2022) (“The nationwide union drive has resulted in organizing at more than 300 stores and over 200 wins”); see also Law360 Starbucks Unionization Tracker, https://www.law360.com/employment- authority/starbucks-tracker (last visited 2/22/2023).}} Starbucks has opposed this drive, sometimes with legally questionable tactics.33 The NLRB has attempted to enjoin Starbucks to return discharged union organizers to in a number of locations, widely utilizing the 10(j) injunction.34 In Ann Arbor, Michigan, another judge granted a nationwide injunction pursuant to 10(j) against Starbucks, ordering the company not only to rehire a fired organizer but to stop discharging protected employees across the country.35 At the time of the writing of this paper, that order had been withdrawn.36 It was later vacated limited to a single store.37 Nonetheless, the 10(j) injunction is seeing a sudden surge in use in these Starbucks cases.38 A petition for a 10(j) injunction was recently granted in the Western District of Tennessee, reinstating discharged employees in a Memphis shop.39 However, Starbucks appealed that order, and has also committed additional violations of workplace organizing laws in the interim.{{

Beverly Banks, Starbucks Asks 6th Circ. To Undo Memphis 7 Rehire Order, December 13, 2022, https://www.law360.com/employment-authority/articles/1557884 (Last visited 2/22/2023); see also Braden Campbell, NLRB Attys Pan Starbucks’ ‘Hostility’ In Memphis Firing Row, February 15, 2023, https://www.law360.com/employment-authority/articles/1576666 (Last visited 2/22/2023).}} These employees were out of work for months as the litigation surrounding the injunction dragged on, although they have now been reinstated.40

The NLRB’s most powerful tool to prevent corporations from nipping organizing efforts in the bud is hamstrung by such delays because of the NLRB’s minimal power to remedy the damage firings such as these do to union drives.

C. The Solution

This paper will argue that there are two interrelated factors that stand in the way of effective expansion of the use of 10(j) injunctions. The first is administrative delay. NLRB practices, including an “elaborate internal process for handling 10(j) cases,” create significant delays in identifying promising cases and ultimately in bringing meritorious 10(j) petitions to court.41 10(j) injunctions are also both complex and discretionary, creating further barriers to the expansion of their use. Delay causes inherent damage to claims for injunctive relief designed to preserve the status quo.

Second, courts throughout the country apply different standards in adjudicating NLRB claims for injunctive relief. Competing standards for granting 10(j) injunctive relief appear, based on national data, to hamstring the injunction in many circuits. Administrative delay weighs heavily against injunctive relief in some courts. A number of circuits also require heightened evidentiary standards when granting 10(j) injunctions, such as a showing of actual harm or defining the injunction as an extraordinary remedy. These evidentiary burdens regionally impede the successful expansion of the utilization of the 10(j) discretionary injunction.

This paper posits that these two competing barriers, administrative delay and disparate standards, interact. The NLRB is penalized for its delays in requesting 10(j) injunctions from district courts. However, 10(j) injunctions are also granted more frequently when the NLRB takes its time in building its case. This indicates that the NLRB’s cumbersome administrative process and the unrealistic standards of the courts must be addressed in tandem to render the 10(j) injunction a more viable deterrent to violations of the NLRA.

Finally, this paper will argue that the two major barriers to the widespread use of the 10(j) injunction, being interrelated, can be solved with a single solution. Streamlining the process of petitioning the district courts for an injunction by devolving authority to the Regional Directors would serve two purposes. It would allow the petitions to be brought promptly, without the current 10-step process which required the approval of the Board. It would also allow Regional Directors to be more nimble and accurately assess the chances that the NLRB will prevail in any argument for a 10(j) injunction, given the burden of varying evidentiary standards across the circuits. There are other measures, such as taking steps to more effectively define the legal standards for a 10(j) injunction, that would also aid in making this a more widely utilized mechanism in labor law.

