Prison Scars Due to Cruel and Inadequate Medical Treatment at an Indiana Prison

Introduction

Kenneth Zamarron∞

In 1976, The U.S. Supreme Court in Estelle v. Gamble explained “[an] inmate must rely on prison authorities to treat his medical needs; if authorities fail to do so, those needs will not be met.”1 Kenneth Lee Zamarron unveils his shocking story of medical authorities turning a blind eye to his legitimate medical needs.

United States correctional facilities housed 1,526,800 inmates in 2015. 2 with more than 80% of inmates in both State and Federal prison receiving medical care in 2011 and 2012.3

In 2007 I entered the United States prison warehousing system at the Wabash Valley Correctional Facility located in Carlisle, Indiana. I was sixteen years old when my judge imposed upon me what is commonly called a Methuselah sentence of ninety-seven and one half years, named after the biblical figure who reportedly lived to be 969 years old.

When I entered the prison system, I was like most mixed, colored, urban kids (I am Hispanic and Caucasian) I had met in prison, I was unable to read and write. In a word, I was illiterate.

In 2013, however, that would all change when I noticed what appeared to be little pimples developing on my neck and scalp.

Subsequently, I inarticulately wrote a health care request form which inmates use to notify the medical department of health issues they are experiencing. At that time, the medical providers for inmates in Indiana was Corizon Health, Inc., (Corizon). Unbeknownst to me, Corizon had developed a well-earned reputation for providing cruel and woefully inadequate medical care to prisoners in each state in which it had contracts.4 Corizon, it seemed, had prioritized profits over medical care.

Nevertheless, at that time I could have neither imagined nor anticipated the struggles I would have to endure just to receive basic, standard, and humane medical treatment.

As the years passed, my condition worsened. I wrote numerous health care request forms and grievances to medical staff, correctional officials, and the warden expressing three serious requests: (1) to see a dermatologist for a proper evaluation and new treatment options; (2) to stop being prescribed medication already proven to be ineffective; and (3) to be given an adequate amount of bandages and wraps due to the pimples turning into large cysts that would drain constantly. It should be noted that prisoners are not allowed to possess these types of medical supplies without the approval of the medical department as they are not sold to inmates. As both my physical and psychological health worsened, it became apparent that Corizon was ignoring my requests. I fully understand that I am a prisoner, and as a result, I would not receive five-star treatment, but even basic medical precautions and protocols seemed not to matter once I was placed in handcuffs.

Then, in 2017, Wexford Health Sources, Inc. (Wexford), which is owned by The Bantry Group Corporation, won the bid with the Indiana Department of Correction.5 I was hopeful they would provide me adequate care for my condition, but Wexford was just like Corizon, in that they had a reputation for providing cruel, inhumane, and woefully inadequate medical care to prisoners in each state it had a contract.6 Wexford had also prioritized profits over medical care.

I fell into deep despair and seriously contemplated suicide as a means to end both my physical and mental pain. I feared the fight against the colossal power of multiple goliaths (the medical providers and the Indiana Department of Correction). How could I ever succeed against these high-powered entities, when I did not even possess a stone (the ability to read well) or a sling (the ability to write well)?

I was powerless, unarmed, and helpless. I almost caved into my suicidal ideations. However, I thought of the pain I would bring to my family, whom I had already let down with my incarceration. I thought of my ancestors who were stigmatized and ostracized based on their nationality and the pigment of their skin (they too had received cruel and inhumane treatment). Like them, I would fight for justice (the fight for standard medical care) and fight to be treated like a human being. I would stoically face my goliaths.

I began to formulate a plan: learn to read, learn to write, and learn civil law to the best of my ability. I did this to protect my (and other prisoners) constitutional rights. I sought to become more patient, persistent, and compassionate. What was once burdensome and difficult became demystified. I had a newfound respect for Frederick Douglass’ quote: “once you learn to read, you are forever free.” I would respectfully add an addendum: “once you learn to write, you can fight for your right.” I was free and had the tools to fight for my right to reasonable medical care with meaning, substance, and significance.

I continued to write health care request forms and grievances for my chronic bacterial infections and painful, pus-filled lesions that ruptured and drained daily. An overwhelming majority of the time, Corizon and Wexford ignored my requests for bandages and wraps, forcing me to use old, unsanitary cut-up t-shirts and rags. I even had to resort to using toilet paper as bandages. The dehumanizing treatment I experienced further fueled the burning red flame of justice within me.