II. Delay

The 10(j) injunction is designed to skirt the lengthy process of Board adjudication of ULP and thereby diminish the short-term harms of employer efforts to chill unionism. Yet between 2011 and 2019 the Board, on average, took nearly eight months to go from the filing of a charge to authorizing a petition for a 10(j) injunction.42 This delay, which stems from a clunky administrative process, negates the 10(j) injunction’s potential to preserve the status quo quickly and effectively. Additionally, courts which deny a 10(j) injunction may do so because the petition not timely, so delay also results in the rejection of 10(j) petitions by the district courts.43

The Board currently uses a complicated ten-step process to decide whether to request a 10(j) injunction.44 While much of the process is simply the internal policy of the NLRB, the Board itself (or the General Counsel of the NLRB, if delegated) is the entity empowered by Section 10(j) to bring a labor injunction.45

The Regional Director must complete an investigation and make a determination regarding the merits of the charge as well as the appropriateness of injunctive relief. If injunctive relief is requested, the Regional Director must prepare both an unfair labor practice complaint and a memorandum seeking authorization for injunctive relief to be reviewed by the Injunction Litigation branch within the General Counsel’s office. If the General Counsel agrees that injunctive relief is warranted, he will seek Board authorization for injunctive relief. If the Board concurs and votes in favor of authorization of 10(j), the General Counsel sends the request back to the Region for the drafting and filing of an injunction.46 Two major bottlenecks create excessive delay. The initial investigation of the charge and obtaining evidence in support of the merits may be lengthy, and obtaining additional evidence supporting injunctive relief may also create delays in evaluating the appropriateness of an injunction. The General Counsel and the Board’s considerations also can be lengthy. This cumbersome administrative process effectively destroys one of the most effective elements of the 10(j) injunction.

10(j) injunctions face administrative delays in part because they are discretionary. Mandatory injunctions, like the 10(l) injunctions required for secondary boycott charges, do not face the same types of delay because there is no choice regarding whether to bring such a matter to court once the Region concludes that the charge has merit.47 10(j) injunctions, because they are discretionary, may face delays before the process of building a case for approval by the General Counsel even begins. The NLRB manual for addressing 10(j) injunctions urges Regional Directors to engage in “[e]arly identification” of potentially meritorious petitions.48 Yet because discretion initially lies in the hands of the Regional Director, 10(j) injunctions may not be investigated promptly. 10(j) injunctions in their current form take a long time and have low chances of success, and when a 10(j) injunction petition is going to be brought, Regional Directors want to ensure they have a strong case.49 While charging parties can request 10(j) injunctions to speed the process, experienced parties know that this will prolong and complicate an investigation.50 Moreover, the low chance of success in many circuits may lead the General Counsel to veto many requests for 10(j) relief as unlikely to succeed. The 10(j) injunction thus may be an afterthought, or even discounted completely in some circuits, until it is too late to bring a timely petition.

Finally, delay simply occurs because 10(j) cases are complex.51 Regional Directors may make their cases for 10(j) injunctions to the district courts on the basis of affidavits alone; however, they often choose not to do so and instead collect evidence of the ULP to bring before the court.52 This may be an attempt to increase their chances of success.53 This evidence collection process can be lengthy, and hearings in district court can take time due to the extent of evidence presented.54 For this reason, potential 10(j) cases may also be brought before an ALJ for an expedited unfair labor practice hearing, and only be brought to district court subsequently if resolution has not been reached.55 A hostile party can delay the process of collecting evidence significantly by refusing to submit arguments and evidence and by requesting postponements and continuances in this preliminary hearing, which may be scheduled up to 28 days after the issuance of the complaint.56 While most 10(j) cases settle in the process of, or following, this preliminary hearing, those which do not and are brought to district court for injunction proceedings have stronger evidence of an unfair labor practice in the form of the ALJ’s ruling– at the expense of weeks or months of additional delay.

Delay is destructive, both for the success of individual 10(j) injunctions and for the expansion of their use more generally. About 30% of 10(j) petitions denied in whole or in part in the last decade cited delay as one factor in the court’s decision to deny.57 10(j) injunctions which were brought in eight months or less, the average for such an injunction in the last decade, have been denied because the Board’s delay in action was considered by the court too great.58 It is not merely exceptionally complex, slow, or ill-handled cases 10(j) petitions that run up against failure due to delay; the average petition pushes into the standard of unreasonable delay in some circuits. Any solution to the underutilization of the 10(j) injunction will run up against delay as a barrier, both to its effectiveness in providing parties with timely relief and its potential to result in the denial of meritorious petitions.

III. Standards of the Courts

Another barrier to the utility of 10(j) is the widely varying standards of the courts in granting injunctions. The 10(j) injunction cannot find commonplace use if it is only likely to be used in certain circuits. As noted above, only about 30% of 10(j) injunctions were denied in the past decade in whole or in part due to delay. The majority were denied due to the Board’s failure to show irreparable harm, or when the court balanced the equities between the charging party and the company.59 For this reason, while several other standards (such as a required showing that the need for relief is “extraordinary”) also vary greatly by circuit, the “irreparable harm” prong aptly illustrates variance among the circuits.

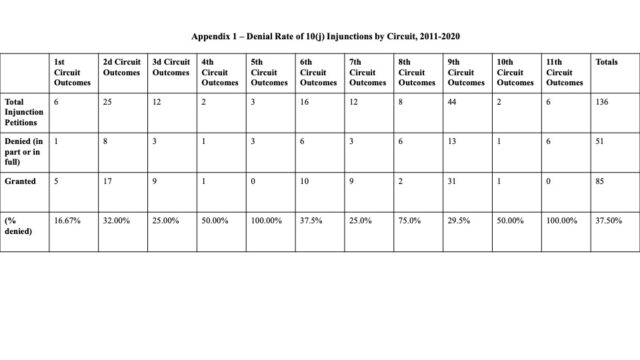

Professor Morris has written that “the final 10(j) results do not appear to differ perceptively based on the particular circuit where the case is tried.”60 That conclusion is incorrect. A survey of all 10(j) cases brought before district courts in the last decade paints a picture of enormously wide variation. Denial rates range from approximately fifteen percent in courts in the First Circuit to one hundred percent in the Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, where the average nationally is just under a forty percent denial rate.61 More than half of requests for 10(j) injunctions are also brought in just two relatively friendly circuits.62 Rather, it might be said that whether a petition for a 10(j) injunction will sink or swim follows the maxim of real estate: location, location, location.63

A. Competing Standards for Granting 10(j) Petitions

There is a circuit split between two competing standards for granting 10(j) injunctive relief, the more deferential Remedial Purpose standard and the traditional Equitable Principles standard.64 The Supreme Court has never ruled specifically on the appropriate standard for a grant of 10(j) injunctive relief. It has required the courts to use the traditional Equitable Principles standard in considering all petitions for injunctive relief unless, “in so many words, or by a necessary and inescapable inference,” legislation bypasses that standard.65 The language of Section 10(j) allows the Board to file a petition for “appropriate temporary relief or restraining order” which the court may grant as “it deems just and proper.”

The Third, Fifth, Sixth, Tenth, and Eleventh Circuits hold that Section 10(j)’s “just and proper” language bypasses equitable principles.66 These circuits consider 10(j) injunctions “different from ordinary injunctions and apply the Remedial Purpose standard.”67 The Remedial Purpose standard defers to the NLRB and limits judicial discretion.68 This standard “requires that a district court find that (1) there is reasonable cause to believe that unfair labor practices have occurred, and that (2) injunctive relief with respect to such practices would be just and proper.”69

The First, Second, Fourth, Seventh, Eighth, and Ninth Circuits disagree, and follow the equitable standard laid out and affirmed by the Supreme Court for general injunctions.70 These circuits consider the 10(j) injunction a limited exception to a federal policy against labor injunctions and treat the NLRB as any other part, without deference.71 This traditional standard “requires a district court to consider (1) whether the moving party has a substantial or strong likelihood of success on the merits; (2) whether the moving party would otherwise suffer irreparable injury; (3) whether the issuance of a preliminary injunction would cause substantial harm to others; and (4) whether a preliminary injunction would serve the public interest.”72

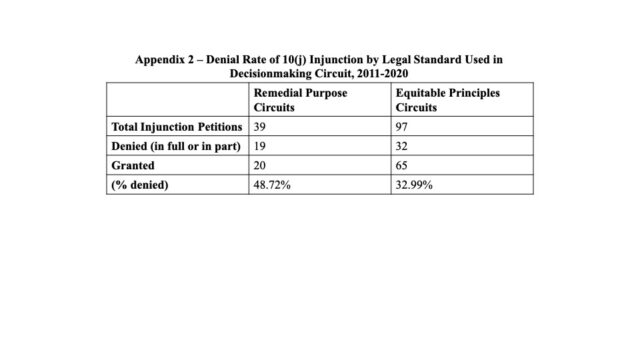

Counterintuitively, injunctions fare worse in circuits which follow the supposedly more deferential standard, with nearly half of injunctions in Remedial Purpose circuits being denied, compared to about thirty percent in circuits applying the Equitable Principles standard.73 It may be that this lower standard “haunt[s] the relationship between the Board and the courts,” damaging the credibility of the Board when it requests 10(j) injunctions under this lowered standard.74 It is also possible that certain courts are hostile to the 10(j) injunction and the NLRB regardless of the legal standard applied.