Then, after nearly seven years of unremitting suffering, at least eighty health care request forms, numerous grievances, and even the submission of an anatomical drawing of my face and head detailing the wounds and scarring I had sustained as a result of medical malpractice, I finally received a consultation with a dermatologist. Within minutes of my having met the dermatologist, he diagnosed my condition as dissecting cellulitis of the scalp,7 a rare condition, the cause of which is unknown. Due to the repeated, painful, swelling, rupturing, and drainage from my long-untreated dissecting cellulitis, I had serious gruesome scarring, known as keloids, which had developed on my scalp and body. I am lucky just to be alive given the fact that dissecting cellulitis, if left untreated, can lead to sepsis, necrotizing fasciitis, and ultimately, death.8 Because of my diligent efforts, I may be scarred for life, but I am still alive, despite the horrific and unconscionable treatment I received from privately contracted prison medical service providers as a result of their collective philosophy of profits over inmate care.

I can fully appreciate that most people are of the opinion that individuals who are incarcerated are there to be punished, but as Margaret Atwood stated, “oppression involves a failure of the imagination: the failure to imagine the full humanity of other human beings.” I respectfully submit that even those of us who are incarcerated are still human beings and deserving to be treated as such.

On February 18, 2021 Kenneth Lee Zamarron filed a Federal lawsuit, Cause No. :21-cv-00098-JMS-DLP for the delay and denial of adequate medical care in violation9 of the Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. I must admit that I am scared and intimidated as I navigate the Federal Court system and file motions. However, with the assistance of other inmates and with the new ability to read and write, no matter what happens in Court, I will forever have freedom in what I have learned through my scars.

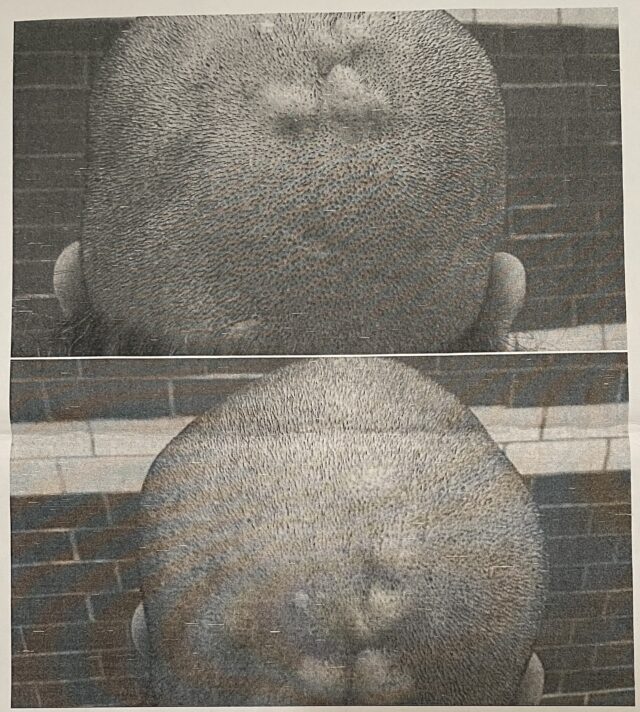

Images of Kenneth Zamarron’s Dissecting Cellulitis

These images may be disturbing to some readers.

[Image ID: Two black and white images stacked vertically of the back of a head with very short hair. The head has five large lumps on the back near the top. The images include the tops of the person’s ears and a small amount of longer hair at the bottom. The top image is from a lower angle and the bottom image shows the top of the head. Behind the head is a black brick wall with a white stripe of brick.]

Suggested Reading

Reporting Behind Walls During COVID

During a time where "social distancing" is a matter of life or death, the overcrowding of our prison systems takes on a whole new light.

Summer of Blood: Voyage Through San Quentin State Prison's COVID-19 Outbreak

There are any number of ways men prepare to survive a prison sentence. If you’re Black, instructions come early in life. How to endure the death-dealing coronavirus wasn’t one of those lessons for me.

Corona Drive-Through

A Washington prisoner gets a glimpse of small-town holiday Americana during the pandemic...

Pandemic Life in Prison: A Plea for Action

As the number of prisoners contracting COVID-19 increases, prison conditions are changing for the worse.