B. Competing Evidentiary Standards

Disparate success rates for 10(j) petitions may also be attributable to different evidentiary standards that the circuits require.75 Some courts require not merely a showing of irreparable harm, but a de facto showing of actual harm following a potentially illegal discharge or a failure to recognize or bargain with a union.76 This is an impossible standard to meet when the NLRB is merely considering interim relief as it presents an inherent catch-22. If the NLRB waits until support for a union actually dissipates because of a discharge or a failure to bargain, interim relief may no longer be warranted, because the harm an injunction was meant to stem may already have resulted. Delay will already have caused potentially irreparable damage to the union organizing effort and support. If the Board does not wait for such harm, it risks denial for having failed to show that the harm was irreparable.

In such cases, a showing of actual harm is not warranted. While balancing of harms is still important, discharges during an organizing campaign and failures to bargain in first contract negotiations are inherently chilling. The absence of union leadership in the workplace displays a persistent “negative message,” an intended signal by an employer that union activity will be punished, and “the remaining employees are deprived of the leadership of active and vocal union supporters,” inherently weakening union cohesion and effectiveness in the workplace.77 This potential to chill support for a union should also be considered.

This concept is intrinsic in the standard for granting an injunction under the equitable remedy standard, although it is framed many ways. The First Circuit considers the “potential” for irreparable injury when considering 10(j) injunctive relief.78 The Eighth Circuit frames this concept as a “threat” of irreparable injury.81 The Fourth Circuit considers a “likelihood” of irreparable harm.79 Courts must give proper weight to this impending future harm, implicit in every unfair labor practice that can be enjoined via 10(j). If the threat of future harm is measured by, say, a showing that “the Union has not lost any active members,” the courts are not properly weighing the forward-looking nature of the harm the 10(j) injunction is meant to remedy.80 By the time such a showing of future harm could actually be made, the harm would be irreparable and an injunction moot. Because the NLRB’s remedies are exclusively future-facing, and the Board cannot resurrect a damaged union organizing drive or effectively remedy a refusal to bargain, the potential for harm must be taken seriously by the courts.81 In preserving the remedial power of the Board, courts must consider the limitations of the Board’s remedial power and the risks of long-term damage inherent in those limitations.

C. The 10(j) as an Extraordinary Remedy

Several circuits hold that the 10(j) injunction is an “extraordinary remedy.”82 While this is a factor in only about 15% of denials, it represents a near- blanket reason to deny injunctions that has no support in the purpose of 10(j).

Denials for failure to meet an “extraordinary remedy” standard have only occurred in the three most hostile circuits in the past decade: the Fifth, Eighth, and Eleventh. This prong of a court’s evaluation of 10(j) holds that the injunction should only be a remedy in “egregious” cases, and results in a comparison to “similar cases.”83 This presents an obvious problem. When the “extraordinary remedy” is defined only in relation to labor practices as they currently are, it neglects to consider that the average unfair labor practice within the categories considered appropriate to enjoin under 10(j) result in extraordinary harm. Discriminatory discharges during an organizing campaign, the coercion of employees, and refusals to bargain in initial contract negotiations always have at least the potential to stifle the Section 7 rights of workers. The extraordinary remedy standard fails to consider the context in which the unlawful acts occur, and creates a vague moving target. If many employers engage in discriminatory discharges, the practice of firing an employee for union activity, and the goal of diminishing support for a union, ceases to require “extraordinary remedy” because it is no longer an egregious problem. It becomes commonplace.

In one case, the retaliatory discharge of sixteen employees for picketing was not considered extraordinary enough to warrant an injunction because the “speculation” that employees would scatter or that this action would produce a chilling effect did not merit an extraordinary remedy.84 In another case, a 10(j) petition was denied after an employer refused to hire four employees to avoid successorship obligations and interrogated employees as to their union affiliation, the court concluding that the employer’s interrogations were not egregious relative to other interrogation cases and the refusal to hire lacked “overt” threats.85 In a nation where “management hostility to unions and collective bargaining” has become the norm, this standard results in otherwise meritorious cases being denied relief because they are merely discriminatory, or merely chill union support, without going the extra mile of also being heinous, particularly malicious, or unusual.86

Both the “irreparable harm” standard and the “extraordinary remedy” standard result in great geographical variation between the courts. These standards must be made uniform in order to effect a national expansion of the 10(j) injunction, as opposed to an expansion that only reaches certain circuits.

IV. Interaction Between Delay and Standards

The impact of the differing standards for a 10(j) injunction cannot be understood without also considering delay. The impact of delay on the court’s decision to issue an injunction may come in one of two places. On the one hand, a district court may see the long delay as indicative of a lack of irreparable harm or urgency on the part of the Board.87 Alternatively, courts may look to a long delay as having ironically resulted in the harm the injunction should have prevented becoming irreparable, and therefore whatever problem the Board was trying to enjoin has expired as a threat.88 In both cases, delay undercuts the evidence presented to the court justifying the need for injunctive relief.

Delay is thus an evidentiary problem for the Board when it brings petitions for 10(j) injunctions before the courts, and also an independent challenge (as a delay in filing for injunctions harms union organizing efforts and the employees who participate in them).

It should be noted, counterintuitively, that the Board has taken a longer time to file the average successful 10(j) injunction during the past decade than the average unsuccessful or partially successful filing.89 This implies that the evidentiary standards of the courts are typically misaligned with the purpose and undermine the Board’s ability to bring successful 10(j) injunctions. This cuts against the idea that the courts may fail to understand the extent of time or process a 10(j) petition requires, resulting in denials on the grounds of delay. It indicates instead that when the Board puts more time into collecting evidence, waits until actual harm has resulted which it can bring before the court, and vets its petition more thoroughly, the courts are in fact rewarding such delays as stronger cases. For this reason, a mere alteration of the standard of the courts regarding delay seems like the improper route to take in increasing the success of 10(j) injunctions, as the courts appear to reward proper process and only penalize the Board and charging parties when delay compounds already-present issues in a case. Rather, it is the root causes of delay— the Board’s cumbersome decision-making process and the disparate and unrealistic standards of the courts—that must be addressed to make this discretionary injunction a viable deterrent. The Board should prioritize dealing with these cases rapidly to prevent harm to organizing union efforts and coercion of employees, regardless of the standards of the courts in evaluating delay.

V. Solutions

The 10(j) injunction has the potential to be a powerful tool in fighting corporate abuses against employees who act collectively. With a legislative solution seemingly impossible, this underutilized legal mechanism has the capacity to disincentivize ULPs. Both barriers set out in this paper may be ameliorated by changes in Board policy, which would require no legislative input, rendering the 10(j) injunction a more muscular deterrent to efforts to stymie organizing.

D. Decentralizing Decisionmaking

The two intertwined impediments to the expansion of the use of the 10(j) injunction, the patchwork of evidentiary showings and legal standards required by the different circuits and delay, may be cured by a single solution. Such a wide variety of standards is suited to a system in which the Regional Directors might have the sole power to petition for injunction. It is also “hard for Washington to evaluate [the] quality” of 10(j) cases due to their complexity.90 Previous proposals for streamlining the 10(j) process have focused on centralizing this power, through delegation to the General Counsel.91 The Regional Directors, closer to the evidence and the standards of the courts, can be more efficient in applying for injunctive relief in those cases most likely to prevail in their districts.

Devolution of 10(j) authority to the regional level is the logical extension of the current system. Regional Directors already head the fact-finding effort at the outset of 10(j) cases, and they file and litigate petitions in district courts. But Regional Directors cannot be delegated this power directly. Section 3 of the NLRA lays out a limited set of responsibilities that may be statutorily delegated to the Regional Directors, which do not include Section 10 powers. The NLRB could, however, delegate 10(j) decision-making authority to the General Counsel, as it has in the past.92 It could then promulgate a mandatory policy, perhaps through rulemaking, requiring Regional Directors to investigate all cases of 8(a)(1) violation, 8(a)(3) discharge, and applicable 8(a)(5) bargaining and recognitional violations with an eye towards a potential 10(j) injunction, and mandate that the General Counsel give deference to the findings of the Regional Directors. This would sidestep the issue of a Regional Director’s failure to promptly consider 10(j), as consideration would be mandatory, and would also ensure that the politically appointed Board and the policies and proclivities of the General Counsel do not abrogate the deterrent effect of the 10(j) injunction.

A ten-step process would thus become a four-step process: 1) A filing of a case with potential 10(j) implications would automatically trigger collection of evidence from both parties by the Regional Director, 2) the Regional Director would submit that evidence and any findings to the General Counsel for review, 3) the General Counsel would approve or deny the injunctions, as advised, and perhaps send a memo and any advice back down to the Regional Director for 4) immediate filing of a 10(j) injunction at the discretion of the Regional Director. In limiting the actual decision-making surrounding the injunction to a single party and removing any discretion in implementing one of the few affirmative remedies in labor law, many cooks can be removed from the 10(j) injunction kitchen. The NLRB would be able to seek relief for charging parties efficiently, reducing delay while at the same time increasing its flexibility in addressing the variant standards of the circuits.

E. Defining the Standards

Decentralizing and streamlining the 10(j) decision making process would be an efficient solution to the problems of division and delay plaguing these petitions. There are other solutions the Board can consider in the Courts which would also improve the efficacy of the 10(j) injunction.

The Board could seek to articulate, through rulemaking, the evidentiary standards federal courts should be applying when considering a 10(j) injunction petition. A rule stating that a showing of specific harm to a union organizing effort in the case of the discharge of an organizer is unnecessary, and that such cases have inherent harms which must be weighed, would be crucially important in making the use of the 10(j) injunction more widespread and its application more uniform.

“Egregiousness” is another evidentiary standard ripe for a definitional solution. As it currently stands the standard for egregiousness is too high in many circuits. It is also a moving target. The Board should craft a rule that the “extraordinary remedy” standard is met upon a showing of likelihood of harm. Those unfair labor practices that may be enjoined through 10(j) are inherently extraordinary, and this is not a punitive injunction whose penalties should be preserved for only the worst labor violators. The intent of the 10(j) injunction was not to limit the remedy to only the most heinous and drastic instances of employer abuse, but to provide the NLRB with a tool to preserve its remedial power pending the long administrative adjudicatory process. Discriminatory discharges and refusals to recognize and bargain, along with attempts to intimidate employees, are inherently extraordinary because they illegally infringe on employee rights to organize. Because the Board has no remedial power beyond reinstatement and back pay, 10(j) injunctions must be considered, not against the changeable backdrop of American employment norms, but against a fixed understanding that certain ULPs are unacceptable and must be restrained.

While differences in the applicable standards would be more efficiently handled by devolved decision-making, there is a risk that such a system would lead to permissive circuits seeing a flood of injunctions while stingy circuits would cease seeing requests for injunctions at all. This might be a boon for the success rate of 10(j) petitions, but it would also damage the deterrent impact of the injunction and result in geographically disparate protections from discriminatory discharge and other ULPs. A Supreme Court ruling affirming the use of traditional equitable standards in all 10(j) cases, while a lower priority than articulating the standards above, might be effective in streamlining the process of deciding whether to bring 10(j) petitions while increasing the buy-in of courts within the more hostile circuits. Although variation across the circuits may never be eliminated entirely, the extreme hostility of certain circuits to 10(j) injunctions needs to be reduced before this remedy can see more widespread use in the American labor landscape.

VI. Conclusion

There is wide agreement between academia and the NLRB that the 10(j) injunction is a powerful tool that can curb the current epidemic of labor law violations. Administrative delay and high, inconsistent standards across circuits create an environment in which it cannot thrive. While there are many persuasive calls for reforming labor law in America, this paper calls for no comprehensive legislative change. The 10(j) injunction is existing, underutilized, legislation. For this reason, the expansion of its use has the potential to make a difference in the everyday organizing of workers in the short term. Small changes that do not require the buy-in of Congress, in the form of streamlining the administrative process for bringing an injunction, the devolution of decision-making authority, and establishing consistent nationwide standards, can facilitate the 10(j) injunction’s expanded use. These changes have the potential to have an immediate positive impact on unions and workers and should be considered by the NLRB.

Appendices

Suggested Reading

Labor Law and the NLRB: Friend or Foe to Labor and Non-Union Workers?

Wilma B. Liebman{{Former Member and Chairman, National Labor Relations Board, 1997-2011; visiting distinguished scholar Rutgers University School of Management and Labor Relations 2015-17; adjunct faculty, NYU Law School, spring 2015 and 2016. This article is based on remarks at the

Law and the Questions and Answers of Workplace Mobilization

Michael M. Oswalt{{Michael M. Oswalt is an Assistant Professor at Northern Illinois University College of Law.}} Organizing is risky. Some workers join in and get fired, others face intimidation and drop out, while most–sensing the tension between legal rights and

Much Ado about Nothing: NLRB Regulation of Union Affiliation Elections

NLRB's current review policy of union affiliations is flawed and there is a question as to whether it should exist; review intrudes on union internal affairs.

Division and Delay: Evaluating the Efficacy and Underuse of the 10(J) Injunction

"There is wide agreement between academia and the NLRB that the 10(j) injunction is a powerful tool that can curb the current epidemic of labor law violations.”